How Denis Villeneuve Shoots A Film At 3 Budget Levels

Great directors are capable of creating and maintaining very deliberate cinematic tones. This is true of Denis Villeneuve.

INTRODUCTION

Great directors are capable of creating and maintaining very deliberate cinematic tones. This is true of Denis Villeneuve. His films are thrilling, dramatic and at times epic in both tone and scope, yet also provoke subtle political, ethical and philosophical questions that provide substance to action.

His career has wound a path from lower budget productions all the way to directing some of the largest blockbusters in the world.

In this video I’ll look at three of his films at three increasing budget levels, the low budget August 32nd on Earth, the medium budget Sicario and the high budget Dune to unveil the formation of his style and identity as a director.

AUGUST 32ND ON EARTH

The Canadian filmmaker’s interest in movies was piqued as a child. He began making short films when he was in high school, where he also developed an early love of science fiction. After leaving school he began studying science but later changed his focus to film when he moved to the University of Quebec.

After winning some awards he began working with the National Film Board of Canada where he established a working relationship with producer Roger Frappier who developed films by emerging directors.

The NFB funded his first 30 minute short film which showed a lot of promise. Frappier then produced Cosmos, a collection of six different shorts made by six young directors, which included Villeneuve as well as his future collaborator André Turpin. It was a critical success.

Following this Villeneuve wrote a screenplay with a contained story about a woman who is thrust into an existential crisis after surviving a car accident. Frappier came on board to produce the film under his production company Max Films.

André Turpin was brought on board to serve as the cinematographer on the film. This collaboration established a trait which would continue throughout his later movies - an openness to letting DPs bring their own photographic sensibilities to the project, while at the same time always firmly maintaining his own strong perspective on the script.

To August 32nd On Earth, Turpin brought his preference for strong, saturated 35mm Kodak colour, very soft side light, character focused framing and use of sharp lenses with a shallow depth of field. This was complemented by Villeneuve’s preferences for using subjective framing with lots of close ups and motivated, smooth camera moves from a tripod, dolly or Steadicam.

Although the film is a mature, cinematically grounded and more realistic production, it also has a dreamlike tone with moments of experimentation, some of which seems to have been inspired by his love of French New Wave Films, such as Breathless.

From the philosophical walk and talks, to the numerous jump cuts and even the main character's short haircut - Breathless seems to be a clear influence. And if you think maybe these are just coincidences, there’s even a shot with a poster of Seberg who starred in Breathless. While the influence of French New Wave filmmaking is strong, it’s not overpowering.

Villeneuve took parts of the style that worked effectively for a low budget film, such as a subjective focus on very few characters, and parts that suited his story, such as the experimental editing to visualise the character’s post accident haze, and combined it with own sensibilities for realism, mature drama, cinematic control, and isolated desert locations (which cropped up in much of his later work).

August 32nd established his strong voice as a director, his ability to maintain a consistent cinematic tone, openness to collaboration and his stylistic sensibilities.

He made his first low budget film by writing a simple story with few moving parts, using experimental cutting to avoid showing expensive set pieces like the car accident, and instead devoted his budget to creating a deliberate, cinematic camera language.

SICARIO ($30 Million)

August 32nd got into the Cannes Film festival and premiered in the Un Certain Regard section, which he followed with a string of Canadian medium budget films.

In 2013 it was announced that Villeneuve would direct Sicario, an action thriller on the Mexican border. He was drawn to the philosophical concept of the border, an imaginary line which divides two extremes, as well as examining the idea of western influence and how it is exerted by first world nations.

At a medium-high $30 million budget it was a step up from his prior Canadian films in the $6 Million range. However, the script involved many large, expensive set pieces and complex action sequences which meant the budget, relative to what needed to be shot, wasn’t huge. After writing or co-writing the screenplays for his early projects, Sicario was penned by Taylor Sheridan.

“The research I did after, as I was prepping the movie, just confirmed what was written in the script… I wanted to embrace Mexico. To see scenes from the victim’s point of view…try to create authenticity in front of the camera and not fall into cliches.”

To capture an authentic, naturalistic vision he turned to famed cinematographer Roger Deakins who he’d worked with before on Prisoners.

They storyboarded many of the sequences as a team during the process of location scouting in pre-production. This nailed down the photographic style they wanted and also allowed them to work quickly and effectively when shooting complex action sequences that needed to be pieced together.

This helped decrease shooting time in the tight schedule. Villeneuve’s clear vision for the shots he needed to get also saved time. For example, after shooting a master of a confrontation scene, Deakins asked if he should move the camera closer to get singles of each character. Villeneuve declined, knowing that he would use the master shot as a single long take in the edit…which he did. Not shooting extraneous close ups saved the production around three hours.

In his trademark style, Deakins shot many of the scenes from an Aerocrane jib arm with a Power Pod Classic remote head, a combination he’s used for over 20 years.

This allows him to quickly and easily move the camera on any axis, making it useful not only for smooth moves, but also for quickly repositioning the frame, allowing for a more organic working style and time saving setup.

“I mean the challenge of the photography of any film is sustaining the look and the atmosphere and not breaking out of that.”

One challenge when shooting out in Villeneuve’s favourite location, the desert, was controlling the natural light. Deakins did this by breaking down and scheduling each exterior shot at a specific time when the angle of sunlight was right with the assistant director Don Sparks.If the sun went away or into clouds they had a separate list of shots they could get such as car interiors or close ups which were easier to light.

Another way of exercising control of the lighting and the location was shooting certain interiors in a studio. To free up space for camera moves and to keep the light as motivated and as natural as possible he set up all his lights outside the set - 6 T12 fresnels pushing hard, sourcey light through windows and 65 2K space lights to provide ambience outside those windows.

He recorded on ArriRaw with the Alexa XT using Master Prime lenses - usually the 32, 35 and 40mm, occasionally pulling out the 27mm for wides.

“The overall approach to the film was this personal perspective. We’re either with Emily, or with Benicio, you know. So we took all that to say well we’ll do this whole night sequence from the perspective of the night vision system.”

To do this a special adapter was used on the Alexa to increase its sensitivity to light. He then lit the scene with a low power single source bounced from high up to mimic realistic moonlight and keep the audience immersed.

The much larger scope Sicario was therefore pulled off with a $30 million budget by: carefully planning out the complex action sequences in pre production to save time and money, casting famous leads that drew audiences to the cinema, shooting some interiors in a studio for increased control and exteriors on location to wrap the audience up in a feeling of authenticity and controlling the score, sound design and pacing in the edit to provide a consistently thrilling tone.

DUNE ($165 Million)

After Sicario’s critical and commercial success Villeneuve turned to a project he’d dreamt about making since he was a teenager - Dune - based on the sci fi novel by Frank Herbert.

“I felt in love spontaneously with it…There’s something about the journey of the main character…This feeling of isolation. The way he was struggling with the burden of his heritage. Family heritage, genetic heritage, political heritage.”

With this thematic backing Villeneuve took on this sci fi story of epic proportions with a large studio budget of around $165 million. Since a large part of the undertaking was based on creating his imaginings of the world of Dune, he teamed up with his regular production designer Patrice Vermette and experienced cinematographer Greig Fraser. Together they worked with the extensive conceptual art and storyboards to bring the story to life. Since the way in which the sets were constructed would have an impact on the lighting, Fraser had many pre-production meetings with Vermette about light.

“The main character in the movie for me is nature. I wanted the movie to look as naturalistic and as real as possible. To do so we used most of the time natural light.”

On Arrakis buildings are constructed from rock with few openings to save its occupants from the oppressive heat. So instead of using direct light, the interior lighting is soft and bounced. To create this Fraser and his gaffer rigged Chroma-Q Studio Force II LED light strips to simulate the ambient softness of bounced sunlight. For close ups where they needed more punch he used LED Digital Sputnik DS6 fixtures.

To create depth Fraser constantly broke up spaces by using areas of light and shadow in different planes of the image. To bring out the incredible heat and harshness on the desert planet, Fraser used hard natural light from the sun which he cut into sections of sharp shadow in interesting ways.

Generally in cinematography, the larger a space is the more expensive and work it takes to light. This sequence was no exception.

In a massive undertaking, Fraser’s grip and rigging team put up gigantic sections of fabric gobo over the set’s ceiling to creatively block the sunlight, to create a sense of ominous depth to the space. They then had a precise window to shoot the scene between 10:45 and 11:10am where the angle of the sun would be perfect.

They photographed Dune on large format with the Alexa LF and Mini LF on large format spherical Panavision H-series lenses to render the taller 1.43:1 Imax sequences and Panavision Ultra Vista 1.65x anamorphic lenses for the 2.39:1 shots.

“I wanted the sky to be a vivid white. A very harsh sky. To bring kind of a violence to the desert - a harshness to it.”

To do this Fraser got his colourist Dave Cole to create a LUT for the camera in pre-production that pulled out the blue in the image and rolled off the overexposure.

The final finishing of the movie in the grade involved an interesting process. Fraser felt the look of the film should be more on the digital side, with the slightest hint of film.

To do this they took the graded digital files and did a laser-recording-film-out, recording the digital image onto Kodak 5254 print film. This film was then scanned and converted back to digital files. The result was a final file with just a tiny hint of film grain and subtly organic film artefacts.

When it came to sound Villeneuve brought composer Hans Zimmer into the room with the sound design team, so that the two were married together to create the ultimate immersive experience.

Villeneuve successfully grounded Dune’s fantastical world with his trademark realism and used the massive budget to: pull off a long shoot with a big crew, enormous technical setups and set construction, access to any gear they needed and extensive VFX post-production work.

CONCLUSION

Villeneuve’s films are strung together by a thrilling subject matter with political and philosophical themes told in a grounded, realist visual style…and, well, the desert.He’s drawn to scripts that both immerse the audience in a riveting world and pose subtle thematic questions.

Throughout his career he has worked in a collaborative way with different in demand DPs who each imparted touches of their own style on the stories. However, his films are always very much his own and supported by his vision.

Villeneuve’s ability to control the tone of his films using every filmmaking element, from the script to the camera work, the edit and the music, is what has elevated his work to its critical and commercial heights.

How Movies Are Shot On Film In The Digital Era

In this video I thought I’d do a bit of a deep dive into why some productions still choose to shoot on film over using digital cameras and outline the whole process of how film is shot, from pre-production and production all the way to it’s post production workflow.

INTRODUCTION

Although there was a time when many thought that shooting on motion picture film stock would quickly die out after the launch of high quality digital cinema cameras like the Arri Alexa in 2010, film still persists. In fact in recent years it's seen a bit of a resurgence.

In this video I thought I’d do a bit of a deep dive into the topic. So sit tight while I go over why some productions still choose to shoot on film over using digital cameras and outline the whole process of how film is shot, from pre-production and production all the way to it’s post production workflow.

WHY SHOOT ON FILM?

Before going over how film is shot I think it’s important to understand why it’s shot.

On the surface digital has many apparent advantages. It’s often cheaper. It’s possible to roll for much longer. There’s less room for exposure or development errors. You can view the rushes immediately. The list goes on.

When it comes to listing the pros for shooting on film it usually comes down to two factors: the look and the way of working. My favourite cinematographer, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, sums it simply: “It’s a better practical experience and aesthetic choice.”

Nowadays it is possible to recreate most of the colour and texture of film with digital footage in the colour grade, so that it’s perhaps a 95% match (or whatever number you want to use). However, I’m still yet to see the highlights and natural sharpness in a digital image effectively manipulated in a way that is 100% indistinguishable from film, particularly 16mm. And if you have the budget to shoot on film, and that’s the look that you are after, why shoot digitally then spend a load of effort in post trying to achieve a look and texture that is achieved out of the box with film.

Having spent time on both film and, of course, digital sets, I can attest that there is a marked difference in the vibe on these sets. Because you’re shooting on an expensive and limited commodity. When the film starts rolling through the camera everyone on set is far more focused.

Also the build up to shooting on film is more focused. Shots are carefully planned, movements and performances rehearsed and only a limited amount of takes are shot. This contrasts with the so-called ‘spray and pray’ method that sometimes happens when shooting digitally.

So for filmmakers that value both the aesthetic and more disciplined on set manner of working that film provides - shooting in 16mm or 35mm remains a viable choice.

PRE-PRODUCTION

Now that you’ve done the maths on the viability of the costs of motion picture film and chosen it as your working medium, how is it practically shot?

It all starts in pre-production.

Before arriving on set the director of photography will either conduct camera tests with various film stocks, or use their prior shooting experience to select a stock or a few stocks that are correct for the project. Today this means choosing between Kodak’s range - who are the only remaining manufacturer of motion picture film stock in the world. The cinematographer will base this decision on 3 factors, the ASA, or sensitivity of the stock, the colour balance, daylight or tungsten, and the look.

They’ll look at how the stock captures colour, each is subtly different, and the amount of grain and texture that they have. Stocks with a lower ASA, like 50D will have very fine grain, while higher ASA stocks, like 500T, will have more noticeable texture. Daylight stocks, rated around 5500K, have colour that is balanced to look normal in daylight. Tungsten stocks, around 3200K, have colour that is balanced to look normal under artificial tungsten light.

It is possible to shoot tungsten stocks in daylight and either add a warm 85 filter to correct the colour temperature, or shoot without a filter and correct the colour balance in the grade in post production.

Some cinematographers may choose multiple stocks, for example 250D for exteriors and 500T for interiors and night scenes, while others may choose to photograph an entire project with a single stock. It’s on them to estimate how many rolls of film stock will be needed, which the production team will then go about sourcing.

Short form projects like commercials will usually order all the film upfront, while longer feature projects will often keep ordering new film as they go. Often you can return excess film stock back to the supplier as long as it hasn’t been opened and loaded into a magazine. However it’s still best practice to acquire the amount of film as accurately as possible. You don’t want to order too much stock and lose money because it can’t be returned but you also never want to run out of stock or be unable to shoot. It’s the job of the camera team to determine how much stock needs to be ordered and pass that information on to production, who will order it.

PRODUCTION

With film stock in hand, or in the back of the camera truck, it’s now time to load it and start shooting. This is either done by a dedicated camera loader, especially when dealing with multiple cameras, or done by the 2nd assistant camera.

Since film captures an image by being exposed to light for a fraction of a second, it’s of the utmost importance that the raw stock is never exposed to any light. If a film can pops open for even a second outside the film will no longer be usable. That’s a good chunk of money down the drain.

The 2nd uses a light free film changing tent and loads the stock from the film can into the camera magazine completely in the dark. Once in the magazine and completely sealed the assistant then labels the magazine using tape.

Red tape for tungsten film or blue tape for daylight film. With a sharpie they’ll write down information like the roll number, what stock it is, the code that identifies the stock, how many feet of film is usable and any necessary developing instructions. The 2nd hands the mag to the focus puller who laces it onto the camera where it is ready to shoot.

Before rolling DPs metre how much light there is with a light metre and set their exposure.

Nowadays they often carry their own digital stills camera and double check their exposure with it. For example, if shooting 500 ASA film with a 180 degree shutter they set the digital camera ISO to 500, the shutter to 1/50 and manipulate their aperture until they find an exposure they are happy with.

The aperture of the film camera is then set and any necessary ND filters added or subtracted to cut down or increase the amount of light that enters the camera.

After each scene or shot is completed the assistant director will announce ‘check the gate’. The focus puller does this by taking off the lens and examining the film gate to ensure it is clean. Any dirt of hairs on the gate means the shot will be ruined. If the gate is clean the 1st AC announces ‘good gate’ and the production moves on to the next shot. It’s the job of the 2nd AC to consistently check the film counter to know when the magazine will run out.

Once all the film in a mag has been shot it is removed and carefully unloaded in the tent by the 2nd. They put it back in its can, seal it securely with tape and place the tape label from the magazine onto the can.

At the end of the day they will make a camera report, stating all the rolls that were shot with all the necessary information. From the 3 copies of the report 1 copy goes with the raw footage to the film lab to be processed, 1 goes to the production team for their records and 1 backup copy is kept by the 2nd.

POST-PRODUCTION

Once the film arrives at a lab, such as Cinelab in the UK or Fotokem in the US, the first thing that needs to happen is to develop it. The film is passed through a combination of chemicals. This sets the image on the film as a negative. Once developed, the film can now be handled in light without concern.

In order to edit the footage it needs to be converted to a digital format so that it can be worked with in the same way as files from a digital camera. To do this the film is either scanned or goes through a telecine.

For a telecine, as the film passes through a machine it is captured and recorded as a video file in real time - usually in HD. A scan is slower, more expensive and records much higher fidelity video files. The most common modern industry scanner is the Scanity HDR.

Each roll of film is put onto the spools of the scanner and motors run the film past a gate. At the gate each individual frame of film which was shot is scanned at either 2K or 4K resolution and saved as a digital DPX file. It is capable of scanning up to 15 individual frames every second.

These DPX files are uncompressed and lossless with very high dynamic range. This means they are similar to RAW files that are captured by some high end cinema cameras like ArriRaw or Redcode Raw and retain a huge amount of colour information.

Due to the high quality of the files they are fairly large. About 24 minutes of footage can be stored on 1 terabyte.

These files are then worked with in a digital post production workflow similar to how digital RAW files would be worked with. Once edited, those lossless files will be graded by a colourist, who will find the desired levels of saturation and contrast and correct any colour balances that are off.

Finally, the finished, graded footage along with the final sound mix will be converted into a DCP, a digital cinema package, basically a hard drive, which is used to digitally project the final film in cinemas.

Occasionally a film-out is done where the final DPX files are converted back to a film print, which is projected in cinemas the old school way - with light.

Why High Resolution Isn't Always A Good Thing

Let’s talk a bit about what resolution actually is and why I think high resolution isn’t always a good thing.

INTRODUCTION

What is it with this recent obsession with high resolution images? From gaming, to smartphone cameras, to what we talk about on this channel, films and cinematography. Why is the highest peak of photography associated with high resolution?

If you’ve ever worked professionally with cameras, the first thing that people like to ask is: does it shoot 4K?

Maybe part of this is based on our continuous pursuit of technological advancement. We tend to think that newer, bigger, sharper, faster, is always better. Well I think this isn’t always true. Particularly when it comes to art. So let’s talk a bit about what resolution actually is and why I think high resolution isn’t always a good thing.

WHAT IS RESOLUTION?

Some quick background on resolution. It refers to the amount of detail that an image holds. This can be measured in different ways but in the world of video and digital cinematography it is measured in pixels - tiny elements which record light.

Each pixel records a measurement of light and converts that data to a colour. I like to think of pixels like bricks in a building. With each brick painted in a different colour.

When you have a small wall made up of very few bricks, the image will appear more blocky or low resolution, whereas if you have a massive skyscraper with a ton of bricks, an image will appear clearer with greater detail.

If you set this YouTube video to 240 pixels it will be low res and blocky. If you set it to 1080 pixels it will be higher res with greater detail. Most digital cinema cameras use Bayer sensors to capture light in pixels with a red, green and blue pattern. 1000s of red, green and blue pixels are combined to create a representation of reality.

But enough with all the technical talk. Why does resolution matter? Surely the more detail that a camera can capture the better the image is?

Well, this is where I disagree. Just because an image can be recorded in 8K and resolve extreme detail it doesn’t mean that it is always appropriate to do so.

WHY HIGH RESOLUTION ISN’T ALWAYS A GOOD THING

In the world of art, painting photo-realistic images that are super sharp is one method of expression. You also get other painters that paint with broader, more abstract strokes that express feeling rather than only focusing on creating the highest fidelity image that perfectly represents reality.

Both are valid forms of expression.

In the same way, some filmmakers may prefer to tell their stories with less refined brushstrokes using a medium with a lower resolution that captures less detail like 1080p or even 16mm film as opposed to an 8K digital camera.

High or low resolution should be seen as a tool rather than something which is mandated. An image being captured in a higher resolution doesn’t make it inherently better. Resolving huge amounts of detail through high res capture means that things like skin will reveal every pore and blemish. Whereas resolving less detail gets rid of these unflattering flaws in a natural way.

It’s like when you meet someone in real life. Your eyes don’t fixate on the fine details of a person’s skin. They focus on the face as a whole. Photographing faces at a slightly lower resolution removes the focus on micro details. I think that the way in which cinema is viewed now also makes super high resolution images a little bit off-putting.

The way in which films are consumed by audiences is undeniably changing. We’ve gone from sitting way back in a cinema viewing projections on a large screen to watching content up close on laptops or phones. The larger the image projected and the further away you are from it, the more subtle the level of sharpness becomes. So when you watch Netflix on your laptop a few inches from your face the sharpness of the image will feel magnified.

I think the close viewing of high resolution video on high resolution screens results in images which are overly sharp images and a bit less…romantic. Perhaps this is just personal preference but, aesthetically, I find that super crisp digital cinematography can come off as feeling more video-y. More like broadcast TV on a 4K screen.

And actually, I don’t think I’m alone in this. Not amongst cinematographers anyway.

I’ve camera assisted on loads of shoots, and I’ve witnessed an overwhelming percentage of those DOPs pair high resolution digital cinema cameras with either diffusion filters, like an ⅛ or a ¼ Black Pro Mist or a Glimmer Glass, or pair them with vintage lenses. This is to take some of the sharpness and edge off of the high resolution digital sensor. Too much sharpness just feels artificial and unnatural.

Far fewer cinematographers pair high resolution digital cameras with modern high resolution lenses like Leica Summilux-Cs, the Alura or Master Primes without any filtration. And most of the time this is where the client or studio demands that the product must be very sharp.

I think this pursuit of maximum resolution and clarity follows the same pursuit of perfectly santitised, idealised images which are created for many contemporary mainstream Hollywood movies.

For example, myself and my filmmaker friend always joke about the fact that most featured extras in the background or actors with smaller roles in Hollywood films these days are now cast to super good looking, young models. Instead of the average, everyday folk which would be present in older movies. Like, come on, are these really what experienced scientists look like?

In the same way I think an overly sharp presentation of reality creates a cinematic world that is, photographically too perfect.

Finally, an important consideration when choosing gear is not only the creative or photographic look it has but also it’s economic and practical implications. This isn’t really a consideration for high budget films, but for lower budget projects, higher resolution cameras are more expensive to shoot with. More storage space on hard drives is required and more processing power is needed to edit and deal with that footage in post production.

CONCLUSION

Now I’m not saying that all films should be shot on 8mm film or at 720p. I think that for most digital projects, shooting and finishing them in a standard 1080p or 2K format is probably enough resolution to yield a sharp enough, but not overly sharp result.

However my main point is that sometimes 2K doesn’t feel right. Sometimes 8K is correct for capturing the project. Sometimes a 2K scan of 16mm film is correct. Some films should be finished in 4K.

Certain stories may benefit from capturing extreme details, giving images a hyper sharp, artificial digital look or benefit from the extra pixels needed for intensive visual effects work.The choice of the resolution should always be a practical and artistic choice that is motivated by the story and not just a default decision that is mandated or enforced.

Just because technology can do something, doesn’t mean it’s always right.

Cinematography Style: Maryse Alberti

In today’s episode I’ll give some background to Alberti’s career, go over her philosophy on cinematography and the gear that she has used in order to translate her vision to the screen.

INTRODUCTION

Maryse Alberti may not be as well known by mainstream audiences as some other cinematographers which I’ve featured in this series, but the strength of her career as a cinematographer speaks for itself.

She has a prolific track record in both documentary and fiction filmmaking, often choosing films that deal with real subject matter, true to life characters and situations that are interesting and elevated but grounded in reality.

In today’s episode I’ll give some background to Alberti’s career, go over her philosophy on cinematography and the gear that she has used in order to translate her vision to the screen.

BACKGROUND

“I grew up in the south of France. I didn’t have a TV, I didn’t see a TV until I was 12 years old…I just fell in love with movies when I came to the States because I stayed with people who had a TV in every room.”

After moving to the US in 1973, Alberti developed a career in capturing images, starting out by working as a still photographer in a field which isn't exactly the traditional roadmap to a career as a feature film DP.

“I ended up on the x-rated movie set where I was the still photographer…When I started to work on x-rated movies I started to meet people. The crews in New York were young people out of Columbia or NYU. It was kind of the training ground, one of the training grounds…Since I didn’t do film school that was kind of my film school.”

After starting out making film industry contacts in the ex-rated world she then got involved in shooting documentaries. Her break as a cinematographer came when she shot H2-Worker which won the Jury Prize for best documentary and best cinematographer at Sundance and launched her career as a DOP.

Throughout the years she has worked as cinematographer in both the documentary and the feature world, for many esteemed directors such as: Todd Haynes, Stephanie Black, Martin Scorsese, Ryan Coogler and Ron Howard.

PHILOSOPHY

Alberti’s career mix of documentary and fiction work has resulted in a style of working based on realism and cinema vérité.

Cinema vérité or observational filmmaking is a documentary style which attempts to capture reality in a truthful manner, by observing reality and trying to draw attention away from the presence of the camera. Although paradoxically, some argue that the very presence of a camera alters how reality is captured.

Either way, to blend into the background as much as possible, this style is often characterised by a minimal gear footprint. The very act of using less gear will impact the look of how a film is captured.

“From a cinematographers point of view you learn to work with very simple tools and very few people…Docs is another way of working. It’s more instinctual, it’s less intellectual.”

However, Alberti still recommends thinking about the subject of the documentary and basing the photography on the story.

Therefore, although I’d argue that a portion of her photography can be characterised by a vérité look, her style does of course change depending on the nature of the story.

A key difference between her work on documentaries and features comes from the level of intentionality. Long form work is more of an intellectual process with lots of prior reflection on creating a visual language, which is then executed by exercising and maintaining ultimate photographic control. Whereas in documentaries there is more scope to embrace improvisation and capture moments as they play out in real time.

For most documentary interviews Alberti will arrive at a location without seeing it beforehand, whereas when working on features she’ll usually have up to 8 weeks of prep time to scout locations and discuss production design with the director.

An example of how her taste for a natural, vérité look transfers over to her fiction work can be found in The Wrestler.

“I mean the whole film has a very naturalistic look. When I went to look at locations and went to look at a wrestling match I tried to make it work for the drama of the film. To keep it as real as possible. So that you felt you were in a real place.”

She did this by using natural looking lighting and motivated, handheld camera movement - skills which she had developed during her work in documentaries.

GEAR

“In general do I prefer film?...It depends on the story...Some stories are best told in the digital world. In documentary I think it’s a question of economics.”

When it comes to selecting gear for a project, she of course considers which equipment can achieve the desired look, but, perhaps equally as important, is the practical side of the gear selection.

When she started her career, shooting on film was the only viable option for attaining a decent quality image. A lot of her early documentary work was shot in 16mm due to it being a cheaper medium than 35mm which was needed to facilitate the lower budgets of documentary and higher shooting ratios. She mainly shot with Aaton cameras, such as the lightweight Aaton LTR 54. Even though 16mm was cheaper, it was still a costly process to photograph a documentary.

“When we did H-2 Worker…we went to Jamaica with 5 rolls of film because we didn’t have any money. You had to be very careful of the questions you asked and when you rolled.”

At approximately 11 minutes of run time per roll, this meant they had less than an hour of footage which they could shoot. Compared to today where a single interview may be longer than an hour.

Working on digital now allows filmmakers to be far more free about when they roll the camera and allows directors to have a conversation in interviews rather than asking very specific questions in an economic way. Alberti therefore prefers the practicality of digital over film when shooting documentary. It’s economic benefits, ability to roll for extended periods and smaller size outweigh the look of film.

She now uses cameras such as the Canon C300, the Sony Venice or variations of the Alexa for feature films, with different lenses like Hawk V-Lite anamorphics, Master Primes, Cooke S4s, or Angenieux zooms.

Although it is dependent on the story and subject matter of the project, much of her work has featured extensive handheld camera movement which is motivated by the movement of the characters. Perhaps this is due to directors wanting to work with her for her experience in producing quality handheld work in a vérité style.

She has operated the camera herself, but for larger feature films which require a more intensive focus on lighting, she has delegated the handheld work to camera operators. As a lot of the movement tracks the movement of the characters, it can make scenes feel a bit more ‘real’, like the actions of the actors are being observed rather than deliberately performed in multiple takes.

Alberti’s lighting does occasionally differ between projects depending on the type of story, but a lot of her lighting tries to be as naturalistic as possible, so naturalistic that the audience doesn’t even notice that the space is lit.

She does this by only supplementing the sources of light that are already present in the location. For example if sunlight is already coming through a window she may place a film light, like an HMI, outside that window to mimic the same direction and quality of the natural light. This is particularly necessary in fiction where consistent lighting conditions are required throughout a scene - which may be shot over the course of half a day.

Where possible she’ll place lights out of sight so that they can shoot a scene 360 degrees without being limited by lighting gear. She also uses textiles and diffusion gels to soften the quality of the natural or artificial light.

For interiors she’ll sometimes place practical lights in a location or use additional lights overhead like Mac 2000s to give the room a bright enough exposure to shoot in or to balance the brightness of different levels of illumination.

CONCLUSION

If I had to sum up her style, I’d say that Maryse Alberti is a cinematographer whose work in fiction is an extension of her documentary work.

Many of the characteristics of cinema vérité, such as a handheld camera and naturalistic lighting are carried over onto the feature films which she shoots but are executed on long form jobs in a more considered, deliberate and controlled manner than her more improvisational documentary camera work.

Her ability to capture a realistic feeling portrait of reality has contributed to her being an incredibly influential DP in both the world of fiction and documentary alike.

4 Camera Moves Every Filmmaker Needs To Know

Each choice made by cinematographers or directors should be a deliberate one that is responsible for visually communicating information or an emotional tone. In this video I’ll look at four common types of camera movement, go over how they are technically achieved, with what gear, and uncover how each can be used to communicate different emotional tones.

INTRODUCTION

The way in which the camera moves isn’t an arbitrary choice made by filmmakers, or, at least, it shouldn’t be. Each choice made by cinematographers or directors should be a deliberate one that is responsible for visually communicating information or an emotional tone.

From early on in cinema, people worked out that the camera presents a point of view and that moving the position of the camera in different ways during a shot can have different effects on how that shot is perceived by audiences. The way in which information on screen is presented, and in what order that information is presented, can also be controlled by the motion of the camera.

So today I thought I’ll look at four common types of camera movement, go over how they are technically achieved, with what gear, and uncover how each can be used to communicate different emotional tones.

PAN & TILT

Let’s start with the most basic and easiest to achieve camera movement - the pan and tilt.

Panning directs the angle of the camera on a horizontal axis. From right to left or from left to right. Tilting the camera moves it on a vertical axis, angling it upwards or downwards.

These movements are most often done on a tripod head, which can pan or tilt the camera in a smooth motion without shake. However, other types of gear can be used to pan to tilt, such as: a stabilised remote head like a Libra, by whipping a gimbal up or down or controlling its motion remotely, using the motion of a Steadicam, or even panning or tilting the camera handheld.

Both a pan and a tilt are usually used in combination to achieve what I’d call motivated camera movement. This is where the camera’s motion mimics that of the motion on screen.

For example, if a character moves around during a scene the operator may pan or tilt with them so that they remain the focus and do not leave the shot or ‘break frame’ as we say. By following the motion, the camera takes on a more subjective visual language that is more focused on a specific individual and their actions. As opposed to a wide locked off frame that doesn’t move and is more observational and objective.

The easiest way of quickly communicating which character in the story is most important in a scene is to follow their movement by panning or tilting with them.

Panning and tilting can also be used to reveal important information to the audience. For example the camera may start on a character and then tilt down onto an object. Tilting down to this object is a way of directing the audience’s eye to an important detail or piece of information in the story and saying ‘Look at this. Pay attention to it. It will be important later.’

The speed at which the camera tilts or pans will also create different tones.

A slow pan over a landscape may be used to build a sense of anticipation or gradually reveal the magnitude of the space. Whereas a quick whip pan makes a shot feel much more dynamic and is used to inject energy into a scene in a way that is more stylised.

PUSH IN & PULL OUT

A push-in physically moves the camera closer to its subject, usually at a gradual speed. The opposite is a pull-out where the camera steadily moves further away from its subject. So for push ins the shot size will go from wider to tighter and for pull outs the shot size will go from tighter to wider.

Although these moves can be done handheld, they are more commonly done with rigs that keep the motion smooth, such as a dolly, a slider, a Technocrane or a Steadicam.

The more slow and smooth the movement the more natural and subtle the emotional effect. The faster the motion the more abrupt, stylised and impactful it becomes.

For me, slowly pushing in on a character, especially during an important moment where we move into a character’s close up, makes me get inside that character's head. The camera is literally drawing you into their world. This movement makes you concentrate more on what the character is talking or thinking about. Often this move is used when characters are dealing with some kind of internal conflict or during a pivotal moment in the story.

The pull-out works in an almost inverse way. Instead of pushing in closer to the mind of the character, we pull away from them and become increasingly detached. This move can therefore be done to isolate a character on screen and introduce a sense of loneliness.

Another function this move has is to reveal a space or information. Starting in a close up and then pulling backwards will slowly reveal more of the location to the audience, better contextualising the character within their space.

Since the push in and pull out are not motivated by the movement of the character, it is more of a stylistic choice and is therefore in danger of losing its impact if it is overused or continuously done for every close up.

TRACK

A tracking shot kind of speaks for itself. It’s what I’d call a move where the camera physically moves through a space from a start to an end position - often tracking the movement of its subject.

Usually this is done with a dolly by laying a line of tracks and then pushing the dolly along those tracks on a straight axis, sometimes maintaining the same distance between a subject and the camera. Track positioning can also be more diagonal, where the camera tracks sideways but also gradually closer or further away from its subject.

This move can be done on a Steadicam, especially for sequences composed of longer takes with different axes of movement, or where the terrain changes gradient and placing tracks becomes cumbersome. Tracking shots done from directly behind or in front of a character are also commonly done with a Steadicam or without tracks on a dolly on a smooth, even floor.

Like with panning and tilting, this movement can be motivated, based on the movement of the characters.

For example, characters walking from right to left can be followed by tracking in the same direction. Again, this increases subjectivity, shows you what the main focus of the shot is and puts you in the literal footsteps of the characters.

Sometimes filmmakers use a counter track, where the dolly moves in the opposite direction to the subject. Usually this is done in a swift move to increase the energy and tempo of a shot. As the camera moves against the motion of the subject, it decreases the length of the take so is usually inserted as a quick cut within a sequence. For this reason, cars are often shot with counter moves from a Russian Arm, which increases the feeling of motion and speed.

Tracking through a space alongside a character in a longer take also gradually expands the scope of a location and introduces the audience to a space as we are exposed to new backgrounds as the camera moves.

BOOM

Booming refers to moving the camera up or down on a vertical axis.

Boom shots are usually associated with camera cranes which are used to lift or drop a camera using an arm. But for more limited moves they are also commonly done with a dolly, which has a smaller hydraulic arm. These two methods are popular for their stability and smoothness of movement and easy control. Some other gear used for boom shots may include a drone, a spidercam or rig using a pulley system, or a Towercam.

Booming up can be used to reveal more information using a single shot. For example, it could boom from an object, point A, up to a character, point B. This is a way of pointing out to the audience that the object at point A may be important or hold significance to the story. It creates a link between the two points.

Even in the case of the cliche example of characters driving off into the sunset on an open road, point A starts on the characters in a car which then booms up to point B, the open road. This move therefore creates a link between the characters and the open road, which may represent possibilities, freedom, or hope.

As with the push in, booming up and down is often not motivated by movement and should be used sparingly to avoid overuse and minimising its impact.

Also, in the same way as a tracking shot, booming can reveal more of a landscape or setting and is therefore often used to uncover the space as either an establishing shot at the beginning of the scene or as a closing shot at the end of a scene.

CONCLUSION

There we have it. Four types of basic moves which can be used to control how information in a movie is presented.

When interpreting and coming up with camera movement context matters. The same move made to capture different stories in different contexts, at a different pace, in a different manner with different gear may change the effect and meaning that move has on an audience.

So, when you’re planning your shots ask yourself these questions: What is the focus of the scene? What information do we need to present? In what order? Whose perspective is the story being told from? Should the movement be motivated? Or does the camera need to move at all?

These four moves are also just the tip of the iceberg. Some directors like combining some, or even all, of the above moves into a single shot if it serves the telling of the story. Because, really, how the camera in a film should move is only limited by budget, the three dimensions and our imagination.

What The Metaverse Means For The Future Of Cinema

In this video I’m going to do some speculating and take you through what the metaverse is and the potential impact I think it may have on the future of cinema and on visual communication.

INTRODUCTION

Visual communication as an industry has rapidly expanded over the past few decades. This is partly due to the internet providing more platforms for visual art to be viewed and interacted with, as well as increasing access to technology tearing down obstacles in the way of producing art.

Just over 10 years ago if you wanted to make a documentary it required using large and expensive, clunky broadcast cameras, highly expensive film stock, or low fidelity DV cameras. Once it was eventually made you then had to find a TV broadcaster willing to screen it, and if you were lucky enough to sell it, you’d need more luck just to break even on your costs of producing the documentary.

Now, people can pick up a consumer mirrorless camera, or even a phone, and get an amazing image right out of the box, then distribute the final film any number of ways online.

But what does this have to do with the metaverse?

Well, in a similar way that inexpensive digital cameras and the internet transformed the possibilities of documentary filmmaking, I think the metaverse could also have an enormous effect on how films and visual media are made, distributed and interacted with in the future.

In this video I’m going to do some speculating and take you through what the metaverse is and the potential impact I think it may have on the future of cinema and on visual communication.

WHAT IS THE METAVERSE?

On the 28th of October 2021, Facebook announced their intention to devote a huge amount of resources towards creating their version of the metaverse, signaling their intent by even renaming their holding company Meta.

Whether this bodes well or poorly for the future, one of the biggest companies in the world throwing all their chips into the metaverse pot is significant.

So what exactly is the metaverse?

“You’re going to be able to bring things from the physical world into the metaverse. Almost any type of media that can be represented digitally: photos, video, art, music, movies, music, books, games, you name it.” - Mark Zuckerberg

The metaverse is a space created on the internet which uses 3-D virtual environments. While it is still in its infancy, the metaverse involves integration between virtual and physical spaces. So people interacting in this environment will be able to create their own avatar or character that represents them, place that avatar in a virtual space, manipulate them with hardware like VR tools and effectively live a life in this space that includes consuming a variety of art forms and visual entertainment - including films.

The metaverse that Meta is currently developing will likely use a motion capture system, such as the Oculus (owned by...you guessed it...Meta), to allow players to explore the online space and interact with user generated content.

There’s definitely the possibility for filmmaking to exist and be incorporated into this future online world. But also, I think the core skill of filmmaking, which is visual communication, is already being used in developing the metaverse, whether through virtual reality, augmented reality or gaming.

WHAT THE METAVERSE MEANS FOR FILMMAKING?

So how will the metaverse change the way that movies are produced?

To understand this I think we need to know the four main categories that largely determine the cost of producing a film: sets, actors, crew and gear. The metaverse holds the potential to remove or change all of these boundaries.

Let’s start with sets. In the Metaverse, with a little bit of programming, you can create whatever location you want. In real life you may not be able to block off three avenues in New York to shoot your student film, but in the Metaverse any location you can imagine could become a reality.

Secondly, actors could be replaced with avatars representing any form. Or, actors could still be captured in real life and then placed within a 3-D virtual environment.

Third, crew. The only crew you’ll need are people to capture any live action footage and a team of programmers to do the post production digital grunt work. The hundreds of on set crew members needed for larger productions will be greatly reduced since, well...there won’t be sets.

And fourth, gear. Far more minimal camera and lighting gear will be needed to capture live action. Rather than lighting an entire space, now all that needs to be lit is a character and a green screen. Expensive gear that was once used for the bulk of capturing the footage will now be replaced by computers.

So it may seem that all of these prohibitive boundaries that there once were to make a movie will now dissolve and anyone will be able to produce a blockbuster from the comfort of their own home.

I think this yields interesting opportunities. Just as cheaper digital cameras, editing software and an increase in distribution platforms had an impact on how documentaries are made, I think this jump in metaverse technology has the potential to yield similar possibilities in visual communication.

However, I also can’t help but also be a bit sceptical.

While certain live action aspects of filmmaking, such as sets and actors, may move into the virtual space, it won’t exactly be cheap to make movies. I think celebrity actors will continue to be in demand for their ability to attract an audience and will continue to be paid premium rates whether their performance is in the real or virtual world.

I also think that many of the costs saved on crew, gear and locations will just be re-allocated to hiring a large team of programmers and designers to create the virtual movie - similar to how large budget games are produced.

In the end, when it comes to mass entertainment I still think the same players will dominate. The people who are going to be able to produce the highest-end films will still be the production companies with the largest budget, greatest resources and marketing power.

To remain on the cutting edge of technology, to employ the most talented filmmakers or artists and to promote the end product will always take a lot of money - whether in the real world or the metaverse.

While I think the metaverse and virtual reality filmmaking has many exciting possibilities and may change the landscape of independent filmmaking through creative user generated content, I think that the space of mass entertainment will continue to be dominated by the production companies that are able to spend the most money.

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

So why does it matter to those who are working, studying or interested in film and what impact will it have on them?

Although what I’m suggesting is hypothetical, we can already find practical examples of film production companies working in this virtual space. Visual effects companies such as Digital Domain, founded by James Cameron, are increasingly producing more and more work, such as characters, in the VR and AR space.

While the transition for those who occupy roles in the visual effects and post production side of the film industry is relatively straightforward, what does it mean for other crew members who are used to applying their trade in a two dimensional world - like a cinematographer for instance.

As we transition into this new virtual space there will be a period where capturing the real world will be incorporated with visual effects work. This is actually a job that cinematographers are already performing. Almost every film that is produced nowadays includes some degree of visual effects work incorporated with live action cinematography. Combining traditional photographic skills for capturing images, along with more conceptual skills is already a necessity for most DPs.

For example, Bradford Young was tasked with combining these skills when shooting Arrival.

“It was on us to determine the tenor of the visual effects. The visual effects aren’t going to determine how we make the film. We make the film and the visual effects come into play later.” - Bradford Young, Cinematographer

On Arrival the creative team decided on a set of rules when filming the live action, such as keeping the focus on the character in the foreground.

“We never threw focus or rarely threw focus to effects or a CG element. You know, we always kept it in the foreground. If we had four or five added helicopters we wouldn’t throw focus there and say ‘Hey, this is real!’...The film is not about that. The film is about what is happening in front of us.” - Bradford Young, Cinematographer

To me it would be sad to see sit-down cinema as we know it disappear in the metaverse (never mind the potential negative social effects the metaverse might have on the population at large). But one thing we can never escape from is that art is always changing.

Cinematographers of the future will be faced with tools for creating in the virtual world that may have been impossible before in the physical 2-D realm.

For example, even now with visual effects it is possible for cinematographers to shape light in a way that would have been otherwise impractical without digital help.

“We get out in these situations where we have a long walk and talk. Because of the environment that we’re in and because of the tools we have...people don’t walk with a 12x12 negative fill the whole walk. But when we do visual effects, we forget that it’s a visual effect, you’re lighting it so you can do whatever you want.” - Bradford Young, Cinematographer

The norms of how traditional creative systems are to be adapted are still being formulated, so being at the forefront of them as a creator is an exciting prospect.

CONCLUSION

I guess I’d sum up this piece by concluding that although the metaverse is still in its infancy, I think it’s indisputable that eventually filmmaking, and many other forms of entertainment, will continue to move into an increasingly virtual, online space.

As things become more and more virtual, filmmakers will need to adapt their skills from being more practical to being more conceptual. This process may be slow and take many many decades, but I have a feeling it may happen faster than we think.

The metaverse may open up interesting new possibilities for expression, but I think that the mainstream entertainment space will still be dominated by mass media companies that can spend the most. Bearing in mind that these are all predictions I think that there are a couple of things which most creatives should do to stay abreast of this changing visual world:

One. Stay informed and up to date on technological advancements.

Two. Continue honing and building your conceptual eye for visual communication and storytelling.

Because while the demand for your ability to physically photograph stories may dissolve over time, what has always been important, throughout the evolution of art from its earliest form up to what we have now, is the perspective of the artist. Having a strong artistic perspective and experienced eye for storytelling will ensure you’ll always have a job in whatever medium film, or visual storytelling, ends up being.

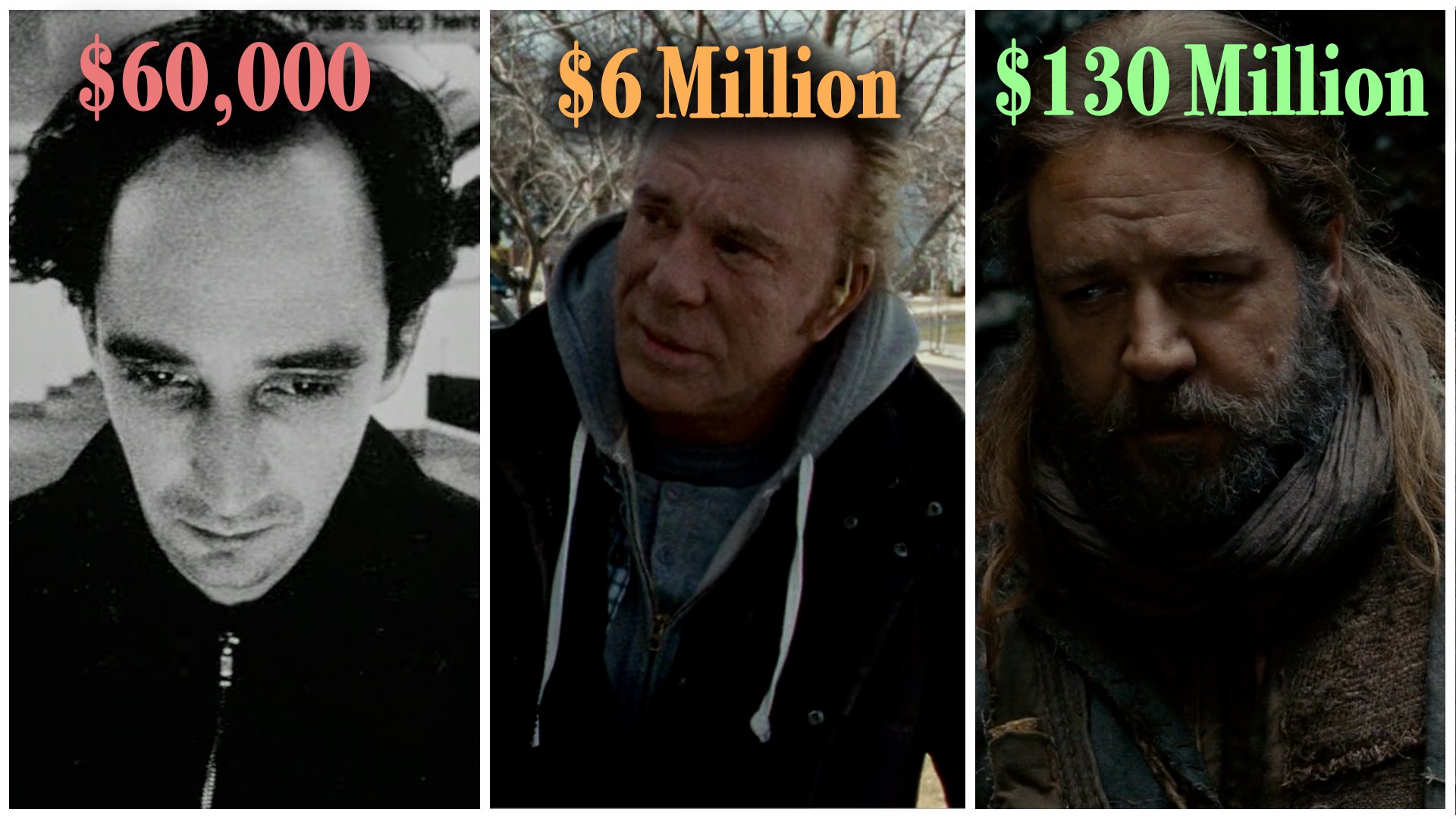

How Darren Aronofsky Shoots A Film At 3 Budget Levels

As I do in this series of videos, I’ll take a look at 3 different films made by Darren Aronofsky at 3 increasing budget levels: the low budget Pi, the medium budget The Wrestler, and the high budget Noah, to identify commonalities in his filmmaking and how his style has progressed throughout his career.

INTRODUCTION

The films that Darren Aronofsky makes occupy an interesting space. They straddle the line between experimental and realist, between mainstream and independent, between classical biblical allegories and contemporary tales.

However, what most of his films have in common is a strong emphasis on character and use of perspective to make the audience feel like you’re taking a journey in the shoes of those characters, not just observing their story from afar as an outsider.

As I do in this series of videos, I’ll take a look at 3 different films made by Darren Aronofsky at 3 increasing budget levels: the low budget Pi, the medium budget The Wrestler, and the high budget Noah, to identify commonalities in his filmmaking and how his style has progressed throughout his career.

PI - $60,000

Aronofsky’s introduction to filmmaking came from him studying social anthropology and filmmaking in 1991 at Harvard. His thesis short film for the programme, Supermarket Sweep, starred his friend and actor Sean Gullette. It was well received and won him a spot as a finalist at the 1991 Student Academy Awards. He went on to get his masters in directing from the AFI Conservatory, where he met and began working with his classmate in the cinematography programme Matthew Libatique.

When it came to writing Pi, like with many other low budget films, he decided to focus on a single character. This idea of doing a portrait character study was born out of the verite documentaries he would make in film school which focused on the story of one person.

The experimental, psychological horror film was set in only a few locations, with the primary one being inside a small apartment.

The movie was financed through an early version of what I guess you could call crowdfunding. Aronofsky and his producer Eric Waston went around asking every friend, relative and acquaintance to give them $100 to fund their movie. Eventually they were able to raise $60,000 which, along with a host of other favours, was used to make the film.

Some of those favours included getting the crew to work for deferred pay by granting them shares in the film which would pay out once the film was sold, paying the actors $75 a day and getting a free warehouse which they could use to build their studio set.

Around $24,000 of the budget went towards the cost of buying and developing 16mm film stock and much of the remaining funds were reserved for post production. This left very little money for gear rental, production design or locations on the 28 day shoot.

However, Libatique who would photograph the film, was granted enough to rent a Aaton XTR 16mm camera, three lenses and a free, although small, tungsten lighting package to work with. He chose the XTR for it’s lightness, which helped with the ample handheld work, along with its ability to shoot single frames, which they used for the stop motion board game scene. He got 2 16mm Canon zooms, a 8-64mm and an 11.5-138mm, and one Angénieux 5.9mm wide prime lens.

To support a surrealistic look that Libatique termed ‘low-fi stylisation’ Aronofsky decided to shoot Pi in black and white.

“Darren wanted to shoot Pi in black-and-white for both aesthetic and budgetary reasons. He wanted the most contrasty black-and-white possible, with really white whites and really black blacks.” - Matthew Libatique, Cinematographer

To achieve this look Libatique decided on using reversal film, Eastman Tri-X 200 and Plus-X 50 for daylight scenes, which have high contrast but less dynamic range than negative film. The latitude, the difference between the lightest and darkest part of the image, was so small that he only had about 3 stops before the highlights started blowing.

Which is difficult to comprehend when comparing to modern digital cameras like the Alexa, which can handle more than 14 stops of dynamic range.

Libatique’s lighting and metering of exposure had to be extremely precise as being even half a stop too bright might mean losing all detail. On top of that he used a yellow filter to further increase the contrast and get rich blacks.

Their philosophy behind the look of the film was to create a subjective perspective that put the audience in the shoes of the protagonist. They did this by shooting with a single camera, shooting over the protagonist’s shoulder and moving it in a motivated way. So when the character moved, the camera followed.

To increase this personal perspective they also used a macro lens at times to capture close details in an abstract way that also represented the character’s gaze.

A final example of this subjective perspective can be found in the stylised use of mounting a camera directly onto the actor’s body. Kind of like vlogging, before the concept of vlogging existed. This gave a personal, up close, subjective perspective that mimicked the increasingly manic movement of the character.

They rigged a still photography tripod to a weight belt that was attached to the actor and mounted Aronofsky's own 16mm Bolex camera with a 10mm lens to the tripod. He altered the frame rates, overcranking his close up, and undercranking the camera at 12fps for his POV shots to show his increasing dissociation with the real world.

Aronofsky spent the majority of the low budget on sound in post production, where he was able to find additional funding, as he knew that without a strong sound design and mix the film would fall flat. He was able to get a score from Clint Mansell who, like the crew, worked for a deferred fee.

He was therefore able to pull off Pi on an incredibly low budget by: writing a story with limited locations, characters and no large set pieces, getting crew to work for deferred pay, pulling lots of favours, and using a small gear package to create a vividly experimental, subjective, surrealist look.

THE WRESTLER - $6 Million

After winning the Directing Award at Sundance Film Festival for Pi and selling it to distributor Artisan Entertainment for more than a million dollars, Aronofsky kick started his feature film career.

Following the bigger box office budget flop of The Fountain, Aronofsky picked a lower budget script for his following film, a realistic dramatic portrayal of an aging wrestler, written by Robert D. Siegel. He raised a budget of $6 million to make the movie.

After Nicolas Cage initially expressed interest in the role, it was eventually granted to Mickey Rourke.

Although Rourke admired Aronofsky’s work and wanted to make a film with him, he wasn’t overly happy about the script as he felt that some of the dialogue didn’t accurately portray how his character would realistically talk. Therefore he, along with Aronofsky, re-worked much of the dialogue in the script until they were happy.

Due to the free way that Rourke liked to work, apparently around 40% of the final film was improvised and initially unscripted.

“I tried to approach the film as free as possible. I didn’t go onto set as I usually do with very specific notes and shot lists. I tried to be open every morning to what Mickey was going to bring and then try and figure out after I saw that the best way of capturing it.” - Darren Aronofsky

For example, most of the wrestling scenes were scheduled during real wrestling matches. The crew would wait till about halfway through a match and then bring Rourke into the ring and shoot a bit, using the real energy from the crowd who turned up.

As it was very physically demanding Rourke would then leave the ring, re-gather his energy and come back to shoot a bit more. During these breaks the real wrestlers would keep the crowd entertained while Rourke recovered and the cameras were reloaded with new film stock.

To capture this free way of working, Aronofsky devised a style and approach which both supported how he wanted to tell the story and which was practical.

There’s not much realism in the world of wrestling, which is all about over the top performance, however the life of the main character in The Wrestler is too painfully real. So Aronofsky decided to create a film grounded in cinema verite, which followed his protagonist, literally, with an up close and intimate handheld camera. Again taking on a more subjective perspective, however this time one that was far more centered around realism.

To create this look he hired cinematographer Maryse Alberti who had a track record in both fiction and documentary work.

They shot it on Super 16mm, which suited both the modest budget, as it is cheaper to shoot than 35mm, but the grain from 16mm was also reminiscent of the verite, documentary look that they were going for.

To create the look for this realistic portrait, Alberti shot almost entirely with natural light, mainly using whatever practical lighting was already in the locations. She would sometimes bring in a couple of lights or tweak them slightly in order to achieve exposure but otherwise left the lighting alone whenever possible.

The only exception was the final match, which was a built set. In this she mimicked the lighting setups of many of the other matches which they had already shot - based around using overhead lights and lighting the four corners of the ring.

Since most of the movie was assembled from long shot sequences, photographed from the shoulder on a handheld camera, she chose the Arri 416 for her camera operator Peter Nolan.

She paired the camera with a set of Zeiss Ultra 16 prime lenses and two Angenieux Optimo zooms, a 15-40mm Lightweight and a 28-76mm.

Due to the length of the takes, Peter Nolan came up with some interesting techniques for operating the camera. One involved strapping an applebox to his waist so that when sat down with the camera during a take he could rest his elbows on the apple box and hold the camera steady.

Sometimes these long takes required plenty of choreography and involved grips holding up flags at various points to block out lights from casting shadows of the camera.

So Aronofsky in some ways maintained his perspective of shooting the film in a subjective way, yet moved away from experimentation and more into realism.

The Wrestler’s higher budget allowed Aronofsky to hire a cast of well known actors for this performance heavy drama and pay all the cast and crew fair rates, yet they saved money by shooting on 16mm, in a rough, verite, documentary style which allowed them to work on real locations, without any large production design, grip or electrical setups.

NOAH - $160 Million

The Wrestler proved to be both a critical and financial success.

A few years later he turned to producing a huge scope story which he had been interested in since he was a child: the biblical story of Noah. True to his style, Aronofsky adapted Noah to the screen by straying from the brief source material and including a more surrealistic, allegorical story, which visualised and presented themes through exaggerated characters and images.

Producing such a large scope script, with its epic set pieces, required a hefty estimated budget of around $160 million. Aronofsky turned to his regular DP Matthew Libatique to shoot the film.

“We were handheld on Noah, but it wasn’t like we were floating from character to character in a vérité style. I think we’ve matured as filmmakers and can focus on what’s important, which is subjectivity and storytelling.” - Matthew Libatique, Cinematographer

But, like on The Wrestler, Aronofsky wanted to be able to move the camera in a way that was very fluid and natural, but also in a way that was very controlled. Therefore Libatique mainly used Arricam LT cameras, which were light for handheld work yet also tough enough to handle working outdoors in the elements for extended periods without breaking.

With them he selected Zeiss Ultra Primes, mainly sticking to 3 focal lengths, a wide 24mm, a medium 50mm and a long 85mm.

This time he shot on 35mm, a format with greater clarity and less grain, more suitable for an epic. Libatique shot in the higher resolution 4-perf format for any shots that required post production special effects, and in 3-perf for regular scenes.

Although most of the film was shot handheld with a single camera from a more subjective perspective, certain scenes, such as the large flood scene, was shot with four cameras, two on Chapman Hydrascope cranes and two on the ground, to more quickly cover the many shots needed in this expensive set piece.

The magical exteriors were mainly filmed on location in Iceland.

When it came to lighting characters in those exteriors not much was done except for trying to block scenes so that the actors could be backlit by the sun. Libatique likes to keep things as naturalistic as possible so avoids lighting exteriors whenever he can, only using a muslin bounce occasionally when he needed more fill.

As Libatique says: “Fighting nature to mimic nature is a large undertaking.”

However some interiors and night scenes involved enormous setups. For example, to cover the battle scene at night his team hung 18 daylight balanced helium balloons from condors. Then, two 100-ton cranes each carried 100-foot rain bars, and another 100-ton crane carried an 80-foot rain bar, with two 32K balloons on each rain bar.

Another huge setup was the Arc set, which was constructed in three levels in a studio in New York. Lighting such a big space came at a cost.

For day scenes the rigging grip built a giant white ceiling bounce, made up of smaller UltraBounce surfaces. Bouncing into it were 20 20Ks, which they rigged on each side, underslung on the truss, and also 25 Mole-Richardson 12-lights.

Once production was wrapped, 14 months of post-production work began. During this time Aronofsky tasked Industrial Light & Magic with extensive VFX work including creating 99% of the animals in the film, dropping in background plates, like mountains or trees, and of course creating the mythical elements such as The Watchers.

As with all of Aronofsky’s films dating back to Pi, a score was composed by Clint Mansell.

Noah was therefore produced on a blockbuster budget, which was needed to create massive production design builds, enormous grip and lighting setups, a cast of stars and enormous set pieces which required over a year of innovative visual effects work.

CONCLUSION

Darren Aronofsky’s filmography covers an interesting range all the way from low budget independently financed films up to large studio blockbusters.

Despite this large growth in scale, his preferences for visualising themes and presenting them through characters using a subjective perspective has carried over throughout.

While the maturity of his filmmaking might have grown, it maintains elements of original experimentation and an eye for the surreal that he’s had since his earliest foray into cinema.

The 3 Basics Of Cinematography

I think the most important duties of a director of photography or DP can best be distilled into 3 basic elements: exposure, lighting and camera positioning and movement. Let's take a look at these 3 aspects of cinematography to show why they are crucial in order to fulfil the DPs overarching function of building and capturing the look of a film.

INTRODUCTION

As you can probably gather from the name of this channel, I usually make videos that skip over some of the basics and make content that is a bit more, well, in depth. But since I’ve had some requests in the comments to make a video that goes over the basics of cinematography I thought I’d do just that.

As the role that the cinematographer takes on is a fairly technical and complex one, it’s a bit tricky to distill all the nuanced things that they do into a single YouTube video. However, I think the most important duties of a director of photography or DP can best be distilled into 3 basic elements: exposure, lighting and camera positioning and movement.

These three elements align with the three departments on a film set which the DP manages: the camera, lighting and grip departments. To be a cinematographer you need to be able to control all three of these elements and manipulate them in order to capture a visual style which suits the story being told.

So let's focus on each one of these departments, or aspects of cinematography, to show why they are crucial in order to fulfill the DPs overarching function of building and capturing the look of a film.

CAMERA

Let’s start with a fairly necessary feature of cinematography, the camera.

To capture an image light passes through a glass lens and hits the film plane, which could house a digital sensor or a film stock. How the footage will look is determined by the amount of light that hits the focal plane and the sensitivity of how easily the digital sensor or the film stock absorbs that light.

This is what we call exposure. It refers to the amount of light that is exposed to the film plane. Letting in more light will result in a brighter exposure, while letting in less light will mean a darker exposure. One of the most important parts of a cinematographer's job is measuring and ensuring the correct exposure is achieved. Exposure is an important tool that DPs can easily use to create an image that reflects the correct tone and story.

A simple example can be found in comedies versus horror films. Typically comedies have a brightly exposed image which reflects the light, comedic tone of the story. While horror films often have a darker exposure which sets a broodier, scarier psychological tone.

To control exposure with the camera, the cinematographer can adjust three different variables: the shutter, the aperture and the ISO or film speed.

Motion picture cameras usually use a rotary disk shutter. This is a semi-circular disk that spins in front of the film gate. When the disk passes the film gate light will be blocked and not let in. As it turns there will be an open section where light will be able to hit the film plane.