Why Most Movies Are Shot On Arri Cameras

There is one particular brand of digital cinema camera that far and above is the most selected when it comes to high end productions. Let's take a look at why cinematographers choose to shoot on the Arri Alexa.

INTRODUCTION

“I think digital cameras…they’re all tools. It depends on the project. You choose a different camera like you used to choose a different film stock.” - Roger Deakins, Cinematographer

You hear cinematographers claim all the time that a camera is just a tool. One of many tools that can be selected from their cinematic toolbox. However if we look at the statistics, there is one particular brand of digital cinema camera that far and above is the most selected.

From the 2022 Best Cinematography Oscar nominees, four out of five productions used Arri digital cameras. Out of the Best Picture nominees that number was six out of ten.

You may think that this is just coincidence and we need a larger data sample size. Well then, from the 2021 Best Cinematography nominations four out of five used Arri. And the 2021 Best Picture nominees? Five out of eight.

If you keep going back it’s easy to see a clear pattern emerge. Most films these days are shot on Arri digital cameras. So, based on my own experience of working in the industry with these cinema cameras, I’ll explain the four main reasons that I see as being responsible for why most cinematographers on high-end productions select to shoot on the Arri Alexa.

HISTORY

“The Alexa is my digital camera of choice. It has been since it came out.” - Ben Davis, Cinematographer

Someone might say it’s as simple as Arri cameras produce the best looking image. But there’s more to it than that.

To understand why Arri’s digital cameras are so popular we need to understand how the movie industry operated before digital when all productions were shot on film.

Due to the prohibitively high cost of film gear and cameras, they need to be rented out for films by production companies on a daily or weekly basis. There were two dominant gear manufacturers that emerged to produce this niche rental equipment: Panavision and Arri. A key difference between them is that Arri sells their equipment to third party rental houses or individuals, while Panavision exclusively rents the gear they produce.

Each constructed their own camera system that had some differences, such as Panavision cameras using a PV lens mount and Arri cameras using a PL mount. However these cameras were all built around a standardised way of working that accepted most third party gear accessories, such as using 19mm rods to mount a mattebox. This meant that crew with different gear accessories could jump from a Panavision to an Arri system on different jobs without needing separate kits.

When digital began taking over from film, Panavision and Arri needed to come up with a digital alternative to their film cameras that could be interchangeable with existing lenses and gear accessories.

Over the years, many working cinematographers had built relationships with these companies and had a track record of exclusively using their gear. So when film changed over to digital they naturally were drawn to what these two companies had to offer.

Panavision produced the Genesis using some of Sony’s digital imaging technology which had a 35mm sized sensor. After early operational issues were fixed and the Genesis began seeing some initial use, it was quickly overshadowed upon the release of Arri’s competing camera the Alexa.

The quality of the Alexa’s image, its usability and basic ProRes direct-to-edit workflow and being able to be privately bought up by a range of individuals and companies around the world meant that the Alexa took off, leaving the Genesis in the dust.

COMPATIBILITY

“It was kind of scary for me because…until then all my movies had been on film…Of course for me it was no doubt that if I was going digital it was going to be Alexa…I knew the Alexa would be the camera…that looked more the way I used to work with film.” - Natasha Braier, Cinematographer

When it came to this transition from film to digital cameras, Arri tried to make this leap as smooth as possible.

The Alexa was designed to be compatible with existing lenses and film equipment. Importantly, the user experience was also designed around the way that film was shot. Their camera had a recommended native EI, like a film stock, and had a menu screen on the camera which was simple to operate, which was based on the same few settings available on film cameras, like shutter angle.

Other menu systems of competitors like the Red One were a bit more convoluted and had more requirements such as needing to do ‘black shading’ to recalibrate the black balance of the camera.

This meant the Red’s menu was more technical, like a computer, which I think appealed less to many experienced cinematographers who were used to working on film cameras that had limited settings. The Arri menu was a far easier transition.

Initially the Red also had a more complicated RAW workflow than the Arri’s ProRes one.

Over time, Arri added more Alexa cameras to their line up featuring different body sizes and formats all based on the Alev sensor. This meant that cinematographers could choose between mini cameras, large format cameras, studio cameras, or even 65mm cameras and maintain the same Alexa look and compatibility in whatever format they needed.

Arri accessories, such as their wireless follow focus, are also compatible with their cameras. It’s easier for camera assistants to work with both an Arri camera and Arri accessories. Kind of like having a Macbook and iPhone from Apple, rather than a MacBook and an Android phone.

Using Arri accessories on a Red is of course possible, but it limits some features such as changing settings or playing back takes remotely from the focus handset, and requires additional elements such as an R/S cable to run the camera.

Overall Arri’s simplicity and compatibility won out amongst cinematographers making the jump from shooting on film to shooting digitally.

LOOK

“I think the Alexa at the moments is the best camera out there…I thought that the image quality just in terms of its resolution and just that tiny little bit of movement from the pixels moving or whatever. The Alexa just has a little bit of life to it and I think if you go too far the image becomes lifeless. So I like that bit of texture it has.” - Roger Deakins, Cinematographer

We now get into probably the biggest reason most cinematographers love the Alexa: its look.

The Alexa is favoured for producing excellent, flattering skin tones, colour that feels filmic and resolving detail in a way that balances a high resolution with an organic texture.

This is due to two factors: the camera’s sensor and its image processing ability.

The Alev CMOS Bayer sensor that is found in the Alexa has a high number of photosites that balances image sharpness with a high dynamic range and low noise. It has a low pass filter that blocks artefacts and an IR and UV filter which avoids strange colour effects but leaves enough of the red spectrum intact to deliver pleasing skin tones.

The image processing of the Alexa was designed by Arri colour scientists who had developed their ARRISCAN and ARRILASER film scanning technology and were able to render colour in a very natural way.

While companies like Red pursued high resolutions, Arri took their time and focused largely on colour science - which to many cinematographers was, and still is, more important since most projects still get finished at a 2K resolution.

RELIABILITY

“I also bought the very first Alexa Classic you know when it came out and I go you know I’ll be fine if it’s useable for three years and it ended up being a functioning tool and I still use it…the longevity of these products has been amazing.” - Phedon Papamichael, Cinematographer

Finally, the durability and reliability of the Alexa is incredibly renowned across the industry.

As cinema cameras are designed to be rented out and used regularly and over many years in the extreme outdoor conditions that movies are shot in this is an important factor.

While most high end cinema cameras now have a high degree of reliability, during the early development of digital cinema cameras there were many horror stories of cameras breaking down. The Red One had a reputation for being temperamental and overheating, while the Alexa was a solid workhorse with incredible reliability.

As I say, although these reliability issues from competing cameras have been smoothed over, in the early days I think this made some people nervous to shoot on a Red and gave their cameras a bit of a stigma, as time on a film set is extremely valuable and waiting for a camera to cool down before you can reboot it wasn’t very appealing.

I’ve worked with Alexas that are many years old on beaches, in deserts, in extreme temperatures and never encountered any issues. Arri’s track record of robustness, reliability and the longevity of their cameras remains to this day.

CONCLUSION

Overall I’d say these four factors: Arri’s historical legacy in the film industry, the compatibility and ease of use of their products, the all important look, and their reputation for reliability, are what has made them the default choice for most cinematographers working today.

So much so that, as a camera assistant, when you work on any camera other than an Alexa it’s seen as an exception to the norm. I don’t see this trend changing any time soon, especially once they release their much anticipated Super 35 4K camera.

Why Some Shots In Movies Feel Different

Ever notice how some movies totally wrap you up in the world of a character to the point of it being claustrophobic and uncomfortable, while other movies make you feel more like you’re just observing events in their lives unfold in a more detached way? Much of this tone and feeling is a result of the filmmaker’s choice of shot sizes.

INTRODUCTION

Ever notice how some movies totally wrap you up in the world of a character to the point of it being claustrophobic and uncomfortable, while other movies make you feel more like you’re just observing events in their lives unfold in a more detached way?

Much of this tone and feeling is a result of the filmmaker’s choice of shot sizes.

To better understand the impact that different shots have on an audience I’ll first go over the basic shot sizes that are used by filmmakers and then dive into the effect that different types of shots, and how they are edited together, have on an audience.

SHOT SIZES

Before we get into their psychology we need to understand the basics. Shot size refers to the camera’s field of view and the width of the frame relative to how a character is placed in it and how much space they occupy.

Different shot sizes can be achieved by physically moving the camera closer or further away from the subject, or by using different focal lengths. The lower the focal length number the wider the field of view is.

So, let’s familiarise ourselves with the vocabulary that filmmakers use to refer to the width of a frame. This vocabulary helps crew members to quickly communicate their vision and is based on conventions which have been established over many years.

Starting on the widest end of the spectrum we have an extreme long shot or extreme wide shot. This is where the subject or character is totally visible and only takes up a tiny fraction of the total frame. They are used to provide a vastness and scope to the location or landscape of the story.

Due to this they are often used as establishing shots - the first shot that begins a scene and sets the context and broader space that the scene takes place in.

Moving in a bit we come to the long shot or wide shot. Like in an extreme wide the subject is shown from head to toe, however unlike an extreme wide the character now occupies more space in the frame. They are the main focus of the shot now rather than the landscape.

Wides are also commonly used as establishing shots and to show the full body actions of a character.

Next up, we push in further on the character into what is called a medium shot. This is where the bottom of the frame starts from above the waist and the top of the frame includes their head. Because we are closer to the subject we can now read their facial expression and performance more clearly, yet we are also wide enough to capture some of their upper body language and actions.

There are also a few variations of this shot that have some different names. A medium long, three quarter or cowboy shot is slightly wider than a medium shot, usually starting from the knee or thigh region. The cowboy derived its name from its regular use in western films. The slightly wider frame allowed the audience to see both the actors face and their guns that were slung around their waist.

The close up tightly frames the face of the character so that they take up almost all the space in the shot.

The bottom of the frame usually sits just below the chin at around the shoulder level and the top of the head is either included, or framed out - which is sometimes called giving the actor a haircut. There are many different degrees of width that a close up can be shot in, depending on how intimate the filmmaker needs the shot to feel.

Finally we can push in even closer to an extreme close up. This is a shot that is so tight that all we see is a detail or single feature of the face, such as the eyes. Extreme close ups can also be used to photograph objects that hold value to the story, such as text.

An extreme close up also goes by the name an Italian shot, due to its regular use by Sergio Leone in many of his Italian Western films.

THE EFFECTS OF DIFFERENT SHOTS

When you pick up a camera and decide to shoot something, the shot size that you choose will first and foremost be determined by what you choose to include in the frame and what you choose to leave out.

When someone asks you to take a photo of them on a phone, do you get right up in their face and take a close up, or back far away to an extreme wide shot? You probably wouldn’t do either. Because the information that you need to include is them and perhaps some of the background. Most people would take a photo with a frame somewhere in between those two extremes.

Whereas for action scenes, we tend to stick to wider shot sizes for the simple reason that we need to be able to see the overall action in order to know what is going on. And if we cut to a close up of a specific detail, chances are the filmmaker wants you to notice that piece of information.

So, information is the one key effect that choosing a shot has. The other important consideration is the emotion or feeling that comes from framing a shot in a different way.

While there aren’t any definitive rules set in stone that apply to every single film ever made when it comes to interpreting emotion from a shot size, I think a broad rule can be generally applied.

In life, our proximity to a person defines our emotional relationship to them. The closer we are to someone the more intimate our connection to them is, and the further apart we are the more observational and emotionally distant we are to them.

Being face to face with a partner has a different emotional feeling than watching the actions of someone you don’t know from across the room. The same principle can be applied to shot sizes.

The more of the frame a character takes up, the more intimate and personal our connection to them feels. So having a close up of a character means the audience will unconsciously feel a greater sense of connection towards the character in that moment. It’s as if the filmmaker is saying, ‘Make sure you notice this detail or emotion. It’s very important.’

While viewing an entire movie shot in wide shots will distance the audience emotionally from the character and their actions, making it feel like we are passively watching them, rather than being transported directly into their head and thoughts.

Now the reality is that most films are shot with, and include, a variety of shot sizes. This is so that different pieces of performances can be chopped together continuously and without jump cuts. Having different shot sizes to work with also allows the editor to control the pacing and emotional arc of the cut by cutting to different shot sizes that come with different emotional connotations.

For example, a textbook scene will start with a wide establishing shot of the location. then cut to a wide of the characters in a scene. As we get to know those characters we’ll cut in closer to a medium and go back and forth on mediums as the characters exchange general dialogue. Then as what the characters are saying, and how they are saying it becomes more important and intimate the editor will start to cut to close ups.

By cutting from wider shots to progressively tighter shots, the scene is able to begin by establishing the information and space of the location, and then slowly shift the audience’s perception from a more general observation of characters to building up a more personal connection with them as we get to know them.

While this is the general rule, shot sizes can be manipulated in other ways for effect. For example, Son of Saul uses close ups of the lead character for almost the entire film. This emotionally puts you in the shoes of that character and makes the space of the film more claustrophobic and confusing as we never cut wide enough to establish the space.

An opposite approach can be found in a film like Memoria, where we stay wide for most of the film. This presents the actions to us as something to be observed from afar in a more objective way.

Editors can also play against convention by flipping the idea of starting wide and cutting in closer.

The opening to The Deathly Hallows does this by starting on a bold opening statement. We cut from an extreme close up, to a close up, to a medium shot to an extreme wide. This creates an emotional arc that moves from extremely intimate to more detached, and controls the flow of information, providing context and establishing more of the world each time we cut wider.

CONCLUSION

In shot sizes, filmmakers hold a very valuable tool in their hands.

Like a puppet master they can use the size of a shot to manipulate what the audience does or doesn’t know and, perhaps more importantly, to manipulate the very emotions of the audience and the relationship they have with the characters on screen.

6 Basic Camera Settings You Need To Know

Let’s examine 6 of the most important camera variables or settings that can be changed: EI, shutter angle, aperture, ND filters, white balance and frame rate.

INTRODUCTION

For anyone who wants to take photography or cinematography more seriously, the first step is to distance yourself from the dreaded ‘auto’ setting on a camera, move the knob over to ‘manual’ and start to understand the basic camera variables or settings that change the way that an image is captured.

Professional image makers choose to manually manipulate these settings to maintain complete control over how an image looks and not leave those creative decisions down to the whims of automatic camera software.

In this video I’ll examine 6 of the most important camera variables that can be changed. These settings affect the image in different ways and can be placed into three separate categories: exposure settings, colour settings and motion settings. These 6 variables have both technical value that can be used to control how an image looks, and also have creative value that changes the effect, mood or feeling of an image.

EXPOSURE SETTINGS

Exposure refers to how dark or light an image is. This is determined by the amount of light that goes through a camera's lens and hits the sensor of the camera - where the image is recorded.

A dark image with too little light is underexposed, a bright image with too much light is overexposed and an image with enough light is evenly exposed. A camera has four variables that can be changed to alter its exposure: EI, shutter angle, aperture and by using neutral density filters.

Let’s start with the EI, or exposure index setting - a good base setting to start with. This can be referred to using different metrics such as ISO, ASA, gain or EI depending on the camera, but the concept is the same. It’s a measurement of a film or camera sensor’s sensitivity to light.

The lower the value the less sensitive it is to light and the darker an image will be. Raising this value means the sensor is more sensitive to light and the brightness of an image will increase.

Most professional digital cinema cameras have what is called a ‘base’ or ‘native’ EI setting where the sensor performs best and has the most dynamic range and lowest noise. For example the Alexa sensor has a native EI of 800.

While EI can be changed on digital cameras, when using film its speed or sensitivity to light is set at a fixed level, such as 50 ASA, and cannot be altered without changing to a different kind of film stock.

The next exposure setting we can manipulate is the shutter angle or shutter speed.

A shutter is a solid layer in front of the sensor that opens and closes rapidly. When it opens it lets in light, when it closes it blocks light. The longer the shutter is open for the more light it lets in and the brighter an image is, while the shorter the shutter remains open, the less light it lets in and the darker an image is.

Cinema cameras use shutter angle and show a measurement in degrees. A large shutter angle means that more degrees of the circular shutter is open and more light is let in. While a smaller shutter angle, with a smaller opening, lets in less light.

Consumer or still photography cameras use shutter speed that shows this metric in fractions, such as 1/50th of a second - a measurement of how long the shutter is open for. So, fractions, such as 1/250th of a second means that the shutter is open for a shorter time and that less light will be let in, whereas fractions such as 1/25th of a second means the shutter is open for longer which lets in more light - resulting in a brighter image.

With these two settings done, we now move to the lens where we can set the aperture, iris or stop.

This is the size of the hole at the back of the lens that allows light to pass through it. Iris blades can either be expanded to open up the hole and let in more light, or contracted to make the hole that light passes through smaller.

On cinema lenses this is done manually by adjusting the barrel of the lens and on modern digital stills cameras it is usually adjusted via a button or scroll wheel on the camera which changes the iris of the lens internally. The aperture is either measured as a T-stop on cinema lenses or as an F-stop on stills lenses.

Whatever measurement is used, the lower the stop number the more light will be let through and the brighter an image will be. So a lens with a stop of T/2 has a large aperture opening and will let in much more light, while a lens with a stop of T/8 has a smaller opening and will let in less light.

These three settings, ISO, shutter speed and aperture are foundational to exposing footage and are called the ‘exposure triangle’.

In photography these three settings are regularly adjusted individually to find the right exposure, however in cinematography, more often than not these settings are made up front and only tweaked for their photographic effect.

For example in cinema, usually the ISO will be set to its native level, such as 800, the shutter will be set to 180 degrees or 1/50th of a second to ensure motion or movement feels ‘normal’, then the stop of the lens will be set depending on how much of the background the cinematographer wants in focus.

Opening up the aperture to a low number like T/1.3 means a shallow depth of field with much of the image out of focus, whereas stopping down to about T/8 will mean more of the image is in focus.

So if this is the case then how else do cinematographers adjust the brightness of an image?

They do it by manipulating the strength of the lighting and with the 4th exposure variable, neutral density, or ND, filters. These are pieces of darkened glass that can be put in front of the sensor or lens that decreases the amount of light that is let in without affecting the colour or characteristics of the image.

In film, a number is ascribed to a filter to show how many stops of light it blocks. Each stop is represented by 0.3. So ND 0.3 means 1 stop of light is blocked and ND 0.9 takes away 3 stops of light.

Many modern cinema cameras have ND filters built into the camera which can be adjusted internally via a setting. ND filters can also be used as physical glass filters that are mounted onto the front of the lens using a tray in a mattebox, or with a screw in filter on stills lenses.

COLOUR SETTINGS

Now that we know the 4 variable settings that we can use to adjust the brightness of an image in camera, let's look at another very important setting related to colour - white balance.

White balance, or colour temperature, is measured in Kelvin and changes how warm or cool an image looks.

The two most common white balance settings are 3,200K (or tungsten) and 5,600K (or daylight). This is because when you set the camera’s white balance to 3,200K and light an actor with a warmer, tungsten light the colour will appear neutral - not overly cool or warm.

Likewise when you set the camera to 5,600K and shoot with a cooler daylight fixture or outside in natural sunlight the image will also appear neutral.

This means that the lower you set the Kelvin value of the white balance the cooler an image will appear. So if you shoot outside in natural sunlight and set the camera to 3,200K then the image will be blue. Inversely if you shoot in tungsten light with a colour temperature of 5,600K then the image will be warm.

As well as having these two preset colour temperatures, most modern cameras also allow you to pick from a range of colour temperatures on the Kelvin scale and even have an auto white balance setting which automatically picks a Kelvin value to give the image a neutral colour balance.

It should also be noted that like with EI, when shooting on film the colour temperature is fixed to either daylight or tungsten and cannot be changed without using a different film stock.

MOTION SETTINGS

Finally, let's take a look at a camera setting that only applies to moving images - frame rate. To understand what frame rate is we need to think of film not as a video clip, but rather as a series of individual images.

When shooting on film, 24 still pictures are captured every second. Each of these pictures is called a frame. To create the illusion of a moving image these pictures are then projected back at a speed of 24 frames per second. You can think of it kind of like leafing through still images in a flip book at a speed of 24 pages every second.

Therefore, recording a frame rate of 24, or 25, frames per second with a camera produces the illusion of motion at a speed which is the same as that which we experience in real life.

Frame rate can also be used to exaggerate motion for effect by keeping the same playback ‘base’ frame rate of 24 frames per second and adjusting the frame rate setting that the camera captures.

For example if we want slow motion, we can set the camera to record 48 frames per second and then play it back at 24 frames per second. This results in twice as many frames and therefore a feeling of motion that is half as slow as that of real life.

Something important to note is that frame rate also affects exposure. Doubling the frame rate - for example from 24 to 48 frames per second - means that the camera loses a stop of light and will therefore be darker.

CONCLUSION

So, there we go: EI, shutter angle, aperture, ND, white balance and frame rate - six camera variables that every photographer or cinematographer needs to know.

If this all seems like too much technical information, the easiest way to practically get this information in your head is to find a digital camera and start experimenting with settings by shooting.

The more you practice with a camera, the more all of this information will start to become second nature. Until you get to a point where you can manipulate all of these settings unconsciously to capture that imaginative image that you see in your head.

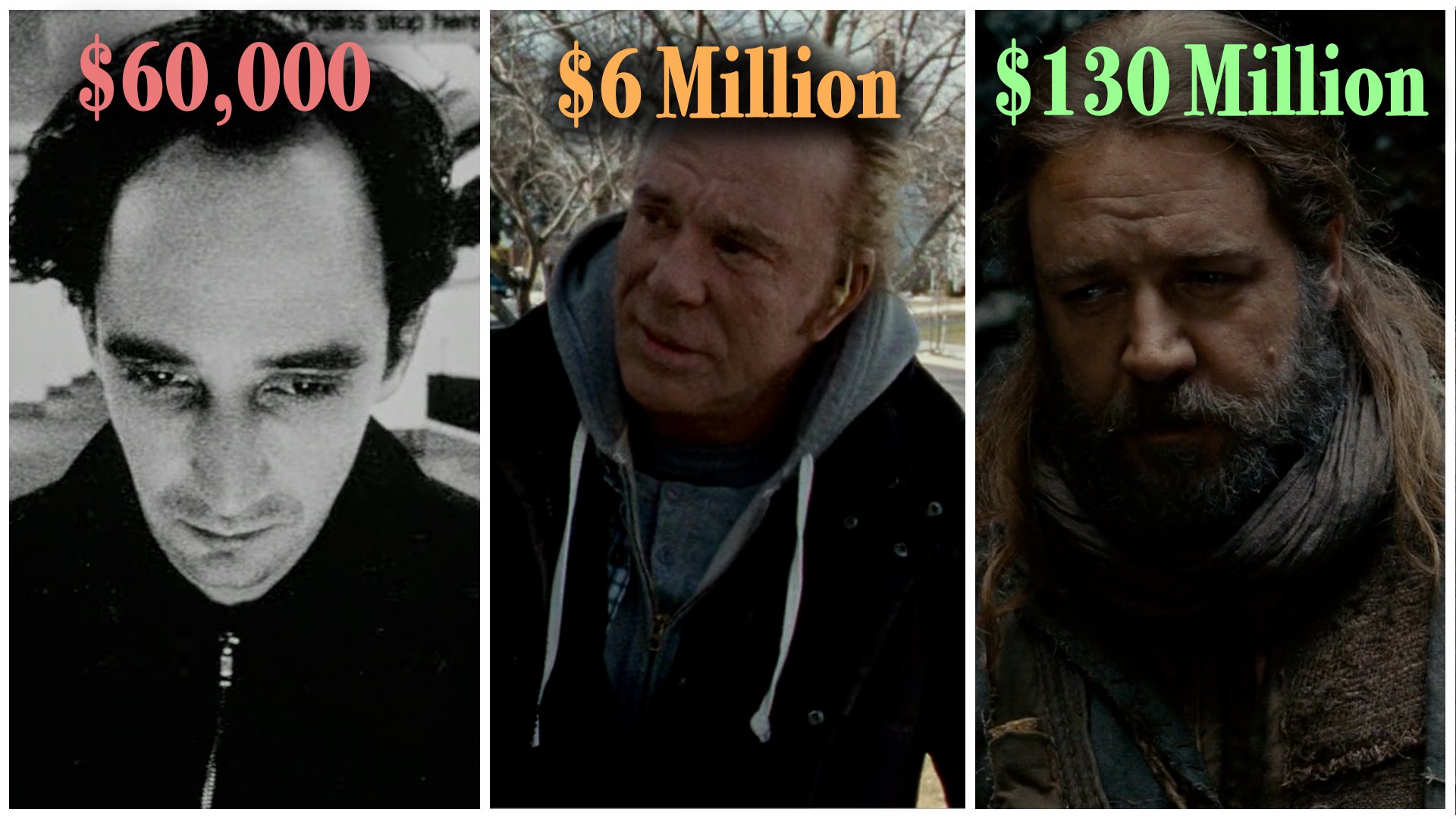

How Paul Thomas Anderson Shoots A Film At 3 Budget Levels

Let's take a look at three films made at three different budget levels from director Paul Thomas Anderson in order to get a sense of the trajectory of his career, his approach to filmmaking and how some of his methods of production have both remained the same and slowly shifted throughout his career.

INTRODUCTION

Compelling, flawed characters. Ensemble casts. Masterfully chaotic stories rooted in universal themes. Visual innovation. Technical competence. An overall strong vision and auteur-like control. These are some of the characteristics that, in my mind, make Paul Thomas Anderson one of, if not the best, director of the last 20 or so years.

Before we get started I think it is important to note that usually in this series I tend to feature directors who have undergone a greater change in the level of budget that they work with.

With the exception of his early work, Anderson has mainly stuck to producing work around the $25 to $40 million range and has never ventured into the realm of studio blockbusters. Nevertheless, let’s take a look at three projects which have been made at increasing budget levels: Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Licorice Pizza.

In doing this I hope to give a sense of the trajectory of his career, his approach to filmmaking and how some of his methods of production have both remained the same and slowly shifted throughout his career.

HARD EIGHT

“I was way too young to be given the keys to the car I think. I wrote it because I had to because it just came out.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

Anderson’s interest in making films began in his childhood in the San Fernando Valley and continued throughout his teenage years. He would write, direct and then film his ideas for shorts with his father’s Betamax video camera. He attended Santa Monica College but quickly became disillusioned with film school when he felt his ideas and experimentation were discouraged and filmmaking was turned into homework or a chore.

Instead he started working as a production assistant on sets in LA and managed to cobble together $10,000 from a combination of money for college, gambling winnings and his girlfriend’s credit card to produce the short film Cigarettes & Coffee.

He managed to cast Philip Baker Hall, an actor he greatly admired due to his work on Secret Honor - a film made by one of his greatest influences, director Robert Altman.

“Yeah it was based on stuff. I’d been working in Reno. I’d spent some time up in Reno and I was coming off experiences there of watching old guys. I loved this actor named Phillip Baker Hall, still love him and I heard his voice as the character. I just started writing and that’s what came out.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

He would continue this writing process throughout his career. Many of the films he would write were based on life experiences he had and set in locations that he would frequent or had lived in.

He took these experiences and places and created narrative arcs and settings with them. At the same time he often filled in the characters based on actors that he wanted to work with and wrote the roles with certain actors in mind.

Cigarettes & Coffee did very well. It got into the Sundance Short programme. When Anderson decided to turn it into a feature length film he also got into the Sundance programme in order to develop it.

It was there that he secured funding for the feature version, titled Sydney, through Rysher Entertainment all while in his early 20s. He was so young that some crew members on the set initially mistook him for a production assistant instead of the director.

“You know I just bluffed my way through directing. You gotta understand that at that time probably based on the success of Pulp Fiction and a couple other small independent films there was a lot of cash floating around from these cable companies. So if you could make a movie for under $2 million they could kinda sell it off piece by piece with just enough genre elements and a couple cast names and you could just go make your movie.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

So, with an independently funded $2 million low budget he set out to make the film by squeezing the production window into a narrow 28 days.

He cast the film by scooping up some well known actors on the tight budget and shot it all on location.

Due to the tight schedule they had loads to shoot, particularly for the casino scenes which they had to squeeze into night shoots from 10pm to around 8am the next morning.

To shoot a lot in the small window it helped that Anderson always had a very clear idea, visually, of how he wanted to capture the film, and no time was wasted with extraneous shots or deliberation.

To execute the cinematography he hired Robert Elswit, who at the time was probably the biggest name crew member on the project. They quickly found that they complimented each other and had similar visual sensibilities.

“Paul doesn’t need a lot of help in certain areas. I understand his taste, maybe so it’s never a surprise. I can anticipate what he wants to do for the most part. He always has a visual style before he starts. Always. I mean it changes to some extent but it’s completely thought out. Nobody is more prepared. Nobody has really thought through pictorial style as completely as Paul.” - Robert Elswit, Cinematographer

This style included explorative camera movement - often done on a Steadicam - and slow dolly tracking. Elswit lit with moderate contrast ratios, exposed the actors well and used hard light in a naturalistic way.

Even though both loved the look of anamorphic lenses, the producers prohibited it due to budgetary reasons. As a compromise they shot Super 35 Kodak film stock with Panavision cameras and lenses in a 2.39:1 aspect ratio - an aspect ratio he would often use in his later films.

Rather than giving loads of direction to performances, or ‘manipulation’ as he called it, he tried to instil the feeling of what he wanted to the actors before production and cast all the parts exactly as he wanted them. As the cliche goes - most of acting is about casting.

When it came to editing he worked with a similar methodology. He doesn’t like cutting everything up too much and instead prefers to keep the performances intact and pull from limited takes.

When he submitted his first two and a half hour cut of the film, friction between him and the production company ignited over final cut. Rysher Entertainment cut it down, changed the music, titles and even the name of the film to Hard Eight.

As a final compromise, the company said they would be happy to release Anderson’s version of the film if he came up with the funds himself in order to finish it. So, he used all the money he had from a recent deal he had signed for his next film Boogie Nights to finance post production and cut it the way he wanted to -and agreed to give up his original title Sydney.

Paul Thomas Anderson used the modest budget to secure a solid cast of big name actors to draw in an audience, produced the relatively small scope story over a limited 28 day production window, saved money on production design and by shooting Super 35 with an experienced DP, and eventually won out the creative battle for final cut.

BOOGIE NIGHTS

“I went into my next situation thinking that the lesson I learned was to be paranoid, protective and don’t trust anyone. Fortunately I got to work with a great studio and a guy named Mike De Luca who was able to see what I’d gone through and said ‘No, no. Trust me and put your faith in me.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

Let’s backtrack a bit. Anderson first came up with the idea for his second film Boogie Nights when he was 18. He wrote and directed ‘The Dirk Diggler Story’, a 30 minute mockumentary about the golden age of porn.

“After I made the short film I wrote as a sort of full length documentary taking a kind of Spinal Tap approach, you know. But by the time I’d finished that, that format had kind of been worn out and done many times. I just kinda figured the way to do this is to go nuts and just make it straight narrative. I eventually had a shooting script of 186 pages.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

The eventual script looked at the rise and fall of a character in the 1970s porn scene and examined the idea of addiction, ego, surrogate families and communities.

Like Hard Eight, he wrote the script with certain actors in mind - including performers that he had worked with prior on Hard Eight. And set it in the San Fernando Valley, an area he had grown up with and was familiar with. It featured an ensemble cast, inspired by the work of Robert Altman.

“Casting and writing are kind of the same thing. Because I write parts for actors that are my friends or actors that I don’t know that I really want to work with.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

With a buzz starting to go around about the script and while in post production on his first film, New Line Cinema came on board to produce with a $15 Million budget and promised a more hands off approach.

As it was a lengthy script that was larger in scope and needed the casting of many well known actors, the budget increase was still a bit stretched. After their positive experience on Hard Eight, Elswit was again hired as his DP.

Elswit remarked that from the first location scout Anderson would outline the kind of shots he wanted. That detailed level of specificity helped them to save time and money, since it was a lengthy, ambitious film for its budget level.

This vision was also important when coordinating and communicating some of the complex long takes that Anderson had in mind. The most famous of which was probably the opening shot of the film, where a Steadicam operator started on a ride on crane, which boomed down, gave the operator a chance to step off and then track characters into an interior - introducing the audience to the space and world of the film in the first 3 minutes.

“These long, complicated tracking shots are really fun to do. I think the actors love them. Movie acting is sort of so pieced up and chopped up. Very rarely is action called and 3 or four minutes later their scene happens. It’s just kind of fun for them to really act something through and let it breathe. Let it happen.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

Due to the arduous nature of the shot the main steadicam operator Andy Shuttleworth had a backup Steadicam operator as they had scheduled doing this 1 shot over an entire night.

Eslwit lit the exterior scene with two strong, hard backlights and some smaller units which were meant to mimic street lights which were metered at a stop of T2.8. Inside the club his team rigged the lowest budget 70s-style disco lights they could find overhead to keep all film lights out of the shot. This was brighter at T/4.

To maintain an even exposure across the different lighting levels Elswit used a wireless iris motor to slowly move the aperture remotely, going from T/ 2.8 outside to T/ 4 as the camera moved inside.

This time they had the budget to shoot with anamorphic lenses. They used Panavision C-series and pretty much shot the entire film with 3 lenses. A 40mm and 50mm for wider frames and a 75mm for close ups.

Anderson disliked heavy film grain so they shot on Eastman 100T 35mm film stock - the slowest practical speed stock they could find.

Like on Hard Eight Elswit liked to observe the natural light and then augment it with additional fixtures. To do this he would take stills on slide film during location recces, which had a limited dynamic range and therefore clearly showed what the natural light was doing.

He’d then come in and accentuate the natural light by, for example, using large tungsten lights through windows for day interiors to mimic sunlight.

Overall, the budget was spent on a large ensemble cast, re-creating the 1970s period scenes in the film, over a longer production schedule with many scenes in a long script which were shot innovatively with more extensive technical gear.

LICORICE PIZZA

After a career of producing almost non-stop critically acclaimed work Anderson turned to the 70s and, again, the San Fernando Valley for his next idea.

“I had a story that wasn’t exactly mine but that paralleled mine. My relationship with Gary Goetzman, who I don’t know if many of you know is a producer. Gary worked in the Valley. He was a child actor. When that didn’t really work out he started a waterbed business. The stories he told was an opportunity to enter into a world that I remember very well.” - Paul Thomas Anderson

Again, his script pulled from his own experiences, in a setting he was familiar with, with dialogue and characters written for specific actors, or first time actors, that he had in mind.

Having worked many times with Phillip Seymour Hoffman in the past, he turned to his son to play the role, who, although it was his first film, gave a more realistic, understated performance than Anderson saw in the other castings.

This was paired with an on screen chemistry with another first time actor, Alana Haim, who Anderson had shot music videos for in the past.

The long screenplay with its many scenes meant he needed a budget of around $40 million - which was supplied by MGM.

In the build up to the film Anderson decided to shoot lots of tests - partly to find a look for the film and partly to see if his two leads had enough on screen chemistry for the movie to work. This was a luxury that the higher budget afforded him - compared to Hard Eight that had to be shot in 28 days.

During these tests they also looked at different lenses and pushing and pulling different film stocks until they settled on the look they were happy with.

After parting ways with Elswit after many films together, Anderson had developed an unusual way of working without a dedicated cinematographer.

He, along with key technical crew members, such as his Gaffer Michael Bauman, camera operator Colin Anderson and key grip Jeff Kunkel all put their skills into a giant pot and shot a project without having a director of photography as a department head.

This worked due to the director’s technical prowess and track record with his experienced team of collaborators. This was first done on Phantom Thread, which they shot in the UK and repeated on various music videos.

However, when it came to shooting in the US they needed to have an officially credited DP due to union requirements. So, Anderson and Bauman shared the official credit of cinematographer while they continued working in the same collaborative style as before, with Anderson providing a visual direction and his key crew offering their input and technical execution.

“Because we’re shooting in California you’re kind of required to have someone listed as the cinematographer versus when we were overseas…The workflow is a very collaborative environment. He and I kinda worked very closely with Colin Anderson who is the camera operator. You know, they’ll formulate a shot, the two of them will, and he and I will have done preliminary scouting and talk about the lighting and then on the day we’ll execute what the plan is.” - Michael Bauman, Gaffer & Cinematographer

Like with many of his films, they mainly shot on vintage C-series anamorphic lenses from the 70s. After doing extensive tests they chose a set of Cs which included three different 50mm lenses each with different characteristics which they picked from depending on the situation or shot.

Anderson has always been passionate about not only shooting on film but even screening the dailies, the raw footage, projected using 35mm.

“One of the things that we do is that we do film dailies. We watch dailies while we are shooting. On set we have a space that we work out of that we can project film. It’s me, it’s the camera department, the core team of the camera department basically department heads would come in and out. We use that process to figure out takes we’re going to use.” - Andy Jurgensen, Editor

Overall, Licorice Pizza’s larger budget offered the director more time and resources to fine tune his vision by doing extensive camera tests, location scouting and tests with actors before stepping onto set. This resulted in a final film which utilised extensive shots with vast period correct backgrounds, shot with a curated selection of technical gear, stunts, and an ensemble cast which included some big name performers.

CONCLUSION

Certain aspects of Paul Thomas Anderon’s way of working as a director have remained consistent throughout his career, such as: writing scripts based on his personal experiences with ensemble casts which are ratcheted up by chaotic actions, shooting on 35mm film, often with anamorphic lenses, working with a small, consistent crew, focusing largely on casting and then letting actors do their thing, and creating innovative visual languages based on camera movement.

However, the more established he has become, the more he has also been able to take his time to create the films, with more extended production schedules and more time for testing and finding the look before production begins.

After the departure of Elswit, his methodology has also shifted away from the traditional route of working with a credited cinematographer, to a collaborative working style where he leans on the expertise of his crew department heads.

Despite these changes, his films always have a recognisable tone and style that ties them together despite the genre, script or subject matter of the film.

Cinematography Style: Barry Ackroyd

Barry Ackroyd is a cinematographer who plays to his strengths. Over his career he’s developed an instantly recognisable style to his photography that is based around a vérité, documentary-esque search for truth and capturing realism. In this episode of Cinematography Style I’m going to take a look at the renowned work of Barry Ackroyd by going over his philosophical ideas on cinematography and outlining the gear that he uses to execute his vision.

INTRODUCTION

Barry Ackroyd is a cinematographer who plays to his strengths. Over his career he’s developed an instantly recognisable style to his photography that is based around a vérité, documentary-esque search for truth and capturing realism.

He works with multiple on-the-ground, handheld, reactive cameras that use bold, punch-in zooms and has been hired by directors such as Ken Loach and Paul Greengrass that highly value a sense of realism and heightened naturalism in their films.

So, in this episode of Cinematography Style I’m going to take a look at the renowned work of Barry Ackroyd by going over his philosophical ideas on cinematography and outlining the gear that he uses to execute his vision.

BACKGROUND

“I’m a cinematographer who was brought up in documentaries in Britain on small budgets.”

Ackroyd’s initial plans to become a sculptor changed while he was studying Fine Arts at Portsmouth Polytechnic after he discovered the medium of 16mm film.

He began working as a television cameraman in the 1980s, mainly shooting documentaries. It was there that he first encountered director Ken Loach. After working on a couple of documentaries together, Ackroyd was offered an opportunity to shoot Riff-Raff for Loach - his first feature length fiction film.

He continued to shoot numerous fiction films and documentaries for Loach during this period, culminating in The Wind That Shakes The Barley which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival. Following this success he began working on other fiction projects for various well known directors such as: Paul Greengrass, Kathryn Bigelow and Adam McKay.

PHILOSOPHY

“Sometimes it’s better just to play to your strengths rather than to try to diversify too much…That was a choice I made, to play to my strengths.”

One of those strengths is a look rooted in a documentary style of working - which was informed by his early work on TV docs. Those documentaries relied on usually operating the camera handheld from the shoulder, in order to record the necessary moments as they happened live. In the real world events or moments often only happen once so you need an easily mobile camera to observe and capture them.

This is the opposite of fiction filmmaking, where events and scenes can be played out multiple times, and are more often than not photographed in a carefully curated, composed visual style. Rather than going the usual fiction cinematic route, Ackroyd took documentary conventions and ways of working and applied them to fiction filmmaking.

For example, he prefers always shooting movies on real locations whenever possible, over shooting them on a constructed set or in a soundstage - even if that real location is a ship on the ocean.

Ackroyd tends to steer away from setting things up too perfectly and instead leans towards a look where capturing a version of reality is far more important than capturing a ‘perfect’ image.

“I think if you look at my work I’m always trying to push what I’ve done before…and actually I push it towards imperfection…There’s a kind of state that you get into where you’re just in tune with what’s happening in front of the camera.”

To capture images realistically, honestly and with as few barriers as possible he relies on working with multiple camera operators and puts a lot of trust in his crew members. He gives his crew lots of credit on set and in interviews, from the focus puller to the sound recordist, and maintains the importance of teamwork and a group effort in creating a film.

“I used to say that in documentaries the best shot that you get in documentaries is out of focus and underlit and looks rubbish. You know that it had to be in the film because it was absolutely right at the time…I think that’s what you’re striving for, you know. Not to overwhelm people with the beauty. Not to fall in love with the landscape…But to get the picture that…you’re involved with it.”

An example of how he seeks authenticity through imperfections can be found in his approach to blocking scenes with directors and actors. Usually actors rehearse a scene on set and then marks are put down on the floor to indicate the exact position that actors must stand in in order to be perfectly lit, perfectly framed and perfectly angled for the shot.

Ackroyd prefers not to mark actors. He sets up any lights he needs either overhead or outside the set so that the actors have the freedom to move around as they like when they play out the scene. Since they don’t have to worry about hitting specific marks, he finds that the actors loosen up more, which injects a realist spontaneity into how their performances are captured.

Sometimes this leads to technical imperfections like moments that are out of focus or frames that aren’t classically composed. But it also injects an energy into the images which is undeniable.

GEAR

“You know I like to get physically involved. We ran around with the cameras. We had four or five cameras at times…In any one setup you’re trying to talk to all the guys, see what they’ve done, see what the next shot should be and give, you know, support and advice.”

As we mentioned, Ackroyd likes shooting with multiple handheld cameras. This allows his operators to quickly react and capture details or moments of performance. It also provides the director and the editor with multiple angles and perspectives which they can cut to in order to build up the intensity and pacing in a scene.

Directors who he has repeatedly collaborated with like Paul Greengrass and Kathryn Bigelow are known for their preference for quick cutting. Ackroyd’s style provides them with the high number of angles that are needed to work in this way.

One of the most important camera tools he uses is focus. He describes focus as being the best cinematic tool, even better than a dolly, crane or tripod, because focus mimics what we naturally do with our eyes and can be used to shift the attention of the audience to a particular part of the frame. He isn’t overly strict with his focus pullers and in fact prefers the natural, more organic method where people drift in and out of focus over every single shot having perfectly timed, measured and calculated focus pulls.

Another important tool in his toolbox is his use of zoom lenses. Again this goes against traditional fiction cinematography principles which ascribe a greater value to prime lenses over zooms - which most documentaries are shot with. He uses quick punch-in zooms as a tool to direct the focus of the audience in the moment. For example if a line of dialogue or an energetic moment of performance is particularly important his operators may push into it with a quick zoom for emphasis.

His choice of camera gear is a bit mishmash. In the same film he may use different formats, such as digital, 35mm and 16mm film, with different prime and, of course, zoom lenses. For example Captain Phillips involved shooting aerial shots digitally, while sequences in the fishing village and on the skiff were shot in Super 16, which they then switched to 35mm film once the characters boarded the large shipping vessel.

He likes the texture of film and has often used the higher grain 16mm to compliment his look. He famously used Super 16 to support the raw, on-the-ground documentary aesthetic on The Hurt Locker.

“Well then I thought it has to be Super 16. We have to get back to the basics. Get down to the lenses you can carry and run with and will give you this fantastic range of wide shots and big close ups…The first thing everybody said was that, ‘well, the quality is not going to be good.’ Well, nobody has criticised the quality of the film. They’ve only praised it.”

He has a preference for Fujifilm stock as it fares well in high contrast lighting situations. When shooting on film he would sometimes purposefully underexpose the negative and then bring up the levels later in the DI in order to introduce more grain to the image.

Ackroyd liked to combine 250D and 500T Fujifilm stocks when shooting Super 16 or 35mm. However, after Fujifilm was discontinued and no longer available he transitioned to shooting on Kodak film or with digital cameras - mainly the Arri Alexa Mini.

On Detroit he used the Arri Alexa Mini in Super 16 mode and shot with Super 16 lenses to introduce noise and grain to the image and get a Super 16 feel, which was further amped up in the grade, all while maintaining the benefits of a digital production.

The Aaton XTR is his go to Super 16 camera, so much so that he owns one. He has used different 35mm cameras such as the Aaton Penelope, the Arriflex 235, the Moviecam Compact and the Arricam LT. Some of his favourite Super 35 zooms are the 15-40mm and, in particular the 28-76mm Angenieux Optimo zoom, which are both light enough to be handheld and provide a nice zoom range that he can use to punch-in with.

He’s also used the Angenieux Optimo 24-290mm, sometimes with a doubler when he needs a longer zoom. It’s too heavy to be used handheld but he has used it with a monopod to aid in operating the huge chunk of a lens and still preserve a handheld feel. Some other zooms he has used include a rehoused Nikon 80-200mm and the Canon 10.6-180mm Super 16 zoom.

Although he prefers zooms he often carries a set of primes which have a faster stop and can be used in low light situations such as Zeiss Super Speeds or Cooke S4s.

Due to the lack of blocking or focus marks, he usually gives his focus pullers a generous, deep stop to work with of around T/5.6 and a half.

To further support his look based on realism and documentary, he lights in a very naturalistic manner. He tries to refrain from lighting exteriors all together and for interiors adds touches of artificial light which are motivated when he needs to balance the exposure in a scene. A lighting tool that he likes to use for this are single Kino Flo tubes, which can easily be rigged overhead or out of sight to provide a low level fill to a scene.

CONCLUSION

Barry Ackroyd’s cinematography is more about deconstructing photography than it is about trying to produce a perfectly beautiful image.

To him imperfections are a signal of authenticity and an expression of realism rather than a flaw. Breaking down an image can’t be done competently without a great degree of skill and knowledge.

His film’s aren’t created by just picking up a bunch of cameras and pointing them in the general direction of the action, but are rather made through deliberate thought and cultivation of a style that emits as much intensity, feeling of reality and truth as possible.

Does Sensor Size Matter?

Since there are loads of different cameras with loads of different formats and sensor sizes out there to choose from, in this video I’ll try to simplify it a bit by going over the five most common motion picture formats and discussing the effect that different sensor sizes have on an image.

INTRODUCTION

The sensor or film plane of a camera is the area that light hits to record an image. The size of this area can vary a lot depending on the camera, with each sensor size or format having a subtly different look.

Since there are loads of different cameras with loads of different formats and sensor sizes out there to choose from, in this video I’ll try to simplify it a bit by going over the five most common motion picture formats and discussing the effect that different sensor sizes have on an image.

5 MOTION PICTURE FORMATS

The size of a video camera's film plane or sensor ranges all the way from the minuscule one third inch sensor found in smartphones or old camcorders up to the massive 70x52mm 15-perf Imax film negative. But, rather than going over every single sensor in existence, I’m going to take a look at five formats which are far and above the most popular sizes used in film production today and have been standardised throughout film history.

While there are smaller sizes like 8mm film or sizes in between like the Blackmagic 4K’s four third sensor, these sizes are used far less frequently in professional film production and are an outlier rather than a standard. I’ll also only be looking at video formats so won’t be going over any photographic image sizes such as 6x6 medium format.

The smallest regularly used format is Super 16. The film’s smaller size of around 7.4 by 12.5mm makes it a cheaper option than the larger gauge 35mm, as less physical film stock is required.

Due to this it was often used in the past to capture lower budget productions. Now that digital has overtaken film, Super 16 is mainly chosen for its optical capabilities. Its lower resolution look and prominent film grain means that it is often used today to evoke a rough, documentary-esque feeling of nostalgia.

Some digital cameras, such as the original Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera have a sensor that covers a similar area to Super 16 and cameras such as the Arri Alexa Mini have specialised recording modes which only samples a Super 16 size area of the sensor.

Moving up, the next, and by far the most common format is Super 35. This format is based on the size of 35mm motion picture film that covers an approximate area of 21.9 by 18.6mm. 35mm refers to the total width of the frame, including the perforated edges on either side of the negative area.

Depending on the budget, aspect ratio, and lenses different amounts of horizontal space, measured in perforations, can be shot. The frame can be cropped to use less film stock or to extract a widescreen image when using spherical lenses. Shooting with anamorphic lenses, that optically squeeze the image, requires using the entire area of the negative or sensor and then de-squeezing the image at a later stage to get to a 2.39:1 aspect ratio.

Many digital cinema camera sensors are modelled on this size, with some minor size variations depending on the camera, such as the Arri Alexa Mini, the Red Dragon S35 and the Sony F65. Since this format is the most popular in cinema, most cinema lenses are designed to cover a Super 35 size sensor. Meaning this format has the widest selection of cinema glass available on the market.

Stepping up from 35mm we get to what is called a large format or a full-frame sensor. This size is modelled on still photography DSLR cameras with a 35mm image sensor format, such as the Canon 5D that is larger than Super 35. It’s also around the same size as 8-perf Vista Vision film.

Although digital sensors differ a bit depending on the camera, it is usually about 36 by 24mm. Some cameras with this sensor size include the Alexa LF, the Sony Venice and the Canon C700 FF.

This large format is a middle ground between Super 35 and the next format up - 65mm.

Originally, this format was based on using 65mm gauge film which was 3.5 times as large as standard 35mm, and measured 52.6 by 23mm using 5 vertical perforations with a widescreen aspect ratio of 2.2:1. The Alexa 65 has a digital sensor that matches 65mm film and is a viable digital version of this format.

Finally, the largest possible motion picture format that you can shoot is Imax film. With an enormous 15 perforations, an Imax frame covers a 70.4 by 52.6mm image area.

Due to its enormous negative size and the large, specialised cameras required to shoot it, this format is prohibitively expensive and out of the budget range of most productions. But, it has seen a bit of a resurgence in recent years on high budget blockbusters from directors such as Christopher Nolan who champion the super high fidelity film format.

THE EFFECTS OF SENSOR SIZES

With these five formats in mind, let’s examine some of the effects and differences between them. There are a few things that choosing a format or sensor size affects.

The most noticeable optical effect is that different formats have different fields of view. What this means is that if you put the same 35mm lens on a Super 16, Super 35 and a large format sensor camera, the smaller the sensor is the tighter the image that is recorded will appear.

So the field of view on a large format camera will be much wider than on a Super 16 camera which is tighter. Since the field of view is wider, larger formats also have a different feeling of depth and perspective.

Because of this difference, the sensor determines the range of focal length lenses that need to be used on the camera. To compensate for the field of view differences, smaller formats like Super 16 need to use wider angle lenses to get to an image that sees the same amount of information, while larger formats need to use longer lenses for that same frame.

For example, to get the same field of view from a 35mm lens on a Super 35 sensor, a Super 16 camera needs to use a 17.5mm focal length and a large format, full-frame camera needs to use a 50mm focal length.

Since focal lengths affect the depth of field an image has, this is another effect of different formats. Longer focal lengths have a very shallow depth of field or area of the image which is in focus. So full-frame cameras that use longer focal lengths will therefore have a shallower depth of field. This means that the larger the format, the more the background will be out of focus and the more the subject will be separated from the background.

This is helpful for creating a greater feeling of depth for wide shots which people often perceive as looking more ‘cinematic’.

One negative effect of this is that the job of the 1st AC to keep the focus consistently sharp becomes far more difficult. For this reason smaller formats such as Super 16 are far more forgivable to focus pullers as they have a deeper depth of field where more of the image is in focus and therefore the margin for error is not as harsh.

The grain and resolution that an image has is also affected by the size of the format. The smaller the format is, the more noticeable the grain or noise texture will usually be, and the larger the sensor is the finer the grain will appear and the greater clarity and resolution it often has.

Sometimes cinematographers deliberately shoot smaller gauge formats like Super 16 to create a more textured image, while others prefer larger formats like 65mm for it’s super clean, sharp, low noise look.

So those are the main optical effects of choosing a format.

Smaller formats require wider focal lengths, have a deep depth of field, have more grain and will overall feel like they are a bit flatter.

Larger formats require longer focal lengths, have a shallower depth of field, less grain, greater resolution and clarity and overall have a more three-dimensional look with an increased feeling of depth.

There are also the all-important practical implications to be considered. Generally speaking the larger the format, the larger the form factor of the camera will be to house it and the more expensive it is to shoot on.

This calculation may be different when comparing the costs of digital and film, but when comparing all the digital formats, renting the cameras and lenses for 65mm will be more expensive than a Super 35 camera. Likewise, when comparing film formats 16mm is vastly cheaper than Imax.

So broadly speaking, smaller formats tend to be more budget friendly and come in a smaller housed package.

DOES SENSOR SIZE MATTER?

Coming back to the question of whether sensor size matters, I don’t think any one sensor is necessarily better than another. But the effects that they produce are certainly different.

Filmmakers that want an image that immerses an audience in a crystal clear, highly detailed, wide vista with a shallow depth of field will probably elect to shoot on a larger format.

Whereas those who require a more textural, nostalgic or rougher feeling photography with less separation between the subject and the background may be drawn to smaller gauge formats.

As always, the choice of what gear is most suitable comes down to the needs of the project and the type of cinematic tone and photographic style you are trying to capture.

Using Colour To Tell A Story In Film

Let’s examine this idea of colour by going through an introduction to colour theory, look at how filmmakers can create a specific colour palette for their footage and check out some examples of how colour has been used to aid the telling of different stories.

INTRODUCTION

Cinematography is all about light.

Light is a complex thing. It can be shaped, it can come in different qualities, different strengths and, importantly, it can take the form of different colours.

So, let’s examine this idea of colour by going through an introduction to colour theory, look at how filmmakers can create a specific colour palette for their footage and check out some examples of how colour has been used to aid the telling of different stories.

WHAT IS COLOUR THEORY?

Colour theory is a set of guidelines for colour mixing and the visual effects that using different colours has on an audience.

There are many different approaches to colour theory ranging from ideas all the way back in Aristotle’s time up to more contemporary studies on colour such as those by Isaac Newton. But let's just take a look at some basic ideas and see how they can be applied to film.

When different spectrums of light hit objects with different physical properties it produces a colour, which we put into a category and ascribe a name to.

Primary colours are a group of colours that can be mixed to form a range of other colours. In film these are often, but not always, used sparingly in a frame. A splash of red in an otherwise green landscape stands out and draws the eye.

An important part of colour theory in the visual arts space is knowing complimentary colours. When two of these colours are combined they make white, grey or black. When the spectrum of colours are placed on a colour wheel, complimentary colours always take up positions opposite each other.

When two complementary colours are placed next to each other they create the strongest contrast for those two colours and are generally viewed as visually pleasing. Cinematographers often combine complimentary colours for effect and to create increased contrast and separation between two planes in an image. For example, placing a character lit with an orange, tungsten light against a blue-ish teal background creates a greater feeling of separation and depth than if both the character and the background were similar shades of orange.

When it comes to the psychology of using colour, cinematographers generally fall into two camps - or somewhere in the middle. Some cinematographers such as Vittorio Storaro think that certain colours carry an innate, specific psychological meaning.

“Changing the colour temperature of a single light, changes completely the emotion that you have in your mind. I didn’t know at the time the meaning of the colour blue. It means freedom.” - Vittorio Storaro

Other filmmakers rely more on instinct and what feels best when lighting or creating a colour palette for a film. The psychology of colour can change depending on the context and background of the audience.

As well as being a means of representing and expressing different emotions, deliberate and repeated uses of colour can also be used by filmmakers as a motif to represent themes or ideas.

Another important part of colour theory is warm and cool colours. The Kelvin scale is a way of measuring the warmth of light, with lower Kelvin values being warmer and higher Kelvin values being cooler.

Warm and cool colours can have different psychological effects on an audience and can also be used to represent different physical, atmospheric conditions. Using warmer colours can be used to emphasise the feeling of physical heat in a story, while inversely cooler colours can be used to make the setting of a story feel cold or damp.

CREATING A COLOUR PALETTE

Now that we have a basic framework of colour theory to work with, let's look at the different ways that filmmakers can make a colour palette for a movie. Colour palettes in film can be created using three tools: production design and costume, lighting and in the colour grade.

The set and the clothing that the characters are dressed in is always the starting point for creating a colour palette. In pre-production, directors will usually meet with the production designer and come up with a plan for the look of the set. They might give the art director a limit to certain colours they need to work with, or decide on specific tones for key props. The art team will then go in and dress the set by doing things such as painting the walls a different colour and bringing in pieces of furniture, curtains and household items that conform to that palette.

Since characters are usually the focus of scenes and we often view them up close, choosing a colour for their costume will also have a significant impact on the overall palette. This may be a bold primary colour that makes them stand out in the frame, or something more neutral that makes them blend into the set.

With a set to work with, the next step in creating a movie’s colour palette is with lighting.

Traditionally, film lighting is based around the colour temperature of a light which as we mentioned could be warm, such as a 3,200K tungsten light or cool, such as a 5,600K HMI. On top of this, cinematographers can also choose to introduce a tint to get to other colours. This can be done the old school way by placing different coloured gels in front of lights, or the modern way by changing the hue or tint of LEDs.

DPs can either flood the entire image with monochromatic coloured light, or, as is more common, light different pockets of the image with different colour temperatures or hues. In the same way that we create contrast by having different areas of light and shadow in an image, we can create contrast by having different areas of coloured light.

Once the colour from the set and the lighting has now been baked into the footage, we move into post-production where it’s possible to fine tune this colour in the grade.

An image contains different levels of red, green and blue light. A colourist, often with the guidance of a director or cinematographer, uses grading software like Baselight or Da Vinci Resolve to manipulate the levels of red, green and blue in an image.

They can change the RGB of specific values of light, like introducing blue into the shadows, or adding magenta to the highlights. They can also create power windows, to change the RGB values in a specific area of the frame, or key certain colours so that they can be individually adjusted. There are other significant adjustments they can make to colour such as determining the saturation or the overall intensity of the colour that the image has.

USING COLOUR TO TELL A STORY

“It’s a show about teenagers. Why not make a show for the teenagers that looks like how they imagine themselves. It’s not based on reality but mostly on how they perceive reality. I think colour comes into that pretty obviously.” - Marcell Rév

When coming up with a concept for the lighting in Euphoria, instead of assigning very specific psychological ideas to colour, Marcell Rév used colour more generally as a way to elevate scenes from reality.

He wanted to put the audience in the emotionally exaggerated minds of some of the characters and elevate the level of the emotions that were happening on screen. In the same way that the often reckless actions of the characters continuously ratcheted up the level of tension in the story, so too did the exaggerated, brash, coloured lighting.

To increase the potency of the visuals he often played with a limited palette of complementary colours. He avoided using a wide palette of colours, as it would become too visually scattered and decrease the potency of the colours that he did use.

Along with his gaffer he picked out gels, mainly light amber gels which he used with tungsten lights and cyan 30 or 60 gels which he used with daylight HMIs. They also used LED Skypanels, which they could quickly dial specific colour tints into.

“That light…that colour bouncing off the screen and arriving at us we don’t see it only with the eyes, we see it with the entire body…because light is energy. I’m sending some vibrations to you, to the camera, to the film…unconsciously.” - Vittorio Storaro

When photographing Apocalypse Now, Vittorio Storaro was very deliberate about his use of colour. He wanted the colours to be so strong and saturated that the world on film almost became surrealistic.

He wasn’t happy with Kodak’s 5247 100T film stock at the time, so he got the film laboratory to flash the negative to get the level of contrast and saturation which he was happy with.

In the jungle scenes he didn’t want to portray the location naturally. He sometimes used filters to add a monochromatic palette which was more aggressive, to increase the tension.

“I can use artificial colour in conflict with the colour of nature. I was using the symbolic way that the American army was using to indicate to the helicopter…They were using primary and complementary colours. I was using those kinds of smoke colours to create this conflict.” - Vittorio Storaro

He also described how the most important colour in the film was black, particularly in the silhouetted scenes with Kurtz. He felt black represented the unconscious and was most appropriate for scenes where the audience was trying to discover the true meaning of Kurtz, with small slithers of light, or truth, emerging from the depths of the unconscious.

What A Boom Operator Does On Set: Crew Breakdown

In this Crew Breakdown video I’ll go over the position in the sound department of the boom operator, to break down what they do, their average day on set and some tips which they use to be the best in their field.

INTRODUCTION

In this series I go behind the scenes and look at some of the different crew positions on movie sets and what each of these jobs entails. If you’ve ever watched any behind the scenes videos on filmmaking you’ve probably seen this person, holding this contraption.

In this Crew Breakdown video I’ll go over the position in the sound department of the boom operator, to break down what they do, their average day on set and some tips which they use to be the best in their field.

ROLE

The boom operator, boom swinger or first assistant sound is responsible for placing the microphone on a set in order to capture dialogue from the actors or any necessary sounds in a scene.

They do this by connecting a boom mic, or directional microphone, to a boom pole. The mic is then connected either with an XLR cable or wirelessly to a sound mixer where the sound intensity is adjusted to the correct level.

On feature films this mixing is done separately by the sound recordist who heads the department, and is responsible for recording all the audio and delegating the positioning of the mic to the boom operator. However, for low budget features, TV shoots, documentaries or commercials, the role of the sound recordist and the boom swinger is sometimes performed simultaneously by one person.

To get the best possible sound and capture dialogue clearly the microphone usually needs to be placed as close as possible to the actors. Since film frames have quite a lot of width to them and see a lot of the location the best way to get the microphone in close to the action without it entering the shot is to attach it to a boom pole, with the mic angled downwards and use the length of the boom held overhead to position the microphone directly above the actors and outside of the top of the frame.