How Ryan Coogler Shoots A Film At 3 Budget Levels

Ryan Coogler’s career has seen a progression all the way from making a low budget indie movie that became a festival smash, Fruitvale Station, to directing one of the biggest blockbuster Marvel films in the world - Black Panther. Let's take a deeper look at his career as a filmmaker.

INTRODUCTION

“Making a film is something that involves a lot of technicalities, you know. And it is hard work. And it is something that’s systematic to me that I’ve learned. Going up against time and money you know you never have enough of either one when making a film and I hear it’s still like that on films of higher budgets.” - Ryan Coogler

Ryan Coogler’s career has seen a progression all the way from shooting a low budget indie movie that became a festival smash, to directing one of the biggest blockbuster Marvel films in the world.

As you may have seen in this series, directing films at different budget levels has an inevitable impact on how movies are made. Despite this, Coogler’s work is all bound by characters and stories told through an empathetic lens, made by a close knit team of collaborators, which are thoroughly researched and to a large extent shaped by how he writes his screenplays.

So, let’s take a look at the low budget Fruitvale Station, the mid budget Creed and the high budget Black Panther to see how his approach to making movies has evolved over time and identify some commonalities that are present throughout his career.

FRUITVALE STATION - $900,000

“The biggest thing that I walked away with from film school is just a lot of my colleagues. You know, like, I met the composer that’s done all of my films at film school. One of my editors has worked with me the whole time. The community was the most valuable thing that it gave.” - Ryan Coogler

Coogler first became interested in screenwriting during a college creative writing course, where his teacher recognised his talent for his visual writing style and proposed he try writing screenplays.

After undergrad he got into film school at USC where he made a number of short films that did well at festivals with some collaborators who he would continue to work with through his career.

During his studies he mentioned to a friend who was studying law about potentially making a film about the Oscar Grant case. Later, when his friend began working on the case, he introduced Coogler to the Grant family who gave the rights to tell the story.

After the festival success of his shorts, and getting the script for Fruitvale Station into the Sundance Screenwriters lab in 2012, Forest Whitaker came on board to produce through his production company Significant Productions. A production budget of $900,000 was secured to make the film.

“Being in the Bay area at the time and being the same age as the guys who were involved and seeing myself and a lot of my friends in them. Then shortly after seeing it become politicised. Seeing his humanity get split in two different directions. And the fact that he was a human being whose life was lost kinda got glossed over. You know, ,my outlet, my artistic outlet is filmmaking, so, oftentimes, when I see things or think about things I think of them in that format.” - Ryan Coogler

He compiled as much research as he could from a combination of legal documents as well as talking to the friends and family of Oscar Grant. His goal was to treat the story with a sensitivity by humanising the characters on screen through portraying an intimate, personal portrait of their relationships.

Letting the story play out in a world which was as true to life as he could make it. To create this visual world encompassed in realism he turned to a close collaborator, cinematographer Rachel Morrison.

“Fruitvale’s a really interesting scenario for a cinematographer because you have tons of films that are based on true stories but very few that are based on true stories that happened three years ago in locations that still exist exactly as they were. So it’s not this interpretation of something. It was really important to be really, really authentic.” - Rachel Morrison, Cinematographer

She pushed this idea of authenticity visually by shooting on a grainier, more organic Super 16mm film, using a handheld, exploratory single camera and by keeping the lighting as naturalistic, motivated and as true to life as possible.

The smaller gauge film size meant that they shot on wider lenses and therefore had a deeper depth of field than a 35mm film plane.

Morrison shot the film on an Arriflex 416 with Zeiss Ultra 16 lenses which were donated to the production by Arri. The Ultra 16s are probably the sharpest Super 16 primes on the market and since there were going to be a lot of low light scenes, Morrison wanted lenses that would be as sharp as possible when shot wide open at T/1.3 on the lower fidelity 16mm Kodak 500T film.

An idea that the cinematographer discussed with Coogler was finding a middle ground between a deconstructed documentary realism and a fictional, elevated cinematic gravitas - where visual tweaks were made to elevate the story.

An example of this was how they used the colour grade in post production as a low budget way of changing the colour balance of the lights in the real shooting location.

“In the BART station the fluorescent lights up above, actually they’re warm light - which is sort of a yellow, warm feeling to them. And it’s this terrible, terrible event and for me I always, the second I saw them I’m like, ‘Well we’re going to time it cool right?’ And then we got into this dialogue about will it still feel like the BART station if we time it to feel a little cooler instead of being warm. That was the dialogue which was so interesting. Most films I think are much less beat for beat interpretations of things.” - Rachel Morrison, Cinematographer

By shooting with no large production design builds, being quick, flexible, handheld and using a lot of the ambient light that was naturally present on the real locations Coogler pulled off the shoot with his tight knit crew on a budget of $900,000.

CREED - $35 Million

“I’m a big Rocky fan. You know, I kinda inherited my love for those movies through the love for my father. So I knew the movies really well. I knew the world really well. I kinda came up with this idea where a young guy interacts with basically my dad’s hero at a time in his life where he’s ageing and dealing with his own mortality in a way that we’ve never seen him deal with it before. It’s really about me and my dad. As much as I could bring of my own, you know, partial inexperience. Really, my dad, my relationship with him, as a heartbeat for the creative tensions there.” - Ryan Coogler

Contrary to what some may think, the idea for Creed was not one that was conceived by a studio. Instead, Coogler had been toying with the concept for a Rocky spin off with his USC friend Aaron Covington, just as a fun spec script while he was working on Fruitvale Station.

At the Sundance Screenwriting lab for his first film he was able to secure an agent who asked him whether he had any ideas for projects beyond Fruitvale. After explaining his concept for Creed his agent set up a meeting where Coogler pitched the idea to Stallone - the original writer, and of course, lead actor in the Rocky franchise.

After securing Stallone’s buy-in to get a script written, MGM paid for him and Convington to write the screenplay. Appreciating the fresh perspective on the story and his character, Stallone gradually agreed to come on board until MGM greenlit the project with a production budget of approximately $35 million.

In Stallone, Coogler found a new collaborator to work with.

“He’s also a producer on the film. He was comfortable taking a backseat here which is a big thing. He had written all the scripts, every single last one, for these types of films. What really made him excited was seeing this from the millennial perspective. You know, we’re talking about a 68 year old dude who is showing up in the cold everyday. And shows up for a day where we’re shooting four pages and he’s got 10 pages of character work that he did the night before. It was amazing and it was energising.” - Ryan Coogler

One example of Coogler’s openness to collaborations from his cast and crew happened when instead of Stallone throwing water in Michael B Jordan’s character’s face to wake him up as it was written in the screenplay, Stallone proposed that his character play old records instead, as it’s what he felt his character would do. They went with this suggestion and it made the cut.

To create a visual language for the film which was a little bit ‘slicker’ than Fruitvale Station, but which was still grounded by a similar photographic feeling of realism he turned to cinematographer Maryse Alberti - whose naturalistic work on The Wrestler he admired.

Rather than something more stylised like Raging Bull, they decided on a camera language which was more realistic and which at the same time paid subtle homage to the original Rocky film with its famous early use of the Steadicam - but didn’t copy the look.

“We looked back more at what not to do. Do you like this colour? Do you like this? No? Well, me neither. And taking the good things like the iconic thing of the steps and things like that. But, yeah, he was reinventing.” - Maryse Alberti, Cinematographer

One way that they reinvented the film visually was by making the final boxing match look more like it would be presented realistically on a modern TV broadcast by shooting at a deeper stop of T/5.6 and using a higher key lighting style.

They did this by building the ring on a soundstage and surrounding it with a 600 foot greenscreen wall which they could then replace with a composited crowd using visual effects. Her team lit the ring by rigging up square truss above the space from which they suspended 120 tungsten par can lights with different lights focused at different distances, to provide an even overhead lighting.

Because it’s tiring for actors to repeat these choreographed boxing scenes many times in a row and maintain the same level of energy, they shot with multiple cameras to get better coverage - in a slightly similar visual style to how big fights might be shot for TV.

This scene was covered with one camera on a technocrane, getting telescoping movement and wider shots, one camera on a steadicam which could roam around the ring, and two handheld cameras getting on the ground reactions.

They made the decision to shoot digitally on the Arri Alexa XT in 2.8K Arriraw with spherical Cooke S4 primes and some wide angle Angenieux Optimo zooms. She also used the Alexa Mini on a Movi for some scenes which need nimble camera moves through tight spaces such as when the camera tracked from outside the ring, through the ropes into the ring - which they did by passing the Movi off in the hand to a new operator.

Alberti chose the S4s as they flattered skin tones and rendered them nice and softly, which counteracted the digital grain they planned to add in post which roughened up skin a little bit.

Creed was therefore pulled off on a much larger production budget of around $35 million that leaned on established franchise characters, while also invigorating the series with a new perspective that used a larger crew to run more gear, involved building sets, shooting more time-consuming action sequences and incorporating more visual effects work in post.

BLACK PANTHER - $200 Million

“The biggest difference actually wasn’t in the restrictions. It was actually, like, in the lack of restrictions. When I was making my first film, dealing with not a lot of money you have a lot of limitations and it helps you actually move faster because you can’t do just anything. Maybe sometimes there’s only one place you can put the camera. You can only be in this location for two hours and then you have to go. It makes it easier. When you can do anything and that’s kinda what happens with a film like this. That’s what I found made it a lot harder.” - Ryan Coogler

A lack of limitations means that more preparation time can be put into the project during pre-production. As with all his movies, Coogler’s role as a director began with him being involved in writing the script.

An extensive period of prep time was necessary for this Marvel blockbuster undertaking which involved far more scope, intricate scenes and visual effects than any of his prior work had.

This required input from multiple heads of departments. For this he brought together many of his prior collaborators who’d worked with him since Fruitvale Station, and some even since his student short films days. This included editor Michael P. Shawver, production designer Hannah Beachler, composer Ludwig Göransson and cinematographer Rachel Morrison.

The director and cinematographer had many discussions with Marvel’s VP of physical production and with Geoffrey Baumann, who oversaw a team of 16 different visual effects vendors that were working on the film.

Practically, this prep work involved doing things like creating a previs - a rough animated version of the entire cut of the film - and mapping out how they would cover a scene using a 3D printed scale model of a set for a casino scene they would be constructing.

One of the moves that they came up with for this fight scene was a shot where the camera transitioned between different characters on the set’s two floors by flying through the air. They rigged a Movi gimbal onto a cable rig, which lifted the camera to the second floor. From there, another operator could grab the camera off the line and begin operating it.

While they were working on building this set, Morrison drew up a detailed lighting plan which involved rigging multiple overhead 8x8 and 4x4 blanket lights from SourceMaker, using higher output LRX Scorpion tungsten units to backlight and then using Varilite VL1000s which could be remotely swivelled to hit specific spots with targeted light. All of these fixtures were effectively ‘built into’ the set and rigged to a DMX board so that the levels could be adjusted quickly on the day of shooting.

Coogler turned his attention to detail for each character by focusing on things such as their costumes, which in the Casino scene were designed to take on the Pan African flag colours of green, red and black.

Since seeing all the costumes, even in the backgrounds of shots, was a priority to the director, Morrison needed to shoot at a deeper stop. This meant that rather than shooting on a large format Alexa 65 camera, Morrison chose to shoot open gate on a smaller sensor Alexa XT - which would yield a slightly deeper focus than a large format camera, with the Panavision Primo spherical lenses set to a stop between T/2.8 and T/4.

Coogler shot Black Panther with its larger scope story that involved more actors, preparation, visual effects, action sequences, stunts, bigger set builds, and even larger technical camera, lighting and grips setups.

However, he maintained his fingerprints on the project by co-writing the screenplay, using real world research to provide a level of depth to each character, working with his same close knit pool of collaborators, creating a deliberate visual style which was true to the tone he wanted and carefully telling the story through a lens which is empathetic and does justice to his characters.

What A VT Operator Does On Set: Crew Breakdown

In this Crew Breakdown video, let’s take a look at the VT Operator and go over what their role is, what their average day on set looks like, and a couple tips that they use to be the best in their field.

INTRODUCTION

The VT operator is one of the least talked about crew positions in film production, whether that’s on YouTube or the internet in general. They are responsible for orchestrating the live transmission and playback of video and sound via production monitors. It’s a role which is a necessity for any industry level commercial or feature film shoot and one that every technical film crew member should understand.

So I’ll use this video to try and fill in this information gap based on my observations from working as a crew member in the camera department by first unpacking the role of the VT operator, going over what an average day on set for them might look like and finally giving a couple tips which I picked up from watching experienced VT ops work.

ROLE

The process of shooting a movie involves capturing multiple takes of shots until the director is happy that they have a shot which will work in the edit. This means they need to be sure of both the technical aspects of the shot, such as the framing, camera movement and focus as well as the content of the shot such as the performances of the actors and the blocking.

Since getting the perfect shot can be a bit of an intricate dance, filmmakers need a tool which they can use to monitor these live takes and evaluate them. This is where VT comes in.

The video tape operator, also called video assist, playback operator, or VT, is responsible for setting up video monitors that have a live feed from the production camera or multiple cameras and then recording any takes that are done as a video file so that they can be played back after each take for the client, director or creative heads of departments to evaluate.

VT came about before digital cameras, when productions were shot on film. Since film needs to be developed at a laboratory before it can be viewed - which of course takes quite a while - film cameras couldn’t playback footage that had been shot on set.

Therefore, the solution was to record each take from a tiny, low res ‘video camera’ inside the film camera called a video tap. This signal from the video tap was recorded onto tape with a device such as a clamshell. This tape could then be fast forwarded or rewound and playback a low res video version of each take that the film camera recorded.

Since digital technology took over and footage is now recorded to cards rather than film, the role of the VT operator has evolved but is still based on the same principle of providing a live image on a monitor and being able to quickly playback video of takes.

There will usually be a few different monitors, reserved for different people on a film set.

This can be done by sending a video signal either through a wired connection to different monitors, or by using a wireless transmitter that can send a signal out to multiple receivers which are plugged into monitors.

The focus puller will usually get a feed directly from the camera with a sidekick receiver. The VT operator will then transmit or wire a feed to their station and run it through software on a computer such as QTake - which is the industry standard. They’ll then distribute this feed from the software to other monitors which may include what we call a video village - a tent with production monitors that display feeds from all the working cameras that are usually reserved for the creative agency, clients, the director and sometimes the producers.

Nowadays they’ll usually also be a wireless, portable director’s monitor on the set which is either put on a stand or can be handheld by the director as they move around and give direction to various departments and actors.

The cinematographer usually operates and exposes using a 5 or 7 inch monitor which is mounted directly onto the camera, but sometimes will request a feed to a specific colour calibrated monitor such as a Flanders Scientific screen that can be used to more accurately judge the exposure and colour of an image. Kind of like a modern light meter.

Although there’s a bit of an overlap between the 1st AC and the VT op when it comes to who is responsible for monitoring, usually the on camera monitor and the focus monitor feed is set up by the 1st AC, while the director’s feed and any other external monitoring lies with VT.

AVERAGE DAY ON SET

The kind of gear that VT needs to run will be determined beforehand depending on the kind of setups that are needed. For example, the gear for tracking vehicle scenes will be different to the kind of gear that is needed for a standard interior scene.

Therefore the first step is to plan for the kind of video transmission required, taking into account things like transmission range and how many monitors will be needed.

There are two, or actually now three, ways to send a video signal from a camera to an external monitor.

The first is what we call hardwiring. This is where a cable, usually an SDI cable, is plugged from a video out port on one side to a video in port on the monitor. The upside to this method is that the quality of the feed will usually be very solid. The only way to interrupt a hardwired feed is if the cable gets damaged.

The downside however is that if the camera needs to move then the cable will often get in the way and need to be wrangled by someone to avoid getting tangled up or becoming a tripping hazard.

The second method, wireless transmission, doesn’t require tethering the camera with the cable and is therefore the most popular. It involves attaching a transmitter, such as a Teradek, to the camera and plugging it into the camera’s SDI out port. This sends a live video signal of what the camera is recording through a wireless radio frequency to a receiver.

VT ops usually build their own custom mobile video trollies that they’ll mount the receiver to. This receiver will then get fed into some kind of a distribution converter or switcher that will get fed into a laptop or computer that runs macOS. This feed goes into the QTake software, where it can be controlled. This signal is then sent out of the video trolley through a hardwire, wifi or through transmission to a monitor.

The third, fairly new, way that video can now be transmitted is through a live stream using the internet. This was mainly done during Covid shoots and is now used for tracking vehicle work where the car will drive out of the range of the wireless transmitters.

With this technique, a video feed is sent to a modem with a SIM card and antennas which uploads the live video signal to the cloud and creates a streaming link. This live feed can then be viewed by anyone with access to the internet anywhere in the world - which is why it was used for remote shoots.

So, depending on the needs of the shoot the video assist will evaluate and provide a technical solution that aligns with the production’s budget.

Once they have a live video signal up and running to the required monitors they will wait until shooting begins. They will trigger video to record for both rehearsals and any takes that the camera rolls on. After the camera cuts, they will call out ‘playback’ and then loop the video footage of the last take that was shot on the monitors.

Using QTake software they will also label each take that is done. Giving it the same name as the scene, shot and take that is on the clapperboard. This is a way of archiving what has been shot and makes it easier to relocate previously shot takes - which is especially necessary when directors need to quickly track down a specific take from a scene that may have been shot weeks ago.

VT will also collaborate with the sound department to provide audio that is synced up with the video footage. If you’ve ever seen a photo of a director on set wearing headphones, they are for listening to a transmitted audio signal that is being captured by the sound recordist that is synced up to the video feed on the monitor.

TIPS

Earlier I mentioned that it’s commonplace for video assistants to label and archive each take. They may also take this one step further by marking specific takes. As they’ll usually sit near the director’s monitor if they hear the director make remarks about a take being good they’ll be sure to mark that specific take. The director may also directly ask VT to mark a take.

This often happens during the shooting of commercials, which involve a back and forth discussion between the director, the agency and the client - who need to approve each shot before the production moves on. So, if, say, the director thinks they got it on take four, they may ask VT to mark that take. If they have time they’ll then do a couple extra takes for safety. Then once they’ve got those extra takes in the bag the director will ask VT to loop the marked take on the client’s monitor and then go over to them to confirm that they are happy, approve that take and then the production can move on.

On some shoots, the video assist may be asked to perform a mix and overlay. This can be done using QTake software and involves overlaying video or images on top of a take. For example, some commercials may need to incorporate specific text or a company’s logo on a shot. VT can overlay and then position this logo so that the cinematographer and director can find a frame that compliments and accounts for this.

Or, there may be a series of planned match cuts that the director wants to do. VT can then find the shot that they want to match cut with, overlay it on top of the live feed and mix down the opacity of the other take. They can then position the frame for an optimal match cut.

Most software these days is able to auto trigger video to record. So when the cinema camera starts recording it will trigger the video device to record at the same moment and likewise it’ll cut when the cinema camera cuts. However, occasionally when working with some setups - such as some film cameras - the video may not auto trigger and it’ll be up to VT to manually start recording video once they hear the call of ‘roll camera’.

How Casey Neistat Changed Vlogging Forever

One reason that I, along with the rest of the online world, am drawn to Casey Neistat is because of the filmmaking in his videos. Although they may appear rough and handmade, if you look a bit closer you’ll quickly see that his films are backed up by an array of innovative filmmaking techniques that he uses to present stories as a creative, experienced documentary filmmaker.

INTRODUCTION

It may come as a bit of a surprise from a part time YouTuber, but I actually don’t watch many YouTube videos - well not now anyway. But there was a time when I was living in Japan around 2015 or 2016 where I’d watch every single release from one particular YouTuber every single day. Those videos were Casey Neistat’s daily vlogs.

There were a few reasons that I, along with the rest of the online world, were drawn to Casey Neistat. For one, he’s a super charismatic and entertaining person on camera with strong opinions. For another, the non-stop freneticism that is his life, and the amazing situations that he puts himself in, was incredible to see documented. This combined with an honest, pretty intimate view of his life and daily uploads created a super close ‘relationship’ with millions of online followers.

But there was something else that immediately drew me to his videos: the filmmaking. Although they may appear rough and handmade, if you look at his videos a bit closer you’ll quickly see that they are backed up by an array of innovative filmmaking techniques that he uses to present stories as a creative, experienced documentary filmmaker.

So let’s break down his approach, vlogging gear, some of the cinematic techniques that he uses and explain why they are the very backbone of what made Casey Neistat’s vlogs so groundbreaking.

STORY STORY STORY

You can have all the tricks in the book, but they mean nothing if they aren’t used to create some kind of narrative arc. So before we look at his specific filmmaking techniques let’s unpack how he constructs story in his films. Even his more freeform personal docs that document his day, still have a story arc to them.

He’ll sometimes start with a cold open, cut to a hint at what will happen, the setup, they’ll have him doing something, the content, and then he’ll wrap it up, the wrap up.

Within the broader story of a video they’ll also be these little mini arcs that follow the same formula.

This is the same introduction, body and conclusion structure that academic writers use, the same setup, action and climax formula that screenwriters use and the same way that oral storytellers present fables. It’s a formulae that for whatever reason resonates with humans.

Of course, as an experienced filmmaker he also mixes things up chronologically. But the way that he structures each day, video essay, or even long take interview using this kind of formula is foundational to creating structure out of the chaos that is life that acts as a hook that the audience can relate to.

He also uses titles, physical chapter markers, visual gimmicks (tape measure plane) and handmade stop motion animation to introduce locations, context or explain concepts that enforce the structure of the story - in the same way that documentary filmmakers do.

FILMMAKING TECHNIQUES

Although what Casey mainly does in his videos has been called vlogging, what his videos really are are personal documentaries. And, as with most personal documentaries, the content is prioritised over getting technically perfect shots. This means that some moments may be out of focus, over exposed, lit using the screen of a phone or include moments of him picking up a tripod.

Part of the appeal of his style is that he uses real filmmaking techniques but then deconstructs them a bit and leaves them rough around the edges, including moments of imperfection.

So, what are some of the practical cinematography and editing techniques that he uses to enhance his storytelling visually. One technique he uses a lot is the whip or swish pan.

For most of his techniques he shoots with the edit in mind. He quickly pans the camera off to the side to end a shot. Then in a later clip he’ll repeat this same movement as before and cut between these to get a seamless transition between locations.

If you break it down frame by frame you can see that he cuts the two shots so that the one ends and the next begins on a blurred movement. Because this happens so fast the eye isn’t quick enough to see exactly where the cut happens and two shots can be stitched together without it being noticeable.

This technique has been used quite often in cinema. Usually when filmmakers want a way to join two long shots together which need to be filmed in separate takes. For the smoothest transition possible it helps to make this cut during the most minimal frame possible such as a dark, blank wall - rather than a complex shot with actors.

Another editing technique he and a ton of other YouTubers use is the jump cut. This is where a cut is made that joins two shots which have the same, or similar, framing. Usually this means doing one take using a single clip and chopping out sections in the middle of it to exclude mistakes, fumbled lines of speech, or to just include the best bits of a take.

In more formal filmmaking this is usually avoided by shooting multiple angles and shot sizes of scenes and cutting between these different angles to smooth over any mistakes. However some movies, such as the French New Wave film Breathless, have also used this technique to deliberately break down the established forms of filmmaking. It renders a more ‘breaking the fourth wall’, ‘hand made’ feeling which fits the tone of Casey’s vlogs.

He also uses jump cuts to playfully push the story forward in time. By shooting a single take shot from a locked off, still perspective, he can move himself around into different parts of the frame and then in the edit, remove all of that excess footage and quickly cut between him in different positions. This makes him whimsically bounce around the frame and gives the feeling that time is passing.

Or he’ll sometimes combine this with a match cut where he uses an edit to transition between two frames that have similar compositional or subject traits - another technique found in cinema.

While he uses jump cuts to shorten and speed up his videos, he’s also done the exact opposite for certain videos to achieve a different effect. In some videos he has used long takes - where he lets an extended portion of a clip play without cutting. These tend to really suck the viewer into the moment and work well for heartfelt monologues - as long as those monologues don’t have any distractions or lapses in performance.

Like all of these techniques the long take has also been used in many films, often for moments where the filmmaker is trying to pull the audience into the world of the film and the performances on screen as much as possible without breaking the illusion with excessive cutting.

Another well worn technique he uses are timelapses. This is where footage is captured at a lower frame rate and then played back at a higher frame rate in editing software. This ramps up the motion of the footage, speeding it up.

This technique is often used by filmmakers as a visual mechanism to illustrate the passing of time. It’s particularly useful in vlogs because they often display a lot of action over a short period of time such as a day or even a few hours. Timelapses can be placed in between two shots to visually show the passing of time and that these two moments are not continuous.

Casey shoots his vlogs with a variety of different shots from a variety of perspectives. He shoots wide establishing shots, usually in the form of overhead aerial footage to establish the space that he is in. He shoots POV or point of view shots where he’ll point the camera in front of him to capture an image that mimics his perspective on what he is seeing.

Like in most documentaries he’ll grab observational footage of people, who sometimes engage with him behind the camera, or who sometimes appear natural and unaware of its presence.

He’ll also sometimes set up a frame on a tripod, record a bit of the environment and then enter the frame and start talking in an interview style. And of course he shoots the classic vlogging shot - a self portrait with a wide angle lens capturing himself as he talks directly to the audience through the camera - which he’ll handhold.

A large part of what photographically makes his vlogs so dynamic comes from the camera movement and framing. Casey is great at finding interesting angles and frames on the fly. He’ll mix the perspective between high and low angles or use framing devices such as this shot, where he places the camera inside a phone booth, to create a natural frame for himself while at the same time showcasing the dynamic environment of the background.

The camera moves largely come from him physically moving his body in different ways. Whether that be on his famous boosted board, a bicycle, surfboard, or just him walking.

Part of what makes the way in which he moves the camera so effective is because of the variety. Contrasting shots with fast motion, locked off shots, high angles, low angles, create a feeling that the story, through the cinematography and editing, is constantly getting propelled forward.

VLOGGING GEAR

So, how does he do this? Well, the answer is with quite a few different tools and cinematic toys. The cameras and gear that he’s used has changed quite a bit over the years but let’s go over the current setup he uses.

Most of his gear is, I guess, what you’d call consumer or prosumer because its relatively reasonable price points make it accessible to the general public. As I mentioned before, getting the shot is more important in his vlogs than ‘perfect cinematography’. Function rules.

He shoots aerials with a Mavic 2 Pro drone, that comes in a tiny form factor that fits in a backpack but which also resolves great images and puts it at the top of the consumer drone market.

He’s recently taken to shooting super fisheye POV and vlogging shots with the Insta360 X3 that he attaches to a pretty ridiculous selfie stick. And for most action or water sequences he uses a GoPro. At the moment the Hero 9.

So those are some of the more niche cameras that he uses. Now let’s take a look at his main vlogging camera setup.

For years he stayed in the Canon ecosystem, using the 6D as his main camera with either a 16-35mm or a 10-18mm wide angle zoom lens. However, he’s now moved to Sony and shoots his videos with a 4K workflow.

His main camera is the A7S III. It’s light, shoots in 4K, has slow mo capabilities, can shoot in super low light conditions, and importantly has a swivel screen so that he can see what he’s recording when he shoots in selfie mode. This is paired with his go to lens - the Sony 12-24mm f/2.8. A large part of his look comes from using super wide angle lenses up close, that distorts the edges of the frame a bit and maximises how much background we see in a shot.

Shooting at a wider focal length also minimises the amount of visible camera shake there will be when shooting handheld.

He attaches this setup to a GorillaPod, a lightweight, mold-able tripod which can act as a selfie stick and can also be quickly positioned in tight, small spaces as a tripod. He also carries a lightweight Manfrotto Element Traveller tripod, which is small, portable and can be used for higher elevation tripod shots.

Finally, he’ll mount a lightweight Rode VideoMic Pro+ shotgun mic on top of the camera to capture ambient sound or when he talks directly to-camera.

CONCLUSION

I guess the answer to the question ‘What makes Casey Neistat’s videos so groundbreaking?’ is that he effectively took a bunch of established filmmaking techniques and his own experience in documentary filmmaking and applied it to tell stories in a more deconstructed YouTube vlog format.

Although his videos appear super improvised, rough and chaotic - and to an extent they probably are - they are also carefully and thoughtfully shot, crafted and assembled with a high degree of filmmaking know-how - which wasn’t really the norm before Casey.

While a vlogger’s personality and the situations they put themselves in are of course a large part of the appeal, Casey’s vlogs changed the game by also applying a level of filmmaking that elevated the vlog genre as a whole.

Cinematography Style: Charlotte Bruus Christensen

Let’s look into Charlotte Bruus Christensen's philosophical approach to shooting movies and then take a look at some examples of the gear she uses to execute her cinematography.

INTRODUCTION

The visual language of cinema is to a large extent determined by the context of the story. Some moments need to be slow and creeping, some moments need to feel hot and pressured, while at other times it should feel organic and natural. Charlotte Bruus Christensen’s work can be characterised by an overall classically Hollywood, cinematic, filmic, widescreen look, mixed with naturalism, which then uses the context of the story as the basis for applying the correct psychological perspective.

In this video I’ll take a closer look at the Danish cinematographer’s work, by unpacking some of her philosophical thoughts on the medium and then go over some of the gear that she uses to physically bring stories to the big screen.

PHILOSOPHY

“It’s interesting how you hit those different genres. It adds to the way that you think about, you know, lighting a scene or moving the camera. I think it just gives you, a sort of, another way in technically and also style wise to how you approach a story. It gives you sort of a framework and then you think there are those rules but then you break them.”

From horror films like A Quiet Place to period dramas like The Banker and psychological mystery films like Girl On The Train, her photography has covered a range of different genres.When coming up with a look for a film she’ll use the visual associations with each genre as a kind of general jumping off point, but will then narrow down the look and sometimes go against expectations as things progress.

The process for preparing for each film shifts. For example when working on Fences, originally written as a play, with director Denzel Washington, a lot of the early focus went to working with the actors, and nailing down the feeling of how each scene would be performed using rehearsals. Whereas when working with a different director slash actor John Krasinski they would go over older films as references in the build up and then be much more flexible and reactive with how each scene was filmed once they arrived on set.

“For A Quiet Place, John Krasinski, the director and actor, both of us were like there’s something about Jaws. I know it’s not a sort of direct, like you may not spot that in there, but the ways they were sort of lining up a three shot and this while thing of in Jaws you don’t see the shark until very late. There’s things that inspired us. I think also it’s a very educational process that we all sort of constantly do. When you make a movie you educate yourself further and further and further.”

She uses these films and shots as references in a way that takes into account their tone, feeling and type of storytelling - rather than directly borrowing from their look. For example, using a classically slow, steady, reactive, quietly moving camera to build a feeling of tension in scenes. And then letting the horror come from how the performances are captured and how the actors react to the off screen threat.

This feeds into another cinematic technique that she uses, where a psychological approach to story is taken through the imagery. She tends to shoot scenes grounded in a similar widescreen, classical, filmic base look but then tweaks things like framing, camera movement and lighting depending on the idea or effect she’s after.

For example, the buildings and places in The Banker were almost as important to the story as the characters were. So to better present the spaces she shot many scenes from a lower angle with a steady frame that more fully displayed the height of the architecture in the background.

While a film like The Hunt, pulled more subtly from the Dogme 95 stylistic guidelines by shooting naturalistically on location and using a lot of handheld camera movement to present intimate, personal close ups of authentic performances.

So, although both these examples were bound by a similar warm, film-esque look with shallow depth, real locations and natural lighting - the subtle variations in her cinematic techniques differentiates how audiences may psychologically interpret these two films - while also maintaining her own perspective. She uses these little variations in different contexts to enhance the psychological feeling that she wants the audience to have.

“And then also a whole sort of psychological thing of how you make people nervous, you know. If they’re in court this thing of sort of shining light into their face and over expose them to make them feel so small and in the spotlight and sweaty and heat and all these sort of things you would do to make people break.”

These effects come from discussions with the director, combined with her own point of view on how they want the images to feel. To get the most out of collaborations with the director and to serve their vision, usually means helping get the best performances out of actors.

“The most important thing I think I really value and try very hard to create freedom for a director and the cast while also producing a cinematic image.”

This is a balance that most cinematographers have to tread between getting the best image that they can, while at the same time being flexible enough to compromise with the actors and people in front of the lens.

Sometimes this may mean changing a pre-planned lighting setup and adapting that on the fly when actors and directors come up with new ideas for blocking on the day. Or it may mean quickly having to re-frame to capture an actor that isn’t tied down to hitting a specific mark on the set.

More often than not this process takes the form of an organic back and forth discussion with the creative heads of departments. This is why it’s so important to be able to collaborate and compromise on a film set to best tie the ideas that are brought to the party into the best iteration of the story that’s possible.

GEAR

I mentioned earlier that most of Christensen’s cinematography has quite a consistent, warm, classical, filmic look to it. I’d pin this down to two gear selections which she regularly makes.

The first is her use of anamorphic lenses. Although she has shot in the Super 35 format with vintage spherical lenses like the Cooke Speed Panchros, the majority of her feature film work has used anamorphic lenses. Particularly the C-Series set of anamorphics from Panavision, which is sometimes supplemented by other more modern Panavision anamorphics like the T or G-Series.

These lenses create a native widescreen aspect ratio and render images with a natural smoothness and warmth to them that has long been seen as a trademark of traditional Hollywood cinematography.

The second fairly consistent gear selection she makes is to shoot on film. Of course this isn’t always possible from a production standpoint or necessarily the right creative choice for all films, but she has shot a large portion of her work photochemically on all the variations of Kodak Vision 3 colour negative film.

When she does shoot digitally she tends towards the more filmic sensor in Arri cameras, like the old Alexa Plus or the Mini. The choice to shoot photochemically is in part an aesthetic one, but it’s also one that is determined by the style of working that she’s after.

“The way you light the film, the way you work with film. You know, you’re on set. You look towards the scene. You don’t disappear into a video village and try things out. You look, you light, you use your light metre and you shoot. I think that for us there was a nice feel to that. And then, you know, obviously the very soft, cinematic look where we could really use the anamorphic lenses, you know, with the emulsion.”

Depending on the needs of each project or scene she’ll select different speed stocks. For the interior scenes on Fences she used the more sensitive 500T which allowed her to expose the darker skin tones of the actors at T/5.6 in the dim spaces while still having enough latitude to preserve the brighter information outside the windows without it blowing out. Whereas this interior scene from The Banker was shot on the less sensitive 50D stock. This finer grain film stock, along with her lighting, evoked the 1950s, Hitchcockian period look that she was after.

To enhance this look, she lit the actor with a hard light - an 18K HMI. The light beam was positioned and cut so that it hit the forehead and created a rim light highlight ping on the skin, which is reminiscent of older films from the period which used hard light sources in a similar way.

I think Chirstensen’s overall approach to lighting was influenced early on by her work on films by Dogme 95 directors like Thomas Vinterberg. This filmmaking movement came with various rules that included limiting the excessive use of artificial lighting.

Her lighting tends towards a naturalistic look, where the sources of the light, even when they are artificial, are motivated by real sources of ambient light. Therefore, coming back to those interior scenes from Fences, she spots the quality of the sunlight that is coming through the windows and supplements its direction and quality by using daylight balanced HMI units.

Then to balance out the look so that the actors do not appear too much in a shadowy silhouette she adds fill light using Arri Skypanels - which imitates and lifts the natural sunlight that comes from outside and bounces back, more softly, off the walls.

Most of her lighting uses this similar approach of supplementing the existing sources of light that are naturally present at the location, whether that’s in the form of sunlight, street lights at night, or artificial light from practical lamps inside a home. Just as she subtly tweaks her lighting in different ways that play to story, time period or some kind of motivated idea, the way in which she moves the camera is also an important feature of her work.

“If you’ve been busy with the camera, if it’s been handheld, or you’ve been running with the camera and you cut then to a still image then it’s like, ‘Oh my God. Something is going to happen.’ It was very minimalistic in a way. You move the camera a little bit or you cut from a running shot to still. These kind of very simple, minimalistic tools were very powerful.”

How the camera moves is often talked about, but what is discussed less often by cinematographers is the kind of movement that is present in two different shots which are cut next to each other. Something Christensen likes to think about is how to contrast two forms of camera movement - like a rapid dolly move to a slow creeping push on a dolly - for a more abrasive emotional effect. This contrast is especially effective when it’s set against the rest of the movie that is shot with subtle, slow, barely noticeable camera moves.

She uses a lot of these slow, steady, traditionally cinematic moves in her work which is done with a dolly and a track. Sometimes to get to lower angles she’ll ‘break the neck of the dolly’ and shoot from low mode.

Another consistent feature in her work is the use of a handheld camera. This is especially present in her early work with Dogme 95 directors, as shooting with a handheld camera was another of their aesthetic rules, but she’s also continued to use this technique, particularly for more intimate close ups, throughout various other movies shot in the US.

CONCLUSION

“I love going in and seeing the whole team and everything is going off. What you planned to do. And I come on set in the morning and go , ‘Really? Can I enter this and go in and say something?’ I always get excited about just the physics of the staff and the people and some mechanic that I love about this.”

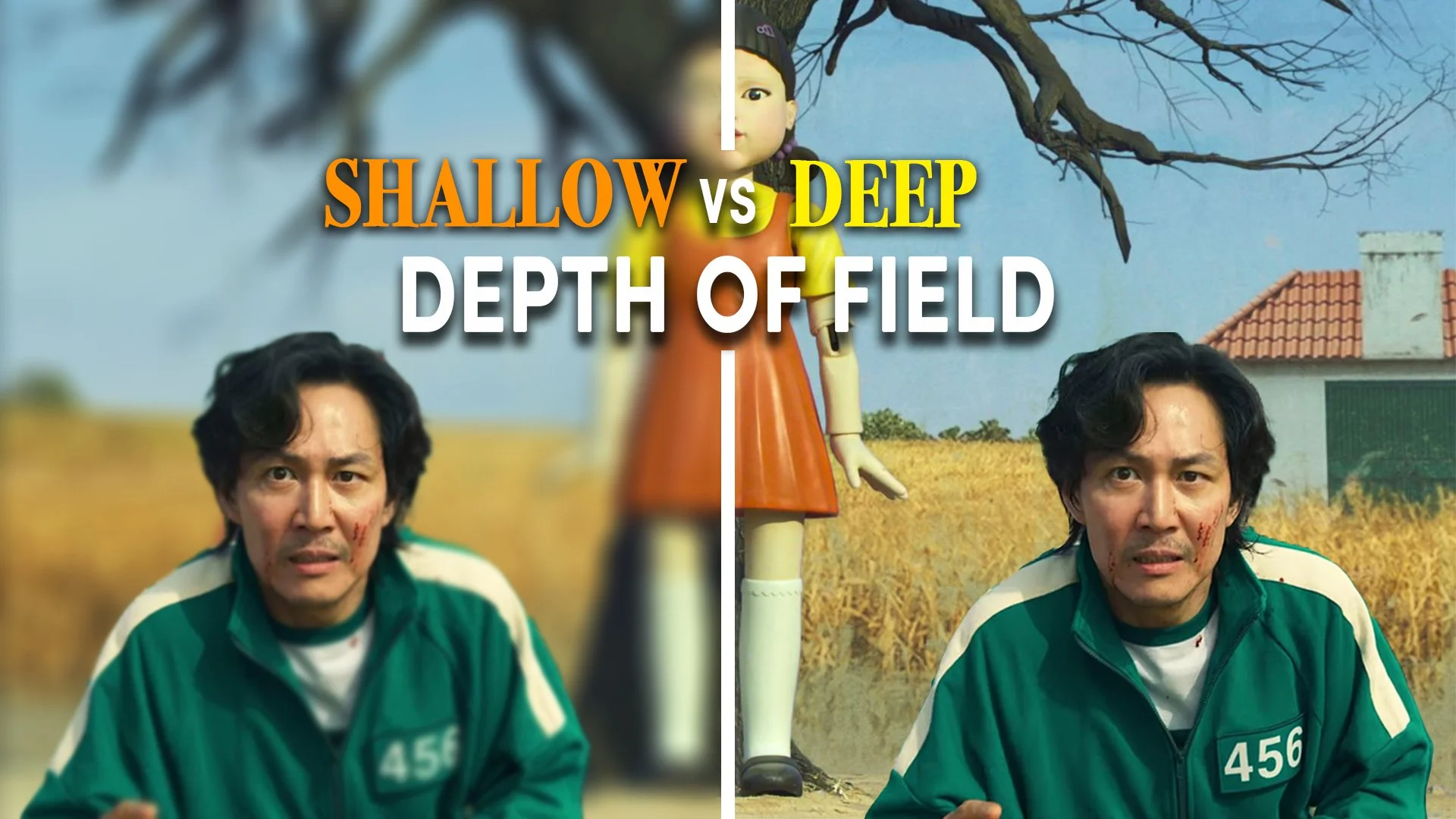

The Pros And Cons Of Shallow Depth Of Field

Let's dive into what depth of field is, the factors and settings that can change it and then go over some of the pros for shooting with a shallow depth of field, as well as go over some of the reasons why shallow focus may actually be undesirable.

INTRODUCTION

Ever noticed how some shots in movies have a blurry background, while in others everything is pin sharp across the entire frame? This is due to the depth of field of an image and is more often than not a conscious choice that is made by filmmakers.

Shots with a super soft, out of focus background have what we call a shallow depth of field. While those that have large areas of the image in focus have a deep depth of field.

Let’s break this down a bit more as we dive into what depth of field actually is, the factors and settings that can change it, and then go over some of the pros for shooting with a shallow depth of field, as well as go over some of the reasons why shallow focus may actually be undesirable.

WHAT IS DEPTH OF FIELD?

Depth of field is a measurement of the distance between the nearest point that a lens renders in sharp focus and the furthest object that is sharp.

For example, one could shoot a close up shot of a character on a telephoto lens where the nearest point of focus are their eyes and the furthest point of focus are their ears. In this example, the distance between these two points, the depth of field, is a measly 3 inches. This is what we’d call shallow focus.

In another example, a camera may shoot a long shot on a wide angle lens where everything from the foreground to the horizon is in sharp focus. In this example the distance between those points is so far that we just call it infinity. This is what we call deep focus.

Based on those examples, we can establish that there are a few different variables that change how much depth of field an image has. In fact there are three variables: the focal length, the distance to the in-focus subject and the aperture of the lens.

Shots captured with a telephoto lens that has a long focal length - such as a 290mm zoom have a much shallower depth of field than shots that use a wide angle lens - such as an 18mm lens - which will create a deeper depth of field. So one way to create a background with more blur is to choose a longer focal length.

The second variable for depth of field is determined by where the focus distance is set. The nearer to the camera that the subject is and the tighter the shot, the shallower the depth of field will become. This explains why when you shoot an extreme wide shot that focuses on the horizon most of the frame will be sharp.

Finally, the third variable that filmmakers can use to change the depth of field is the aperture or stop of the lens. The wider open the iris on the back of a lens is, the lower its T-stop will be and the shallower the depth of field it will produce.

One reason why fast lenses such as T/1.3 cinema lenses are desirable are because cinematographers can shoot them wide open to create a background full of soft bokeh.

When a long focal length lens, a subject close to the camera and a fast aperture are all combined - much to the horror and disgust of the focus puller - the depth of field that a camera captures will be very shallow.

Inversely a wide focal length lens, a subject far away and a closed down stop will mean that the depth of field will be very deep and the focus puller can relax.

There’s also a fourth variable, the sensor size, which doesn’t directly affect the image's depth of field but does affect it indirectly. Shooting on cameras with a larger sensor size produces images that have a wider field of view. To compensate for this extra width, cinematographers will either shoot on longer focal length lenses to produce a comparable field of view, or are forced to physically move the camera closer to maintain a similar frame.

As we now know, those two actions, using a longer focal length and focusing on a subject closer to the camera will both make the depth of field shallower.

PROS OF SHALLOW DEPTH OF FIELD

The biggest cliche about images with a blurry background is that they look ‘cinematic’. The idea of a ‘cinematic’ shot can’t only be tied down to a specific image characteristic. I mean, obviously there have been plenty of gorgeously shot pieces of cinema that don’t use a shallow depth of field.

However, sometimes cliches have an inkling of truth to them. To understand the link between images with a shallow depth of field and cinema, we need to go back to the days before digital cinema cameras.

In the early days of video, most cameras had little sensors, wider lenses and slower apertures. While movies captured on 35mm film used a larger film plane, longer, faster lenses.

So the ability to capture images using a shallow depth of field was technologically limited to filmmakers that shot for the big screen, while deeper focus had associations with the less highly regarded video format.

Although this has now changed, with advances in digital technology making it easy for even entry level cameras or smartphones to simulate a shallow depth of field, I’d argue that there’s still an unconscious mental association that persists between a shallow depth of field and ‘cinematic’ movies in the mind of the audience.

With that out of the way, I’d say that the single greatest practical use of shooting with a shallow depth of field is because it allows filmmakers to control what they want the audience to see and ‘focus’ their attention to.

The smaller the depth of field, the less information in a frame will be in focus and the more power the focus puller has to show where the audience should direct their gaze.

It makes it possible to more easily isolate a certain character or detail in a frame. The more you isolate a character from the background, the more they stand out and become the central point of the story. A shallow depth of field therefore empowers filmmakers to visually tell stories from a more subjective viewpoint.

Depending on the context, a shallow depth of field can also be used for other, more creative, applications. Because a super shallow, drifting focus makes images feel dreamy, it can be used as a tool to chronologically differentiate certain scenes from others - such as using it as part of a different visual language for flashback scenes.

Shots that drift in and out of focus may also be used as a deliberate technique to emulate a less controlled environment and make certain sequences like action feel faster, more panicked and more dynamic.

From a purely technical point of view, shooting a lens wide open also lets in more light and makes it easier to achieve exposure in darker shooting environments. This also means that smaller lighting setups will be needed for scenes in darker spaces, like night exteriors - where shooting at a deep stop is rarely practically possible.

Another technical point is that cinematographers choose certain lenses over others because of their visual characteristics and how they render an image. The wider the aperture and the shallower the focus, the more pronounced these characteristics, such as their bokeh and focus falloff, become.

It’s almost seen as a bit of a waste to shoot a beautiful, vintage set of lenses at a deep stop. As you close down to around T/8 or T/11 most lenses will become increasingly sharp across the frame and will be more difficult to differentiate from each other. So for those who want to create a level of soft texture to the images, shooting at a faster stop is prefered.

CONS OF SHALLOW DEPTH OF FIELD

While shooting with a shallow depth of field is wildly popular in the film industry, there are also some reasons and situations where it may not be desirable.

I mentioned before that shallow focus can be used to tell stories by guiding the audience’s gaze towards a specific part of the frame, but inversely a deeper focus can also be used to tell a story in a different way.

Shooting a film with a deep stop, where more of the frame is in sharp focus, allows the audience to peruse the environment and pick out information from it themselves - rather than having those details spoon fed to them with shallow focus by a filmmaker. In this way a deeper focus presents stories in a way that is subtly more objective.

Another persuasive case for a deeper depth of field is that it allows you to see more of the set and environment that the character is in. I remember a focus puller that I used to work with who would voice his surprise, especially at younger DPs, who would always shoot every shot with the aperture wide open and make the background as blurry as possible.

Why travel all the way to a beautiful location, or spend loads of money constructing an incredible set, only for the audience to not see any of it because the background is so out of focus?

Deeper focus shots that see the location are a useful tool for the audience to place where exactly the character is in their minds.

Moving on to the practical side, and being fully transparent, that focus puller may have advocated for a deeper depth of field because it makes their job of keeping the subject sharp much easier. The shallower the depth of field is, the less margin for error focus pullers have to accurately pull focus and maintain a higher ratio of shots that are usable.

This is why if there is a particularly challenging focus pull, the DP may chat to the 1st and stop down the lens a couple of stops to help achieve more accurate focus. If you’re short on shooting time, sometimes it’s better to sacrifice a smidge of buttery smooth bokeh in order to maximise the number of takes that will have usable focus. Rather have four usable takes for the director to work with in the edit than one take that is in focus that has a shallower depth of field.

Another case where a deeper depth of field may be preferred is when shooting a two shot. As the name suggests this is a single shot with two people in the frame. Sometimes these two characters may be placed at different distances apart from the camera. When shooting with a shallow depth of field, this may mean that only one of the people can be rendered in sharp focus, because the depth of field doesn’t extend far enough to the second character.

A solution to this is to shoot with a deeper depth of field and get the focus puller to do what is called splitting the focus. This is where the lens is stopped down and focused to a distance in between the two characters - so that the depth of field extends nearer to get the first person in focus, and further to get the back person in focus at the same time.

Before I mentioned that shooting wide open accentuates the interesting optical qualities of the lenses, however, for certain films the look may be more suited to shaper images. The more that a lens is stopped down, the deeper the depth of field becomes and the crisper and more accurately resolved the image will be.

This is particularly useful when shooting with certain old, wide angle anamorphic lenses such as the Cooke Xtal Express set. The wide focal lengths in this set have a huge amount of focus falloff when shot wide open with the ‘sweet spot’ of the lens only rendering sharp focus in the very centre of the frame.

So to minimise actors looking soft on the edges of a shot and to sharpen up the lens to an acceptable level, some DPs prefer to shoot these lenses with a deeper focus at a stop such as T/5.6 or T/8.

How Virtual Studio Sets Are Changing The Way Movies Are Made

A recent advance in filmmaking technology is taking place in the field of film sets. This is being altered by improvements in LED wall technology combined with gaming engines. Let's take a look at how we’re quickly heading towards a point where the idea of shooting big budget shows and movies in real world locations is becoming less and less popular.

INTRODUCTION

Filmmaking is a creative discipline which is constantly changing and being driven forward by changes in technology.

Whether that’s the change from black and white film to colour, the introduction of anamorphic lenses that led to a widescreen aspect ratio, or the creation of digital cinema cameras and the advances in CGI and post production software which allowed filmmakers to artificially create shots that wouldn’t have been possible before.

Advances in technology have an undeniable influence on filmmaking.

One of those recent advances which I’ll look at in this video is the way in which the film set, the space in which a movie is physically shot, is being altered by improvements in LED wall technology combined with gaming engines. And how we’re quickly heading towards a point where the idea of shooting big budget shows and movies in real world locations is becoming less and less popular.

WHY NOT SHOOT IN REAL LOCATIONS?

If you’ve never been on a film set and don’t know much about how movies are made it may surprise you to find out that on many productions the environments that the characters are filmed in are not actually locations in the real world.

There are two types of filming environments that can be set up, real world places - which is called shooting on location - and fake environments that are artificially created to mimic a space - which is called shooting in a studio.

You may wonder what the point of shooting in a studio is when the real world has no end of beautiful, easily accessible locations. It boils down to a few reasons.

The first considerations are time and money. Even though it’s costly to rent studio space and build a set from scratch, sometimes this is still a cheaper option than shooting on a real location.

For example, some scripts may require multiple scenes shot in a diverse range of interiors. It may be cheaper and easier to build one tent set, one interrogation room set, one office set and one prison cell set next to each other in a studio which the crew can quickly bounce around between, rather than doing multiple hour location moves, or even inter-country moves, between each real world location.

Another more obvious reason to shoot on artificial sets is because it may be impossible, or at least very difficult, to access certain locations in real life. Trying to gain access to shoot in the Oval Office probably isn’t going to go very well.

Thirdly, shooting in a studio gives filmmakers a far higher degree of creative and practical control. When you set lights in a studio they will provide a consistent level of illumination for as long as necessary. When you’re in a real world location the sun will move throughout the day and the quality of the ambient light will constantly change.

When shooting outside in real locations it might rain, there may be clouds or there may be full sun. You’ll constantly have to adapt your plans and scheduling depending on weather forecasts and what kind of look you’re after. This isn’t isn’t an issue when shooting inside a soundstage where you can create your own permanent artificial sun.

Finally, shooting in a studio is sometimes necessary to achieve certain shots with specific gear. For example, doing a telescoping movement through an interior on a Technocrane, or getting a high bird’s eye view perspective, may only be possible in a studio where that gear can practically be brought into the space and where set walls can be moved around, or the set ceiling removed, to accommodate the gigantic rig.

HISTORY OF ‘VIRTUAL’ SET TECHNOLOGY

“Every step that we take in the film business is incremental. Digital didn’t just appear on the scene. It had been precursured with Genesis’ and DVs. It didn’t appear all of a sudden. It feels like it sometimes that the adoption of digital happened overnight. But it actually didn’t.” - Greig Fraser ACS, ASC, Cinematographer

When you compare movies from the 30s and 40s with contemporary films it’s much easier to see which sets are not real in the older films. This background is clearly not real, but what about this one? It may look like a real interior location but this background is actually created by a giant LED screen.

To better understand this cutting edge soundstage of the future it’s best to start at the beginning and go through a brief historical overview of quote unquote ‘virtual set backgrounds’.

One of the earliest ways of creating fake backgrounds in movies was with matte paintings or painted backdrops. This is where an artist was employed to physically paint a landscape or set background onto a sheet of glass. The painting would try to incorporate as much of an illusion of depth as they could using a 2-D surface.

Actors, foreground set design and props were then filmed and placed in front of these painted backdrops to trick the audience into thinking they were at a real location.

To save on the inflexibility, lack of photorealism and lack of camera movement, the next technological step forward used the same idea but replaced it with film projection.

Rear projection, as it was called, used a large screen surface with a film projector mounted behind it that could project photorealistic backgrounds that had been pre-filmed at a real location. This also meant that moving backgrounds could now be projected to give the illusion of motion.

Although this was later improved upon with front projection, it still didn’t always sell these backgrounds as 100% reality.

Moving forward in time to digital effects, the next technological breakthrough came from chroma key compositing. Again, this used a similar principle as before, but instead of painting or projecting a background image that could be captured in camera, this time a consistently coloured blue, or green screen backdrop was used.

Green and blue are the most commonly used background colours for chroma keying as they are uniform, distinct and differ significantly from the hues that are present in human skin and most other human environments.

Using software, this specific green or blue channel of colour can be keyed out and removed from the shot. A secondary shot can then be layered behind this foreground layer in post production, replacing the background with whatever footage they’d like and creating the illusion of depth.

Although this technique has been widely used to create artificial set backgrounds for years, it’s still not perfect. One of the main challenges of shooting with a chroma key is that it does not provide realistic lighting, like a real life ‘background’ in a shot would.

“Cause there’s always the problem.You know, you’re flying above a planet like Earth. If you do a barrel roll how do you suitably light that all around? You’re not going to do a real barrel roll. So trying to solve that problem led us to creative volume.” - Greig Fraser ACS, ASC, Cinematographer

LED VOLUME WALL

Creative volume, or volume lighting, is a way of describing the latest innovation in virtual background technology.

“The stage of the future is a series of lights on the walls. It’s walls that are made of light emitting devices.” - Greig Fraser ACS, ASC, Cinematographer

This is a gigantic LED wall, and sometimes also a ceiling, which can display and playback photo-realistic video or stills using Epic Games’ Unreal gaming engine - kind of like a massive TV. This system can also use camera positional data to change how the background moves. So when the camera moves, the background can move accordingly, creating parallax and an almost perfect visual illusion.

“There’s another shot on that same ice pathway on the ice planet where the camera was booming up. And in camera it’s perfect. There’s one long walkway disappearing. Obviously there was a practical walkway and then the digital wall. And so the digital walkway, as the camera’s booming up, had to change its relationship so that the perspective from the camera was the same.” - Barry Idoine, Cinematographer

This enables most shots to be done completely in camera without much post production tweaking necessary. This wall also solves the lack of interactive lighting problem that’s encountered when using a green or blue screen.

Greig Fraser used this system, which they called The Volume, to shoot large portions of The Mandalorian in studio. Having no green screen meant that there were no green light tinges to the set, or green reflections on the actors metallic suit.

The Volume is a 20 foot high, 270 degree wall with a circumference of 180 feet, complete with a ceiling. This newest iteration of the technology featured LED pixels which were only 2.84mm apart from each other - close enough for it to produce photorealistic backgrounds.

This allows crews to use the gaming engine to map 3D virtual sets as a background using the same technique as early matte paintings or rear projection but with the added bonus of creating realistic parallax movement that mimicked that of the camera movement, and interactive lighting that provided naturalistic shadows, illumination and reflections.

These backgrounds are created by using a series of digital photographs taken on a camera like a Canon 5D which can then be stitched together to create one stretched out background that covers the 270 degree wall.

To change between locations in different cities, or even different planets, the production design crew just needs to swap out the foreground art elements, like the floor and any props near the characters.

The correct background will then be set on the LED wall, any lighting tweaks will be adjusted, the actors called in, and then they’re good to go. This allowed them to be able to change between an average of two different locations in a shooting day.

“Instead of blue, green screen, we can now see the environments and actually see them as live comps. For all intensive purposes. We’ll actually be able to go inside a car on stage and for the actors and the photography to look like you’re actually driving.” - Lawrence Sher, ASC, Cinematographer

One of the big advantages of working like this is that cinematographers can use this LED screen to control the ‘weather’ however they want. If they want to shoot the same sunset for 12 hours at a time they can do so. If it needs to be cloudy, or sunny that can be accomplished by switching out the background and adjusting the light.

One limitation that shooting in this way still has is that the actors need to be about 15 to 20 feet away from the LED wall in order to create enough separation between the actors and background for the image to look realistic.

Apart from this one downside, this new technology of creative volume is a massive step forward in virtual set technology, which allows filmmakers a new degree of studio control and an ability for cinematographers to capture the images that they want in camera without leaving it up to post production.

Also remember this technology is still in its infancy. As it continues to get used on more shows in the future, such as the upcoming Netflix period production 1899, it will continue to improve, costs will slowly reduce and it will become more user friendly and faster for crews to work with.

We’re rapidly approaching the stage where filmmakers will be able to shoot scenes relatively easily in whatever photorealistic environments they imagine - without even needing a ton of post production manipulation.

As always technology pushes filmmaking forward, and will hopefully bring the industry back to the sweet spot of capturing films as much in camera as is possible.

Getting Kodak To Bring A Film Back From The Dead: Kodak Ektachrome

Now that the much beloved Kodak Ektachrome is back on the market after bring discontinued, let’s take a closer look at how exactly the film was resurrected, break down what makes Ektachrome different to other existing Kodak films, and look at how 35mm motion picture Ektachrome was brought back by special request to shoot the second season of Euphoria.

INTRODUCTION

It’s 2013. The digital camera has been introduced and you can now capture images with the click of a button. It soars in popularity while film sales plummet.

In a move to cut costs Kodak begins discontinuing its more niche films. Finally, all the variants of the legendary Kodak Ektachrome for both stills and motion picture got the chop. Cut to 2017.

“Kodak is proud to announce the return of announce the return of one of the most iconic film stocks of all time: Kodak Ektachrome.”

Now that the much beloved Kodak Ektachrome is back on the market, let’s take a closer look at how exactly the film was resurrected, break down what makes Ektachrome different to other existing Kodak films, and look at a film industry use case by going over why Ektachrome was used to shoot the second season of one of the most popular contemporary TV shows.

HOW EKTACHROME WAS RESURRECTED

Kodak started ceasing manufacturing Ektachrome 64T and Ektachrome 100 Plus in 2009. This was quickly followed by the rest of the line up until 2013 when all Ektachrome products were scrapped.

After seeing a bit of an uptick in the sales of film - especially in photography - Kodak made the move to bring the emulsion back. However it was no easy task. Manufacturing film on an industrial scale requires significant investment.

You can think of making a filmstock as being kind of like baking a cake. First you need to assemble all of the ingredients.

This is where Kodak hit the first snag. Because it had been discontinued from the market, it was difficult to find suppliers that would supply them with the necessary ingredients - or chemicals - to make it.

Ektachrome is a complex film that requires about 80 different chemical components. Eventually they managed to source or manufacture all the necessary ingredients and could begin producing and testing the new film.

This starts with using a cellulose triacetate base - a plasticy substance - which is then coated with multiple different layers of chemicals. These chemicals are mixed in different containers in the dark and applied to the support roll until it is coated. It is then cooled, dried and is ready for shooting where it will be exposed to light for the first time.

Initially Kodak rolled out the film so that it could be shot in 35mm by still photographers, in Super 8mm cartridges and in 16mm. However, 35mm motion picture Ektachrome wasn’t made available. Well, not yet anyway. But we’ll come to that later.

Once the Ektachrome film has been shot it can then be developed in an E-6 chemical process where the image emerges and is set so that it can be viewed and worked with under light.

This development process starts by passing the film through a chemical bath in the same way as colour negative film is in C-41 processing. But, because it is a reversal or slide film, it also has an extra step with a reversal developer that turns it into a positive.

But, you may wonder, what exactly is reversal film?

WHAT IS EKTACHROME

In a previous video I went over Kodak’s Vision 3 colour negative film, the most popular stock for motion pictures. When this film is shot and then developed it produces a negative where the colours and areas of highlights and shadows are inverted. This negative is scanned and then digitally converted to a positive image so that the image is flipped back to normal.

Kodak Ektachrome works differently. It’s a reversal film which is different to a negative film.

This means that when it is shot and developed in the E-6 process that I mentioned before it produces a positive image on the film. So the image can immediately be viewed by just projecting light through it and when it is scanned you get a positive image without needing to do any conversions.

If this is the case then why is negative film more commonly used than reversal film?

One reason is because reversal films have a much tinier dynamic range than negative stocks do. A modern colour negative stock like Kodak’s Vision 3 range is capable of capturing detail in an image with up to around 14 stops of dynamic range between the deepest shadow and the brightest highlight.

So it can see details in extremely dark shadowy areas metered at f/ 1.4 without going to pure black, while also maintaining details in super bright areas of the image up to f/ 180 without blowing out to pure white.

Ektachrome on the other hand has a far smaller dynamic range of about 4 or 5 stops. So if it is set to capture details in shadows at f/1.4, the highlights will start to blow out at only f/ 5.6.