How LUTs Can Elevate Your Cinematography

Let's explain the colour workflow process, what LUTs are, and how they can be used to improve the look of your footage.

INTRODUCTION

If you’ve ever shot something in log and accessed that raw footage straight from the card, you’ll know that it looks extremely flat and visually unappealing. But don’t panic.

This is because that log footage needs to be processed through a specific colour workflow in order to elevate how it looks. Part of this workflow involves using what is called a LUT.

If you’ve at all dived into the YouTube rabbit hole of LUTs, you may have been left a little confused, with the added expectation that I will start trying to sell you my special LUT pack straight after the intro…Don’t worry I won’t.

Instead, I’ll try to provide an overview to clearly explain the colour workflow process, what LUTs are, and how they can be used to improve the look of your footage.

WHAT IS A LUT?

The reason that cinematographers choose to shoot in RAW or with a flat colour profile is that it offers the most colour flexibility in post production, with the widest dynamic range.

Shooting with a colour look already applied or baked into the footage that comes out of the camera leaves minimal room for colour correction to be made or a different look applied to the footage later.

While shooting in a flat colour profile, means that you can later alter the look of the colour and exposure to much a greater degree, manipulate the image and easily make any colour corrections, like changing the white balance, or the exposure without the footage falling apart.

This is all well and good, but what does this have to do with LUTs and what are they?

LUT stands for ‘lookup table’ and is a way of adjusting the colour and tones in an image. The way I like to imagine a LUT in my brain is in terms of layers.

At the bottom layer we have the raw footage that is recorded by the camera. When you download the footage from the card onto a hard drive this is what you will get. As we mentioned, when working with cinema cameras, this is usually recorded in a flat, desaturated colour profile.

A LUT is an extra layer that can be applied on top of the bottom layer. This LUT transforms each pixel’s colour value to give the footage a new look. Different LUTs can be created that output different looks: such as a more standard, natural look, a warm, romantic look, or a look that tries to emulate a film stock.

The reason that I like to think of the raw footage and the LUT as separate layers, is because when using a cinema camera, the LUT is not baked into, or combined with the raw footage. Rather the flat footage is recorded onto the card, while the LUT exists as a separate file that can be applied to the footage or deselected at will.

Because the raw footage is so flat it is difficult to judge things like exposure or colour temperature by using it as a reference on a monitor. To get around this, cinema cameras can apply a LUT as a reference on top of the raw footage that the camera will record, so that the cinematographer can better imagine the final image.

If this same LUT is later applied on top of the flat, recorded footage during the colour grade in software such as Da Vinci Resolve, then the image will look the same as how it was viewed on set with the same reference LUT.

Alternatively, different types of LUTs, other than the reference LUT that was used for exposure on set, can also be chosen and applied on top of the raw footage in the grade.

If there is a colourist, they may choose to either use a LUT as a starting point for the grade and then make additional colour corrections on top of that, or they may prefer to start from scratch and build a new look during the grade.

3 WORKFLOW LEVELS

Before I discuss the way in which LUTs are typically used by filmmakers in the industry on movies, series and TV commercials - I think it’s important to address the common colour workflows that are used across three different budget levels: from solo shooter-level, to mid-level, to industry-level.

Starting at the solo shooter level, such as wedding videographers - many people within this bracket have their own cameras and also edit and grade the footage that they shoot.

Having the ability to completely control how you want the colour in your image to look at this stage is fantastic - as you can deliver the grade exactly as you imagine it.

However, there’s sometimes a bit of a misconception that a LUT is this magical colour-thing that can be downloaded online then thrown on top of your footage like a filter when you’re editing to make your footage ‘cinematic’.

While this sometimes works, the issue with applying a LUT after you’re already shot all the footage comes down to intention and control. What you want to also be doing is using that same LUT that you use in the colour grade to also monitor how your colour and exposure looks as you’re shooting.

That way you will be able to correctly expose and light the footage in a way that suits the LUT, rather than shooting footage, applying a LUT in the edit and then seeing that you’ve underexposed, overexposed, or lit with an undesirable white balance.

You want to shoot the footage to suit the LUT, not grade the footage to suit the LUT.

Once you start shooting more mid-level content, such as for broadcast TV, you may find that although you shoot the footage, that footage will now get handed over to an editor, and sometimes go through an online edit, which will be done quickly and which you often have no input in.

The next time you see the footage after you’ve shot it is usually when it is broadcast. In my experience this can sometimes go OK, and other times go disastrously wrong - especially if the online editor just throws a random LUT over everything.

Therefore, what I’ve started doing, to try and regain control back over the look of what I’ve shot, is to expose with a LUT that I’ve created in Resolve, get it as close as possible to the final look that I want on set, then hand over that same LUT file to the editor to use as the base look. They can then make small colour corrections if necessary - which saves them time and at the same time preserves the look that you want.

Finally, at the high-end industry level, particularly on long form jobs, cinematographers often regain most of that control of the colour back. This is because there is now money to spend on a proper colourist, who can help get the footage to the look that you and the director imagine.

INDUSTRY COLOUR WORKFLOW

Before filmmakers transitioned to using digital cinema cameras, productions were shot, processed and printed on film. It was the job of the cinematographer to choose which film stock worked best for the job and how that film stock should be processed, colour timed and printed at the lab. This all determined the ‘look’ of the footage.

After the digital intermediate and digital cameras were introduced as the norm, some of this control of the colour and ‘look’ of the footage was taken away from cinematographers - especially if they weren’t allowed to participate in the colour grade.

In recent years many cinematographers have tried to regain control of the look by using a workflow with LUTs that treats them more like you would a film stock back in the day - by exposing with the LUT on set rather than plonking a look onto the footage in post production.

That way they can get as close to the final look of what they want while they are shooting. They can do this by getting a colourist to create a custom LUT for the film before shooting begins.

“The process for me in prep is how close can I can get things ready so that when we are shooting we’re delivering the best product. You know, we start talking about colour - a lookup table, a LUT. You know, I believe the future is creating the strongest negative you can on set.” - Andrew Wehde, Cinematographer

Earlier we talked about the idea of a LUT being like an extra layer that’s applied on top to enhance colour, well, there are also a few more nuances to the colour workflow.

Before adding a look or a LUT, the flat files that come straight from the camera need to use colour processing to be converted to the correct colour space. The most common colour space is Rec 709. This adds saturation and contrast so that the colour looks normal or realistic.

In grading software this is often called doing a colour space transform by inputting the colour space of the camera files - such as Arri Log C - and then choosing the output colour space that you want - such as Rec 709.

Now that we have the footage in the correct colour space we can add a LUT layer or a look to the footage. On professional cinema cameras this can be done with either a 3D LUT or what is called a CDL - a colour decision list.

A CDL is basically a way of tweaking the colour on set as you shoot, by doing things like adding a tint, or controlling how much colour is in the shadows, midtones or highlights. This is usually done using live grading tools on a DIT cart.

“For about two years now I’ve been working on on set colour and trying to deliver my on set dailies to be as close to final as possible. So I’m doing a large amount of on set adjustments. I have a panel so that I can do my highlight and shadow control, I can do full individual colour channels for high, medium, low and I have tint adjustments. I‘m basically pushing the CDL as far as possible. The Bear season two, what you see on TV is my delivered CDL. That’s the first time I’ve proven I can do final colour on set with minor adjustments.” - Andrew Wehde, Cinematographer

His DIT can then create proxies using the look he’s created on set, which are used for editing and passed all the way down the post production pipeline - retaining his look.

Other methods I’ve seen cinematographers use, without live grading tools on set, is to either expose with a specific LUT that their DIT will use to create the proxies, or to get their DIT to grade their dailies on set with software like Resolve, before they create proxies with that look.

Sometimes the DIT will carry an iPad which they can export graded stills to that the DP can view, get feedback on and approve on set before the proxies with that look are created.

Whatever method is used, I think it’s good to at least have some idea about the kind of colour look you want to create before you start shooting. I personally really like this new trend of DPs trying their best to maintain as much control over the look of the colour that they can by using a CDL or a LUT - both when exposing the footage on set as well as when finishing it during the grade.

Cinematography Style: Rodrigo Prieto

Let’s dive into how Rodrigo Prieto’s philosophy on image making affects the camera and pick out some of the film gear he uses to create his masterful images.

INTRODUCTION

If you put together a list of some of your favourite working directors of the last two decades, there’s a decent chance that Rodrigo Prieto has shot for one of them: Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Alejandro Iñárritu, Greta Gerwig, Oliver Stone…the list goes on.

Although his cinematography spans decades, it often contains a deliberate use of rich saturated colours, a widescreen aspect ratio and visually bold decisions, which are always focused on presenting a subjective view of the character to the audience.

So, in this episode, let’s dive into how Prieto’s philosophy on image making affects the camera and pick out some of the film gear he uses to create his masterful images.

PHILOSOPHY

“I try to make the cinematography subjective. And that’s in every movie, really, I do. I try to make the audience, as much as possible, be in the perspective of the character. That is not only literally the camera angle being in the POV of a character. It’s more making the camera behave, and the lighting, and everything about it - the texture and the feel of the movie - behave like the main person we’re following.” - Rodrigo Prieto

The idea of creating images that put the viewer into the shoes of the protagonist is one of the underlying philosophies in his work. For example, how do we visually convey a character’s progression from a naive, straight laced graduate to an excessive, risk taking, paranoid white collar criminal.

The camera could start by moving with a smooth, steady motion, under a well exposed light, and later shift to a rough, raw, handheld aesthetic with harder light and stronger shadows.

Or, if we take another story, how do we visually present a series of interweaving timelines and narratives so that the audience doesn’t get too confused?

You could do it by using a different colour cast for each different character arc. Using more sickly, cooler tones for a man in need of medical care, and a much warmer palette for a man trying to hold his life together through his faith.

Or, how do you put the audience in the shoes of a disorientated warrior during a surreal, near death experience during a battle?

How about by radically shifting colour out of the bounds of reality.

You could pick apart each and every one of the film’s he shoots in this way and uncover a philosophical rationale behind the often bold visual decision making that supports the story.

It’s more about creating a feeling and a tone that is representative of a character’s state of mind than it is about shooting from the physical POV or perspective of the protagonist.

Each director he works for brings a different artistic sensibility, however the camera’s subjectivity is always present.

“Every director is completely different. For example, Ang Lee is very precise and also very methodical. And he likes to pick the focal length of the lens. And he talks to me about the framing and composition. He’ll look through a viewfinder and tell me have that corner of that window in frame and this and that, you know. Oliver Stone thrives in chaos. So every time I say, ‘Oliver we have this problem with the camera’, there’s a bump in the dolly, whatever, he’d say ‘Rodrigo Perfect is the enemy of good.’ And Scorsese is maybe a mix of both. He’s very precise in the shot listing he designs and he has a very good idea of the energy he needs the camera to have. But he also leaves space for improvisation by the actors and for new ideas to come.” - Rodrigo Prieto

Being able to adapt to how different directors work is an important skill. Cinematographers should be able to offer both their technical skills and practical advice on how to achieve a desired look or an unconventional shot, as well as lighting each scene.

Some director’s like to maintain more control over how each shot is composed, while other director’s may just describe a tone or feeling that they want to achieve and then leave room for the DP to offer their own ideas and suggestions as to how to achieve that.

When working with directors that like to maintain creative control over small details, it helps to build up a trust in their visual sensibilities and accept the challenge of focusing on the lighting and technical execution of the shots.

Sometimes it may also be necessary to surrender control of minor visual details in order to capture better performances.

“The performances were the essential thing in this film. So, you know, I had to compromise sometimes the possibilities of the lighting to be sure that we captured the performances of these amazing actors.” - Rodrigo Prieto

On The Irishman, this meant embracing the decision to use multiple cameras to cover dialogue scenes - which allowed them to get greater coverage of the performances.

The reason this may compromise cinematic choices is because the more pieces of gear that you place within a set, the more you limit the kind of angles you can shoot, or the space that you can place light without it getting blocked or seen in a shot.

To further complicate things, they had to use an interesting but cumbersome rig that actually accommodated three cinema cameras in order to de-age characters.

GEAR

This 3-D rig consisted of a Red Helium that could shoot high res, 8K files that could later be used for VFX work. This camera was placed in the centre of the rig and captured the actual shot and frame that they would use.

Two, special infrared Alexa Minis were then placed alongside the capture camera as ‘witness cameras’ that also had an infrared ring light to neutralise shadows that could only be picked up by the Minis and wouldn’t show up on the recorded Red image.

They could use these reference clips with the recorded clips and combine it with some AI and machine learning, powered by a NVIDIA GPU chip, to de-age the actors.

Prieto got his camera and grip team to reconfigure this large rig and made it more modular so that the ‘witness cameras’ could be moved around to either be alongside the main camera or at the top and bottom. This allowed them to use this hefty setup on a variety of grip rigs.

Prieto’s photographic decisions are often bold, and use colour expressively. Across his career he has manipulated colour in different ways as the technology has progressed. He’s done it photochemically with film, by using a combination of film and the digital intermediate, as well as with digital cameras and the colour grade.

Let’s compare some of the techniques he’s used - starting with film.

The most common way of shooting on film, is to use a colour negative stock and expose and develop it normally. However Prieto has often experimented with different stocks and development methods.

For example, on Alexander he used the rare Kodak Ektachrome 2443 EIR stock. Sometimes called Aerochrome, it is sensitive to infrared light and displays colour in unusual and often unpredictable ways: turning greens to red, purple or blue. He rated this stock at 125 ISO and used an ND0.3 and a Yellow No. 12 filter to make the effects of infrared light more intense.

Another technique he used in many films, such as Amores Perros, is a type of development called bleach bypass processing. During the processing of film in a lab, the step of bleaching the film is skipped. This results in a black and white layer that is overlayed on top of the colour image, which reduces the saturation of colour, but increases both the contrast and film grain - creating a raw, gritty look.

Instead of doing this technique photochemically on Babel, he did it in the digital intermediate. In other words he processed the film normally, then added a half bleach bypass look to the film in the colour grade.

This allowed him to control the intensity of the look, creating colour that was somewhere in between a bleach bypass and regular development.

As the technology has shifted more towards digital, he’s been able to do everything digitally instead of photochemically: from picking the look of a stock to choosing a development method, all within the grade.

On The Irishman, he chose to differentiate the time periods by applying different film emulation LUTs to both the digital and film footage from different eras: a Kodachrome look for the 50s, an Ektachrome look for the 60s and a bleach bypass development look for the 70s onward.

You can see how foliage looks different across these looks: including deeper shades of blue and stronger contrast in the shadows for the 50s, a bit of a warmer look in the 60s, and a very destaurated but high contrast look from the 70s onward.

He’s used many lenses over the years, but has often reverted to shooting in a widescreen format with anamorphic glass, such as the Hawk V-Lites, the Arri Master Anamorphics or Panavision G-Series.

Prieto also likes using Arri cameras, whether that is the Arricam ST or LT when shooting on film, or on variations of the Alexa when shooting digitally.

Another example of how he uses colour can be found in how he lights night interiors and exteriors. He often uses quite a classic technique of creating alternate planes of colour in different parts of the image. Specifically, he likes to create pockets of warm light indoors and then place cooler, blue sources of light outside of windows. This creates increased colour contrast and more depth in the frame.

CONCLUSION

Although he often paints with lots of colour and quite strong visual techniques, it is always done deliberately. Prieto uses the technical tools at his disposal to craft images that create a mood that mimics that of the main protagonist.

Whether that’s through his use of colour, lighting or camera movement.

The cinematography remains subjective and deliberate in a way that subtly or sometimes not so subtly helps to support the story.

Cinematic Lighting Vs Natural Lighting

In this video I’ll show you two different lighting setups for two different looks and compare how you can get away with using only natural light, or how you can elevate that look a bit more by supplementing natural light in a motivated way.

INTRODUCTION

You may think that cinematography would be all about using a camera. However, the most important part of a cinematographer’s job is actually lighting.

Scenes are lit to: create a look that tonally suits the story, to provide a consistent source of illumination that doesn’t change or effect continuity, and to give the camera enough light to be able to properly expose.

In this video I’ll show you two different lighting setups for two different looks and compare how you can get away with using only natural light, or how you can elevate that look a bit more by supplementing natural light in a motivated way.

MOTIVATED LIGHTING

Lighting can take two forms. It can be more expressionist and exaggerated, to completely elevate the footage out of the real world. Or it can be naturalistic, where, although artificial lights are used, they are used more subtly in a motivated way to keep the story within the bounds of realism.

Today we’ll focus on creating a naturalistic look by using motivated lighting. What exactly is that?

Motivated lighting involves first examining the natural light sources that are present in the space and then placing additional artificial film lights to supplement the natural light.

Or, sometimes, if a source doesn’t exist, cinematographers will create an imaginary motivation for it in their head (outside of the frame of the shot) and then add artificial light using that idea.

There are three things to consider when lighting in this way: the direction of the light, the quality of the light and the colour of the light.

Let’s keep these three factors in mind when we go about creating two different looks: a brighter illuminated high key look and a more shadowy low key look.

HIGH KEY - NATURAL

Let’s start by showing how we can create a high key look - without many shadows on our subject - using only the natural available light.

When only using ambient light in a space, it’s very important to be aware of what the natural light is doing.

I chose to shoot the natural light look at a specific time in the morning where the sun was still low enough in the sky that it would angle in I through the main window in the space. I checked the forecast beforehand and made sure it was a sunny day. Light scouting, weather observation and scheduling is very important when dealing with only natural light.

Next we need to think about direction. In this room the main source of light comes from a large window on the side and a smaller window from the back.

Another important part of natural lighting is how you position the subject. Rather than placing her so that she is directly in front of the window and the light source is totally front on and flat, I’ve positioned her so that she is side lit by the sun coming through the window.

Also, placing the main source of light directly behind the camera is normally not a good idea as it may cast the shadow of the camera onto the subject.

This positioning of the subject means the natural light comes through and creates contrast on one side of the face. Also this little window provides a small backlight which separates her from the background.

Now that direction is sorted we can focus on the quality of the light. I’ve used a muslin curtain to diffuse the intensity of the light, softening any shadows, and reducing the brightness of the illumination outside the window.

When setting the exposure level for a high key look I’ve focused on the illumination of the skin by increasing exposure - in this case with an ND filter - until I’m happy with the level of light on the face. This may mean that the area by the window blows out a little bit - or turns to pure white - which isn’t ideal but we can’t control that. Not without lights anyway.

Finally, the colour of our light is that of the natural sun - which also can’t be changed. One reason I usually don’t turn on any overhead house lights when using natural light is because mixing the colour of artificial warmer ceiling bulbs and natural daylight may throw off how colour is recorded.

So there we go, a high key look using only natural light.

HIGH KEY - CINEMATIC

One reason that DPs use lights to still create a naturalistic look is because of this curtain in the background. It’s a bit blown out. In other words the natural light from outside is much too bright and turns to white, lost information. This is not pleasing to the eye.

So to create a better look I will start by setting the exposure of the camera so that it is balanced to the light in the background by only looking at this window. Now it’s not blowing out, however, it’s much too dark to be a high key look.

So, we need to add light. Let’s start by thinking about direction.

Our strongest source of light is coming from the window - we’ll call this our key. Then some of that lighting from the window is coming inside and bouncing back as a soft ambient source - we’ll call this our fill. Then, finally, ambient light from that little window is hitting the back of her head - we’ll call that our backlight.

Using three light sources in this way is called three point lighting.

Now that we’ve identified where the light is coming from, let’s add film lights that mimic the direction of the natural sources.

With our lights on hand, let’s think about the quality of the light that we want. Because the sunlight coming through the big window is strongest we’ll put our biggest light there - a Nanlite Forza 500B II.

The sunlight coming through the window has been diffused by the curtain and is nice and soft, so we’ll do the same and add a softbox, with a layer of stronger diffusion in front of it to soften it as much as possible. I’ve also added an egg crate grid to it which controls the spread of the light, focusing it more directly on our subject and preventing it from spilling everywhere.

Next, we’ll take our second strongest light, a Forza 60B, and use it to recreate some of the natural ambient fill light. This we’ll also diffuse and make nice and soft by using a lantern. This creates more of a soft spread of light. As you can see here it hits the little plant on the table. This mimics the spread and quality of natural ambient sunlight bouncing off a wall.

Finally I rigged a little tube light on an extended c-stand arm as a backlight. This ever so slightly adds to the feel of the light coming from the back window.

Now, for our third variable: colour. To me, the brightness of high key lighting feels like it would go well with a warm, morning look, so I cranked all the colour temps on my lights to 5,000 Kelvin - which is just a bit warmer than normal sunlight.

The 500B also comes with a cool new feature of being able to adjust the amount of magenta or green tint to the light. So I added a bit of magenta which to my eye helps give a warmth to the skin tones.

And there we have it. A high key look - this time with added artificial lighting that should still feel quite natural.

LOW KEY - NATURAL

Let’s take away those lights and create a new low key look with only natural light.

Rather than being bright like the high key look, low key lighting accentuates shadows and darker tones and usually has an overall higher contrast between areas of light and shadow.

Since we’re not allowed to use any lights we’ll keep the same positioning, quality and colour of light as before. However, we are going to change our overall exposure.

To prevent those window highlights from blowing out like they did for the high key look, we’ll lower the exposure using an ND filter on the front of the lens, until we can still read information on the window and it’s not blown out.

This leaves the frame looking much moodier than before, even though the only change made was in exposure, not in lighting.

This creates plenty of shadows across the frame, which may work as a nice look for some stories, however may be a bit too dark for others.

LOW KEY - CINEMATIC

So, let’s see if we can’t find a middle ground between the very shadowy low key, natural light look and the high key look - by introducing some film lights.

We’ll use almost the same placement for our key light as before. But this time, instead of being more in front of the character, we’ll bring it around a little bit more until it’s right on the edge of the frame and is lighting more from the side.

This will create just a little bit more contrast, as less light will fall on the side of her face nearest to the camera.

We’ll go ahead and turn on the same backlight as before. However, this time, we’ll leave our fill light off.

If you compare the high key lighting shot that uses a fill light and the low key shot without one you’ll see that not illuminating the one side of her face creates a gentle shadow on the side that favours the camera - therefore creating more contrast.

Because I’ve moved the key light around, there is less light that spills on the wall behind her, which also makes it feel like more of a low key look.

On top of this, there is a slight difference in colour. Because the low key look is a bit moodier, I cooled down the colour temperature on my fixtures from 5,000K to 6,000K.

So there we go. A low key look that was achieved with motivated lighting, by simply eliminating the fill.

ADVANTAGES OF USING ARTIFICIAL LIGHT

Four different looks: two created without any lights and two created using artificial sources. Lighting is always subjective and should change depending on the nature of the story you are telling.

This look may be better suited for commercial applications, while this look works for a film with more dramatic content.

But besides the look, what other advantages does using lights provide? Perhaps most importantly using lights creates a consistent look, which will hold up for much longer periods of shooting.

If it takes a couple of hours to shoot a scene using only natural light, the look of the ambience may have completely shifted as clouds came over, or the sun got flagged by a building. This means that the consistency and continuity when cutting to different shots will be off.

Using film lights means that even if the natural light changes, the artificial light should maintain the continuity of the look, which means you will be able to shoot for longer.

Also, relying purely on natural light means you have limited to no control over the look of the image. For this video I could pick a day and a specific time where I knew we would get strong sunlight, but that isn’t always the case. If you need an interior to look warm and sunny, but it rains that day and you don’t have any lights, then there’s not much you can do.

2-Perf vs 3-Perf vs 4-Perf: 35mm Film Formats Explained

By far the most popular film format is 35mm. But what you may not know is that there are then 3 further format choices that need to be made between: 2-perf, 3-perf or 4-perf. But what is a perf and how does it affect both the budget and how the footage looks?

INTRODUCTION

The starting point when it comes to choosing which format to shoot a movie on is between digital and film. If film is selected, by far the most popular film format is 35mm. But what you may not know is that there are then 3 further format choices that need to be made between: 2-perf, 3-perf or 4-perf. But what is a perf and how does it affect both the budget and how the footage looks? Let’s find out.

WHAT ARE PERFS?

The manner in which a piece of 35mm film is exposed is determined by the negative pulldown. This is described in what are called perfs. Perfs stand for perforations and are the little holes that you see in the film that span the length of each individual frame.

These holes align with sprockets, which turn in order to mechanically pass an unspooling roll of film vertically through the camera. The film is exposed when it is hit by light which is let through the lens.

35mm film frames can be shot with either four vertical perfs, 3-perf, or 2-perf. As the width of a 35mm frame is standardised to a size of 24.9mm, the number of perfs only effect the height of the frame that is recorded - with 2-perf capturing the skinniest surface area, and 4-perf capturing the tallest surface area.

Exposing a larger area of film to light is kind of like the digital equivalent of recording at a higher resolution - the larger the area the more clarity and higher fidelity it will be. However, the larger the exposure area, the more film needs to be used and the more you will need to pay for film stock and development. So perfs affect both the cost of shooting as well as the quality or fidelity of the image.

The motion picture camera that is used must be specifically set to record frames with a certain number of perfs by adjusting the speed at which the film runs through the camera as well as the height of the gate that lets through light. Most cameras can record either 4-perf or 3-perf, while only specific cameras can record 2-perf frames.

There are two different steps to the filmmaking pipeline. Capturing images on film with a camera and projecting those images on film by passing light through them.

Image capture can happen on either 4, 3 or 2-perf, however 35mm film projectors are set to work with a 4-perf film print. This means that if you capture film in 2 or 3-perf, you would still need to print the final 35mm projection roll in 4-perf frames.

However, now that digital projection has taken over, it’s possible to capture 35mm in either 2, 3 or 4-perf, scan the film negative and then work with the scan in the same way as a digital file - which can later be sent out to cinemas that use a digital projector or for online distributors to upload the file and stream it digitally.

4-PERF

In the late 1800s and early 1900s when motion picture film technology was undergoing development, 4-perf 35mm film capture and projection emerged as the industry standard. This produced a tall aspect ratio of 1.33:1.

4-perf offers the largest exposure area of 35mm film at 18.7mm tall. Because more surface area is used the film grain will be smaller and the image will be of a higher quality.

This large surface area also allows lots of possibilities for aspect ratios. When shooting Super35 with normal sphercial lenses the frame can be used for taller aspect ratios like 1.33:1 or the top and bottom can be cropped to get widescreen aspect ratios like 1.85:1 or 2.40:1.

Before digital, this crop would have been done by printing the final film to a different ratio with a letterbox, or by using a narrower plate that chopped off the top and bottom of the frame when projecting. Now this can be done by scanning the negative and using software to crop the image.

4-perf can also be used with anamorphic lenses. These lenses squeeze the image by a factor of 2, to around a 1.2:1 aspect ratio, so that it is captured as a tall, compressed film frame. It is then later de-squeezed by a factor of 2 to get it to a widescreen 2.40:1 aspect ratio.

Because this method uses such a large portion of the tall 4-perf frame, anamorphic negatives have a higher fidelity and low amount of grain.

Another advantage of 4-perf is that when shooting Super35, the extra recorded area on the top and bottom of the image, that will be cropped out, can help with VFX work, such as tracking.

A disadvantage of 4-perf is that more film must run through the camera faster, which makes it noisier. This also means that it uses the most film out of the 35mm formats, which means more money must be spent on buying film stock and developing it.

It also means that a 400’ roll of film will only be able to record for a mere 4 minutes and 26 seconds, before a new roll must be reloaded into the camera.

3-PERF

In the 80s, cinematographer Rune Ericson collaborated with Panavision to produce the first 3-perf mechanism for 35mm cinema cameras.

Shooting each frame 3 perforations tall as opposed to 4, produced a less tall frame with a height of 13.9mm and an approximate aspect ratio of 16:9.

When shot with spherical lenses this negative could easily be ever so slightly cropped to get to a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, or more cropped to get to a 2.40:1 aspect ratio.

Because of the lack of height of the frame, 3-perf wasn’t suitable for using 2x anamorphic lenses, as it would require too much of the frame width to be cropped and therefore go against the point of getting a high quality anamorphic image. Therefore, 3-perf is best when used with spherical lenses.

However, it is possible to use the much less common 1.3x anamorphic lenses with 3-perf film, as they squeeze a 16:9 size negative into a widescreen 2.40:1 aspect ratio.

Due to the decrease in recording surface area, grain will be slightly more prominent in the image than when using 4-perf.

The main reasons for shooting 3-perf rather than 4-perf are financial and practical. 3-Perf uses 25% less film - which means a 25% reduction in the cost of both film stock and processing of the film at a lab.

It also means that the camera can record for 33% longer than 4-perf. So a 400’ roll gives a total run time of 5 minutes and 55 seconds before the camera needs to be reloaded. This is practically useful especially when shooting during golden hour or in situations where taking the time to reload a camera might mean missing a shot.

2-PERF

2-Perf, first called Techniscope, gained popularity in the 60s when it was used to shoot lots of Spagetti Westerns. These movies were often done on quite low budgets, yet wanted a wide 2.40:1 aspect ratio to frame the characters in sweeping landscapes.

2-Perf does this by further cutting down on the vertical recording height of the negative, taking it to 9.35mm, creating a native widescreen aspect ratio.

At the same time, this reduction in frame size also equates to a reduction in the amount of film that needs to be used. Since it is about half the height of 4-perf, about 50% can be saved on purchasing film stock and processing film. Therefore 2-perf was a great solution to both save money and create a widescreen aspect ratio.

It also basically doubles the recording time of each roll, allowing you to get 8 minutes and 53 seconds with 400’ of film. This means that it’s possible to either roll for longer takes, or that many more short takes can fit on the roll before needing to reload the camera.

Because it is so skinny and lacks height it’s not possible to use this format with anamorphic lenses - not that you would need to since you get the same aspect ratio by using spherical lenses.

It’s also only really suitable for using this aspect ratio, as getting a taller ratio would require cropping into the image far too much and increase how the film grain looks significantly.

Although it has the same ratio as anamorphic, it has a different look. Because the surface area is much smaller than 4-perf, the grain shows up as much more prominent.

In the modern era where film stocks have become much finer grain and cleaner looking some cinematographers like using 2-perf to deliberately bring out more filmic texture and make the footage feel a bit more gritty.

I’d say 2-perf 35mm is basically a middle ground between a cleaner 4-perf 35mm look and a grainier 16mm gauge stock.

CONCLUSION

How many perfs you choose to shoot on has an effect on a number of factors.

4-Perf records onto a greater surface area, which looks cleaner, with less grain, can be used with both anamorphic lenses, or spherical lenses, and has room to crop to different aspect ratios.

However, this comes at a higher cost, with a camera that makes more noise and very short roll times.

On the other hand 2 and 3-perf, use less of the negative, which makes the image a bit grainier, isn’t compatible with 2x anamorphic lenses, and limits the amount of taller aspect ratios you can choose from. But, it’s much cheaper and the camera can roll for longer.

In this way, the choice of 35mm film format, is another technical decision which filmmakers can make that effects both the look and feeling of the image, as well as providing certain technical limitations and advantages.

What Directors Do Vs What Cinematographers Do

How much of the look of each film is created by the director and how much is the look influenced by the cinematographer?

INTRODUCTION

In modern cinema the authorship of a movie is always attributed to the director. And much of a movie is made up of how the visual information is presented in shots.

However, most directors don’t directly operate a camera, pick out the camera gear or determine how each scene is lit. This is usually overseen by the cinematographer, otherwise called the director of photography.

This begs the question: how much of the look of each film is created by the director and how much is the look influenced by the cinematographer? The answer is…well, it depends.

Some directors like Stanley Kubrick were famous for having a large hand in the cinematography choices - from framing and shot selection all the way to picking out what individual lenses would be used.

While other directors may be far more concerned with working on the script and the performance of the actors, and leave many of the photographic choices up to the DP.

Normally though, the answer is somewhere in between these two extremes.

VISUAL LANGUAGE

In order to determine the authorship of a film’s look, it helps to define all the individual elements and creative choices which go into creating a visual language.

Each frame is due to a compilation of choices. This includes: what shot size is used, how the shot is angled and framed, how the actors are blocked within that frame, the arrangement of the production design and what is placed in front of the camera, the choice of medium and aspect ratio, how the camera moves, the choice of lens, how it is lit, graded, and how each shot is placed next to each other and paced through the editing.

There are no doubt other creative choices that also go into creating a visual language, but these are some of the main ones to think about.

Although some directors and some cinematographers may have a hand in guiding each one of those choices, many of these decisions are controlled more strongly by either the director or the DP.

CREW STRUCTURE

The decision making process on a film set is similar in many ways to how a company operates. It is headed by the director, the CEO, who manages an overall vision and direction, and has to make lots of small decisions quickly to manage the project of making a film.

Below the director are other ‘executives’, who also have a large impact on the film, but who occupy a more specialised role. For example the producer, or CFO, who focuses more on the niche of the finances.

Or the cinematographer, the CTO, who is responsible for overseeing how technology is used to capture the film.

Then there are loads of other department heads that occupy leadership roles that are increasingly specialised: like the production manager, or the focus puller.

This analogy isn’t perfect but you get the idea. So, let’s unpack this a bit further by breaking down what a director does versus what a cinematographer does and which visual decisions each is usually responsible for.

WHAT A DIRECTOR DOES VS. WHAT A DP DOES

Creating shots and shot sizes is hugely important in establishing the look. Typically directors and cinematographers collaborate on this, but I’d say more often than not director’s have a stronger say in this, especially in the more structured world of TV commercials - where each shot is storyboarded ahead of shooting.

On larger Studio series or films where shooting time is quite expensive, many directors will create a storyboard in pre-production, which will be passed on to the DP when they come onboard.

Even on less expensive movies directors often like to use this technique to express their vision, keep to schedule and not overshoot a lot of coverage. For example, the Coen brothers are known for using storyboards and being quite particular about each frame which is shot.

However, other directors, such as Steve McQueen, prefer to work in a more collaborative fashion, coming up with shots with the DP and choosing how they want to cover scenes once they are in the location with the actors.

Choosing whether to move the camera and how to do so is built into this decision about creating shots. Often directors will determine what kind of camera moves they would like to build into the shots, such as a push in, or lateral tracking motion.

The cinematographer will then take those ideas and work out the best way to practically execute those moves: whether that be with a gimbal, a Steadicam, a dolly or handheld on a rickshaw.

In other words taking the overall tonal direction and making it happen practically.

Which lens, particularly which focal length is chosen, has an effect on how the shot looks. This is an area where the cinematographer usually controls this choice more than the director.

However, some directors may like to lean into using particular lenses for a trademark look, for example the Safdies have often used long, telephoto lenses on their films, which helps elevate the tense, voyeuristic tone.

While in other cases the cinematographer may bring a look to the table based on their lens selection, such as Emmanuel Lubezki’s work, which is known for using extremely wide angle lenses close up to characters. He’s used this technique in different films, working for different directors.

Blocking, or how actors are placed or moved within a scene, is a visual component that is also entirely determined by the director in most cases. They will work with the actors and walk through the scene, while the cinematographer watches and thinks about camera placement.

Occasionally DPs may provide suggestions to the director if they think that certain movements or positionings may not work visually - but more often than not they will try to work with whatever blocking the director puts forth.

Another part of the process which is mainly controlled by the director is the production and costume design - which is done in collaboration with the art director and costume designer. When pitching a film or commercial, a director’s treatment will often include direction about the kinds of locations, colour palettes and costume which they envision.

However, some director’s may also be open to collaboration with the cinematographer, particularly when it comes to crafting a colour palette.

The palette can also be influenced by lighting. This is a factor controlled almost entirely by cinematographers, and is probably the biggest stylistic part of the look that they bring to the table.

The easiest way to see this is to look at the work of directors, who have worked with different cinematographers on different projects.

These are all night scenes in films by the same director: Luca Guadagnino. Two of them were shot by cinematographer Yorick Le Saux, which feature toppy lighting, a darker exposure and a more muted, darker palette.

The other two were shot by cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom and feature a more vibrant, earthy palette, a brighter, side key light and hanging practical bulbs in the background.

Or how about these films from Quentin Tarantino. Two were shot by Andrzej Sekuła and are lit with hard light from cooler HMIs through windows. These are cut in the background to have different areas of hard light and shadow.

While the other two were lit by cinematographer Robert Richardson, which have more warmth in the skin tones, and are cooler in the shadows. Both use his table spotlight technique: where he fires a hard light rigged in the ceiling into the table, which then bounces a softer warmer light onto the actor’s faces.

Again, same director, but subtly different looks from different DPs.

However, occasionally directors will communicate a specific lighting style across multiple films to the different DPs that they work with. For example, Terrance Malick’s exclusive use of natural light and emphasis on filming in golden hour.

The choice of medium is one that is probably equally contributed to by directors and cinematographers. By this I mean the choice of whether to shoot digitally or on film, in large format or Super35, with spherical or anamorphic lenses.

These overarching decisions about medium are usually made by the DP and director based on their artistic and practical merits. The further technical nuances of that choice, such as which large format camera to shoot on, or which anamorphic lens to use will then almost always be made by the cinematographer.

Choosing the visual language of how shots are juxtaposed and paced in the edit is almost 100% done by the director and editor. The only input a DP may have in this regard is when they provide guidance about shooting a scene in a very specific way during production - such as using a long take, or shooting with very limited coverage - which leaves the director minimal cutting options in the edit.

Once the final cut enters the grade in post production, on average I’d say the director has slightly more control than the DP. But, not always. Some DPs like to expose and shoot digitally on set with a specially built LUT. This LUT is later used as the basis of the look in the grade.

Some cinematographers also push to always be present in the grade, as how the footage is shaped in post production hugely contributes to how a film looks.

A good example of this is how the Coen brothers work with two different cinematographers: Roger Deakins and Bruno Delbonnel.

Whether working digitally with a LUT, or with film in the DI, Deakins tends to favour a more saturated, vibrant, contrasty, look with warmer skin tones and deeper, darker shadows.

While Delbonnel is known for crafting a specific look in post with his film negative that is lower in saturation, cooler in both the highlights and the shadows, and quite often introduces heavy layers of diffusion on top of the image to give it a more of a dreamy look.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, the creation of the images is a balancing act which is dependent on the input of multiple collaborators - from the director to the DP to the production designer.

Directors tend towards providing more of a conceptual guidance about how a movie looks, while cines generally are more about taking those ideas and visually executing them by working with technical crew and equipment.

A DP working for a good director, shooting a good story, will make their work look better. And as a director you want someone who will help you to enhance and photographically bring your vision to life.

Regardless of who does what, the most important thing is to find great collaborators and be open to at least hearing what ideas they bring to the table.

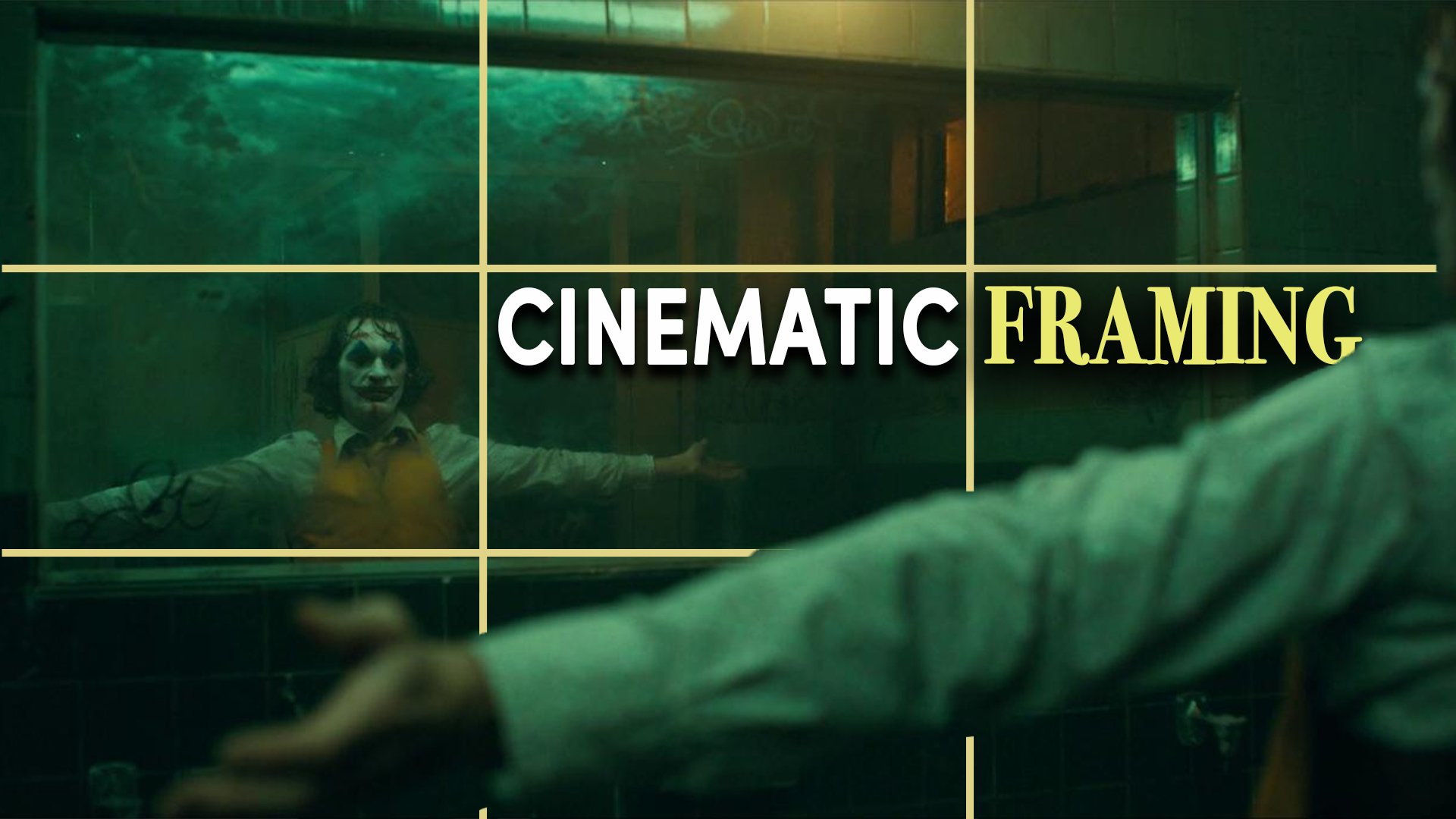

5 Techniques For Framing Cinematic Shots

Filmmakers compose and visually present information within a frame. Let’s go over five different techniques which may help you frame with more of a cinematic eye and tell stories using only images.

INTRODUCTION

Filmmakers compose and visually present each shot within a frame. Frames can be of wide expanses, close up details, symmetrically balanced or even off kilter.

It’s also probably the easiest cinematography skill to practise: as all you need is to be able to snap away on a camera - including the one on the back of your phone. But what is it that makes a good frame?

In this video, let’s go over five different techniques which may help you frame with more of a cinematic eye and tell stories using only images.

1 - USING THE BACKGROUND

What we choose to include or exclude from each shot is a deliberate choice that any image maker should be aware of.

Most shots, whether in cinematography or photography, can be broken down into two components: the subject which the eye is most drawn to and the background, which the subject is placed against.

When filmmakers run through, or block, a scene with actors, one of the factors that they use to decide on the placement of the camera, and therefore the frame, is what background they want to place the subject against.

The background does a few things. First and foremost it’s a way of conveying information within a shot. An isolated, tighter shot of a character against a white wall background includes limited information for the audience. While shooting a character in front of a wider, carefully dressed set with windows reveals several layers of information. This person is sitting in a shabby dressing room, so perhaps he’s a performer.

The highrise building outside suggests that it’s in a city. He’s interacting with another character, but because he is in sharp focus, the camera is suggesting that the man sitting is the main subject in the scene.

For more untraditional, atmospheric filmmakers, who let stories play out slowly without much exposition, how they present each frame is especially important for the audience to glean as much information about the characters and their environment as they can.

A background can either be flat or have depth. This depends on the distance between the subject of the shot in the foreground and the distance to the objects in the background.

Normally, shots which have more depth to them are considered a bit more cinematic - as they create more separation between the foreground and the background and therefore a greater feeling of dimensionality, and more of an illusion of reality.

Like this shot which places a wall of highrises far off in the distance, rendering the looming city with a sense of scope while at the same time isolating the character.

This is also why documentary filmmakers often try to pull their interview subjects away from walls or backgrounds, both to render them more out of focus and to create more depth in the frame.

2 - LENS SELECTION

Each frame is not only affected by the direction in which the camera is pointed, but also by the focal length of the lens that is chosen.

The focal length is the degree of magnification that a lens has and is denoted in millimetres. An easy way to start thinking about focal lengths is by breaking them into three camps: wide angle lenses, medium lenses and telephoto lenses.

There aren’t any official millimetre categories when it comes to grouping focal lengths but I generally think of Super 35, spherical wide angle lenses being somewhere between 16mm and 25mm. With medium focal lengths being around 35mm to 65mm, and telephoto lenses approximately 75mm or longer.

Not only do wide, medium and telephoto lenses provide different levels of magnification, but they also change how the background of a frame is rendered.

The wider the focal length, the more the frame will be distorted and stretched and therefore the more background you will see. Whereas the longer the focal length, the more the frame will be compressed and the less background you will see.

Therefore when framing a close up shot of a subject it’s important to consider whether you want to use a super wide angle lens, with the camera physically closer to the actor, that displays more information in the background.

Or, whether you want to frame using a telephoto lens, with the camera further away from the actor, and show less of the background with a shallow depth of field.

3 - FRAMING GUIDELINES

Although there is technically no right and wrong when it comes to framing, there are a few aesthetic and cinematic conventions or guidelines which have been widely adopted in filmmaking over the years.

One of the foundational framing guidelines is called the rule of thirds. This principle suggests dividing the frame into nine segments made up of two evenly spaced vertical lines and 2 evenly spaced horizontal lines.

You then place the most visually strong elements in the frame, like the subject along these lines, or at the intersection of these lines.

Probably the easiest example to show this is by framing the horizon. Usually cinematographers will either frame a landscape so that the sky portion occupies the top third of the frame and the earth portion occupies the bottom two thirds, or they will flip it and place the earth portion on the bottom third and the sky on the top two thirds.

Another convention is the idea of leading lines. These are where objects in a frame are lined up compositionally so that they create an invisible path which guide’s the audience’s gaze towards a specific part of the frame.

These lines can be created in symmetrical frames by finding elements that lead to a centralised point, like a doorway where a character is standing.

Filmmakers can also create a frame within a frame by composing the subject within a shape, like a mirror, a door or a window to create a more formal perspective.

4 - SHOT SIZE & ANGLE

One of the most important decisions there is when it comes to framing is deciding how wide or tight you want your shot to be.

As we hinted at earlier, wider shots are great at establishing the environment around characters and familiarising the audience with the geography of the film’s world.

While tighter shots, where the subject occupies a large area within the frame, can be used to punch in and highlight details: whether those are an important object in the story or to better read and empathise with the emotion on someone’s face.

I’ve made a whole video on shot sizes before, which I’ll link below, but I think the biggest take away from it is the idea that, in life, our proximity to a person defines our emotional relationship to them.

Therefore, the tighter we frame a shot on a character, the more intimate it feels, while wider compositions feel more emotionally neutral and observational.

At the same time, the angle at which we point the camera at a subject also has a large effect on how frames can be perceived by audiences.

Most shots in filmmaking are taken from a neutral, or medium angle, where the camera is positioned roughly at the eye level height of a character without any significant vertical tilt.

This approximates the viewer’s own eye level and creates a level of empathy and identification with characters. It also conveys a sense of normalcy and realism as it’s not visually jarring.

Low angles, where the camera is positioned at a height below the character's eye line and angled upward, creates more of an uneven emotional connection, which is often used to make characters feel more powerful, physically larger, dominant, imposing and stronger.

While high angles, shot from a tall position with the camera tilted down, tend to have the inverse effect of creating a sense of vulnerability, diminished size or weakness.

5 - BALANCE

Shots that are thought of as cinematic generally have a degree of balance to them. However, this balance can also be deliberately thrown off and subverted for effect.

A balanced frame is one where no part of the image has an overwhelming visual weight from elements that throws off other areas.

One way to think about this is in terms of negative space, empty areas in the frame without significant visual elements, and positive space, parts of the frame that draw the eye towards a focal point.

Filmmakers can create a symmetrical balance by centrally framing a subject and then equally weighting areas of negative space against the middle area of positive space.

Or they can frame shots with asymmetrical balance by placing the main subject in the image off-centre and then weighting the other side of the image with elements of negative space.

Other visual aspects like colour or areas of light and shadow can also be layered to either achieve symmetrical or asymmetrical balance within a shot.

When it comes to framing a dialogue scene between two characters, a common technique is to use a tik-tok or shot-reverse-shot: where each shot is taken from the same side of a 180 degree circle, in a way that may place the characters on opposite sides of the frame.

This introduces another two framing concepts: breathing room and headroom.

Breathing room is the amount of negative space between the subject and the edge of the frame. Traditionally this space is left open in front of characters to give a sense of normalcy. Unless filmmakers want to deliberately introduce a bit more uncertainty or tension by leaving characters with limited or no breathing space.

Headroom is the amount of space above a subject's head. This can either be traditionally framed so that there is some negative space above the character, or the subjects can be given a haircut, so that they have no headroom and the top of their scalp is framed out - which may make the shot feel a bit tighter, more intimate and even tense.

CONCLUSION

There’s no magic tool that will allow you to create perfectly cinematic frames. Probably because there’s not really such a thing as a perfectly cinematic frame. Some movies may need uglier, off kilter shots, while others may benefit from a more precise, symmetrical form.

It always comes down to forming a perspective on a story that you then translate into a look. Every brain will do this differently and interpret how the world is framed in different ways. But hopefully the next time you are practising snapping photos or composing your next shot, you will have some of these techniques in the back of your mind that you can use to manipulate how you want your images to look.

Cinematography Style: Shabier Kirchner

This video will unpack Shabier Kirchner's work as a cinematographer a bit further by going over how he got his start in the industry, looking at some of his thoughts and philosophies on filmmaking and breaking down some of the gear he’s used to create images.

INTRODUCTION

After getting his first big breakthrough working with director Steve McQueen, Shabier Kirchner has emerged as a prominent, self-taught cinematographer in the world of festival and indie films.

His photography mixes expressive but not heavy handed lighting, different formats, big close ups, handheld movement and naturalism to create an often dense, grainy, filmic look that evokes unconscious feelings from the audience.

This video will unpack his work as a cinematographer a bit further by going over how he got his start in the industry, looking at some of his thoughts and philosophies on filmmaking and breaking down some of the gear he’s used to create images.

BACKGROUND

“Images were always something that I was surrounded by. I was just immediately attracted to drawing and eventually photography as a way of expressing how I was feeling. In a way that I couldn’t really do with words or I couldn’t do with writing.”

Although the Antiguan born cinematographer struggled a bit in school, he developed an early love of photography. This was amplified by his dad who also loved photography, so much so that he had his own darkroom.

Here, Kirchner got to experiment with film and learn the basics of exposure and development. As he got older he began shooting a lot of what he was surrounded by, such as surfing and skateboarding. He slowly built a reel, which he would later use to apply to study a Masters in cinematography at the NFTS film school in London.

After making it to the final round of selection, he wasn’t selected. On his way from a job he landed in New York, where he managed to work as a trainee on a movie. The DP on that movie, Thomas Scott Stanton, immediately landed him the amazing opportunity to shoot 2nd Unit cinematography.

After that he settled in New York, working on commercials, music videos, short films and indie projects for the next eight years.

One day he got an unexpected call from Sean Bobbitt, Steve McQueen’s regular cinematographer. Since Bobbitt sometimes worked with NFTS, he assumed it was in regard to his earlier application to the film school, however, it was something far better.

He was looking to introduce a new cinematographer to Steve McQueen, as Bobbitt would be unavailable to shoot an upcoming series he was working on called Small Axe. This sparked another opportunity in his career.

PHILOSOPHY

By breaking down the choices that cinematographers make, my videos may make it seem like cinematography is a very analytical process. But often it’s not at all. Many DPs internalise their years of practice and formal and technical training, then use that to unconsciously make decisions which dictate the visual language of a film based on what feels best.

“Like, everything about this project I felt was done on a very unconscious level. It’s something that now looking back on it I feel that there is a lot of value to operating on your impulses and operating on your emotions. Things that you feel that you may not be able to quite put into words.”

This doesn’t mean that he doesn’t prepare. Depending on the project he may put together a collection of images from photographers that he likes, or conduct research through conversations with the relevant people or communities that the story takes place in. While at the same time shaping a perspective based on his own experiences.

And, of course, he may put together a shotlist. For example, during prep on the first episode of Small Axe, he compiled comprehensive lists of shots for covering scenes - with as many as three different alternatives per shot.

The director, McQueen, dismissed this approach, preferring to work off conversations about the story and characters, which ultimately led them to finding the right visual approach for each episode in the series.

Kirchner also drew from the wall full of period reference photos that the production designer had gathered. This gave everyone a sense of direction of the look, which also fed into his spirit for open collaboration with the crew.

“I want everybody to have read the material. I want everybody to feel what it is that we’re trying to achieve. That, you know, everybody had agency. I think that’s a really important thing. And when you feel that happening throughout a whole crew, the reverberation of that is, like, intoxicating.”

This collaborative environment that he encourages also extends to some of the gear decisions that are made by his technical crew.

GEAR

Fostering an environment on set where everyone, including the technical crew, is on the same page about the look helped when it came to selecting gear and designing lighting setups.

“I wouldn’t call myself the most technical of people and I’m, like, totally OK with that because I have so much trust in people like Ian and his crew. To go and be able to describe a feeling or describe an aesthetic or a quality of light and have someone like Ian take that and interpret it in a way that is achievable is really great. Here’s a photograph, you know, Eggleston took at night and this is the light and it looks like we’re underwater. What do you think?”

This led to a member of the lighting team proposing to the gaffer that they use ETC Source Four fixtures to create different pools of overhead light. These spotlights, often used in stage lighting, can be used to create crisp beams of light that can be spotted. This means that the spread of light can be controlled and dimmed.

They were also easy enough to rig, as top down lamps, from the highest windows of the street facing apartments.

They were all gelled blue-green to mimic the silver allied Mercury vapour lights of that era, to create multiple, controllable top down pools of bluish light reminiscent of Kirchner’s reference photo.

When lighting, he often uses contrasting colour temperatures and fixtures, to create different pops of colour across the frame.

For example, in this interior he used super thin LED Lightmats which could be velcroed to the ceiling, diffused with an off-colour fabric and gelled with leaf-green, steel-green or yellow in different areas to break up the modern, perfect feel of LED light.

This overhead ambience lifted the light levels of the entire space, which was further accentuated by practical tungsten wall sconces to create a warm look. This warm interior light was offset by the cooler Source Four street lights that were rigged outside.

Even for more traditional day interior scenes, which are often lit through windows with stronger, daylight balanced HMIs, he may add little pops of tungsten practicals in the background to contrast the cooler daylight feel with a homely warmth.

“I have so much love for celluloid. I just think that there is something very special to it. The way it treats skin. But I also think that the process in which we work with film, as well. There’s a lot of value in that. To be able to think, like, in an economical way and not just sort of spin the camera and roll and roll and roll. To, sort of, really trust what you’re doing as well.”

When it comes to choosing a medium, he does love the look of shooting on film, but will also choose digital cameras like the Alexa Mini or a Sony Venice, depending on his practical needs or the needs of the story.

A great example is the five part series Small Axe. Each episode was shot on a different medium. He used the cleaner, wider perspective of the large format digital Sony Venice for one, the digital Super 35 Alexa Mini for another episode for its ability to roll for long takes up to 45 minutes.

With grainier, 16mm film used to bring out a 1970s aesthetic, the textural, widescreen 2-perf 35mm film look to frame wider aspect ratio shots of a community, and the more stabilised, structured, taller aspect ratio in 3-perf 35mm for another episode.

Each choice of format brought a different look that better suited the story of each episode.

When shooting on film he used 500T stock from Kodak, 5219 for 35mm and 7219 for 16mm. This stock has a beautiful, higher textural grain to it, and - being rated at 500 ASA - is fast enough to practically use it for both day and night scenes. He’s even push processed this film at times to create even more grain.

Kirchner shoots this tungsten balanced film without using any correction filters - even when shooting in daylight. Prefering to correct the colour temperature in the grade, rather than in camera.

Like his choice of formats, how he chooses lenses is also dependent on the kind of look for the story that he is after. For example, he’s used the Cooke Speed Panchro 2s for their soft vintage roll off and warmth, the PVintage range from Panavison for their smooth, fast aperture, romantic look, and the Zeiss Master Primes for their modern, cooler, sharper rendering of detail which helped capture 16mm with a higher fidelity look.

Although the type of camera movement he uses does depend on the director and the story they’re telling, his camera motion often has a rougher, handmade feeling to it.

Whether through his regular use of handheld, or even by choosing not to stabilise bumps by using software in post production.

Instead, embracing the little imperfections that come from a human operated crane movement in a sweeping shot across a courtroom.

CONCLUSION

“I took some wild chances on things that I didn’t really believe that I could do but I just did it anyway and I failed terribly. But if I could go back again and do it all again I’d do it the exact same way because failing is success. I’ve learnt the most from things that I didn’t succeed at 100%.”

Grip Rigs For Cinematic Camera Movement (Part 2)

To move a cinema camera in different ways requires different types of mechanical rigs. In this video let’s go over some of the common, interesting and even unusual rigs that are used in the film industry to create motion.

INTRODUCTION

There are many reasons to move the camera in filmmaking. It can be used to reveal more of a space and establish the geography of a scene. It can elevate action in fight sequences. Evoke an emotion or a tone. Or even provide an unusual perspective to a scene.

To move a cinema camera in different ways requires different types of mechanical rigs. In this video let’s go over some of the common, interesting and even unusual rigs that are used in the film industry to create motion.

BOLT

The Bolt is a specialised robotic arm rig, which is designed to move the camera at extremely high speeds, extremely precisely. It is built by Mark Roberts Motion Control and is the go to robotic arm for industry level film work.

So, how does it work? This cinebot has a 6-axis robotic arm - which means it has 6 different points where the arm can swivel, rotate, pan, tilt and roll the camera. This arm is attached to a heavy base which is designed to slide along a track - which come in 3 metre length pieces - giving it an additional lateral movement axis.

This total of 7-axes of movement means that it can move the camera in very complex ways, almost anywhere within a confined area. What makes the Bolt special is that it comes with software called Flair that is used to program each move that it makes, frame by frame.

Once a move is programmed it can be saved and repeated as many times as necessary in frame perfect passes. In other words it can perform the exact same motion multiple times, so that each move records exactly the same image, even when broken down frame for frame.

This allows filmmakers to record multiple plate shots of the same take - where they can record different details in different parts of the frame multiple times, then layer different sections of each plate on top of each other in post production.

For example, this is a shot from a commercial that I camera assisted on a few years ago. The Bolt could be used to record two passes. One plate shot of the boy drinking orange juice, and another plate with a dog being cued to jump by an animal wrangler.

In post, the animal wrangler could be cropped out and the motion of the dog jumping overlayed on top of the shot of the boy, so that it looked like it was recorded in a single take. This is made easy by the Bolt’s frame perfect, repeatable, programmed camera moves.

The Bolt is often combined with a high frame rate camera, like a Phantom, to shoot slow motion because the Bolt can move at extremely high speeds. When shooting slow motion, everything, including camera motion, gets slowed down. This means that to shoot extreme slow mo and still get a normal tracking movement, the camera needs to move at a much faster speed than normal.

It can also be used to get super fast camera motion when shooting with the camera at a normal frame rate.

It’s actually a bit scary how fast this heavy chunk of metal can move. That’s why the Bolt operators will usually either cordon off the area that the arm moves in or give a stern warning to cast and crew not to go anywhere near the arm, unless the operators give permission. Because if this thing were to hit anything at a high speed it’d be super dangerous if not fatal.

For this reason, camera assistants will usually strip the camera of a monitor, mattebox, eyepiece and any additional weight that could offset balance or upset smooth movement or even pieces that could fly off while the arm moves and stops at extreme speeds.

Another use case for the Bolt is to program it to do very specific, macro moves. Using the Flair software and a special focus motor, the focus distance can also be programmed for each frame - since pulling focus at these extreme speeds manually is very difficult, if not impossible.

This means it can repeat moves in macro shots, get multiple plates, all while maintaining perfect preprogrammed focus.

Although you can do incredible things with the Bolt, it’s usually reserved for specialised, pre-planned shots only, as it's both an expensive toy to rent and because moving it around and programming it takes a lot of time to do.

TOWERCAM

Another piece of equipment which is designed for a very niche type of camera movement is the Towercam. This is a telescoping camera column which is designed to get completely vertical, booming camera motion. It is remote controlled by an operator near the base of the rig.

Unlike a Technocrane, which is more of an angled telescoping arm, the Towercam is an arm that moves completely vertically and can either be rigged from the ground or rigged from above and telescope up and down.

Although the hydraulic arm of a dolly can also be used to do vertical up and down moves, the range of its arm is much more limited to around 1 metre of vertical boom movement. There are different versions of the Towercam, but the XL can extend the height of the camera to almost 10 metres.

This is a great tool for getting large, symmetrical, up and down moves - which is why Robert Yeoman often uses it when shooting with Wes Anderson, who loves himself some symmetry. Using a dolly for horizontal tracking moves and a Towercam for vertical tracking moves.

But, it can also be rigged with a remote head, which allows an operator on the ground to pan and tilt the camera while it moves vertically. Which is great for this kind of a shot of tracking an actor walking up a flight of spiralling stairs.

It can also be used for doing fast vertical moves, capturing live events, nature documentaries, or any other application where straight, vertical motion is required.

3-AXIS GIMBAL