Cinematography Style: Jeff Cronenweth

INTRODUCTION

In this series I’ve mentioned a recent trend of some younger cinematographers being drawn towards what I’d call ‘dark photography’ - where the actors are underexposed, backlit or illuminated in a low-key style.

Although there have been other early pioneers of this dark style of lighting, such as Gordon Willis - who I made a video on - Jeff Cronenweth is a DP who, to a large extent, is responsible for popularising this style, through his work on movies such as Fight Club or The Social Network.

His photography regularly features a dark exposure, a subtly desaturated image, a use of soft toplight, naturalistic imagery and smooth cinematic camera moves.

In this edition I’ll look at Jeff Cronenweth’s philosophy on photography and show some of the gear which he uses to execute that vision.

BACKGROUND

Jeff Cronenweth’s background in filmmaking is basically the holy grail.

His father was legendary American cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, known for photographing a number of classic films including his famous work on Blade Runner. His father introduced him to sets where he worked as a 2nd Assistant Camera during high school. After graduating he enrolled to study cinematography at USC and, post graduation, resumed working with his father, this time as a 1st AC.

During this time he worked for famous cameramen such as John Toll and Sven Nykvist, from whom he picked up lots of lessons and precious experience. In working with his father he was introduced to David Fincher, who Jordan Cronenweth shot for. During this time his father would let him do some of the on-set grunt work of lighting, placing the camera and operating.

Cronenweth was hired as B-Camera operator on Seven and served in a similar capacity on The Game. When it came to selecting a DP for Fincher’s next project Fight Club, Cronenweth got the call.

This accelerated his career as a feature film cinematographer.

He has shot feature films, commercials and music videos for directors such as: David Fincher, Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Romanek.

PHILOSOPHY

“You may not have a style. I hate it when people try to brand you and put you in a box because I think each opportunity creates its own opportunities to find something new. Even if it resembles something you’ve done before it’s still going to be something different.”

Like all cinematographers, Cronenweth’s style is flexible and changes depending on the suitability of the story.

The story should inspire the visual style. The visual style shouldn’t just be placed haphazardly on top of every story.

Although he hates to be boxed in, I’ll now try and do exactly that and connect some common threads that Cronenweth carries across various projects. Much of Cronenweth’s work uses naturalism or realism which he’ll then enhance for cinematic effect.

In Fight Club Fincher and Cronenweth created a visual contrast between Edward Norton’s nine-to-five life, which was lit and presented in a natural, reality-driven way, and Brad Pitt’s character, for which they wanted a more deconstructed, torn-down, hyper-real look.

This visual metaphor supported the change in the story from real and mundane to hyper-reality. It was done by gradually making the lighting moodier and darker, making the costumes and make-up more unconventional, and making the sets progressively dirtier and more extreme.

Another example of Cronenweth’s preference for naturalism can be seen in his use of practical lights, lights that you can see in a shot. He uses these practicals to motivate his placement of supplemental film lights, mimicking the direction, quality or colour of the on screen practicals. Likewise, he has also used the natural light that the weather offers up and supplemented it to feed the story.

“I think the weather depends particularly on the story you are trying to tell. In Girl With the Dragon Tattoo it needed to be cold and it was cold...and it was so imperative that that element, to some degree, was a character of the movie. In the setting it was imperative that you felt what these characters were going through physically in order to appreciate their journeys.”

Cronenweth uses his photography, particularly in his work with Fincher, to convey a more visceral feeling to the audience. The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo feels cold. Fight Club feels dirty. The Widowmaker feels claustrophobic.

He is able to do the job of a great cinematographer - convey a feeling using images.

GEAR

When preparing for a long form project Cronenweth does ample preparation by doing camera tests, going through various lenses, film stocks, lights or production design palettes, in order to set the look of the movie.

To prepare for Fight Club he tested different film stocks by pulling, pushing and flashing the negative. Flashing is where the photochemical film stock was quickly exposed to a tiny amount of uniform light prior to developing the film. Typically it was done at a film lab. This allowed darker areas of the image to show more detail, rather than reading as pure black.

Before digital cameras, he used film stocks from Kodak, such as their 250D, 500T and 100T emulsions.

When shooting on film he regularly used the Panavision Platinum, but also occasionally used Arri cameras such as the 435.

As digital cinema cameras became available on the market he made the change over to using them instead.

“I miss, like all of us, the texture and the quality of a projected film image and even to some degree that shutter which was comforting. But when you spend so much time perfecting an image and you walk in a multi complex and you walk from one screen room to the next screen room and it's completely different, I almost let go of it a little bit in order to get some of that control back.”

A large part of his preference for digital photography and digital projection stems from the consistency which they provide. When screening a 35mm print it may get scratched, be dirty, or the projector may be dim.

However when a digital projector screens a bunch of 1s and 0s from a DCP it should be more or less identical to the final image which the cinematographer saw in the grading suite.

Although he has shot on Arri cameras - I know because he shot on the Alexa Mini LF when I worked as a 2nd AC for him - he shoots much of his digital work with Red. He was an early adopter of the Red One MX back on The Social Network in 2010. All subsequent projects which he shot for Fincher he also used Red cameras such as the Epic MX and the Epic Dragon.

Another reason for using digital, especially when working with someone like Fincher who does lots of post production work and likes every shot to be stable, is due to its resolution capabilities.

On Gone Girl he recorded the entire sensor at 6k but framed for 4K by placing the image that he wanted inside the central frame lines. Therefore there was extra information on the outsides of the digital negative. This allowed the image to be stabilised in post production software, which used some of the extra information recorded, without needing to crop into the framed shot.

Cronenweth regularly shoots on spherical lenses, another preference that he picked up from working with Fincher. If he needs to frame for a 2.40:1 anamorphic aspect ratio he usually prefers to extract the ratio from Super35 than use anamorphic glass.

This is because spherical lenses come in a more flexible range, which include more focal lengths. They let in more light and can therefore be used in conditions with lower light - such as reading practical lights on a street at night. He uses various focal lengths and often opts for lenses with a good degree of sharpness such as Panavision Primos, Master Primes, or Leica Summilux-Cs.

Cronenweth achieves his so-called ‘dark look’ by regularly placing his lights overhead or behind characters, rather than directly from the front. Placing lights overhead, which is called top light, is a great way of creating a spread of ambient light to a scene. Since many interior locations do come with overhead lights, placing a light overhead is also a choice motivated by his desire to supplement reality.

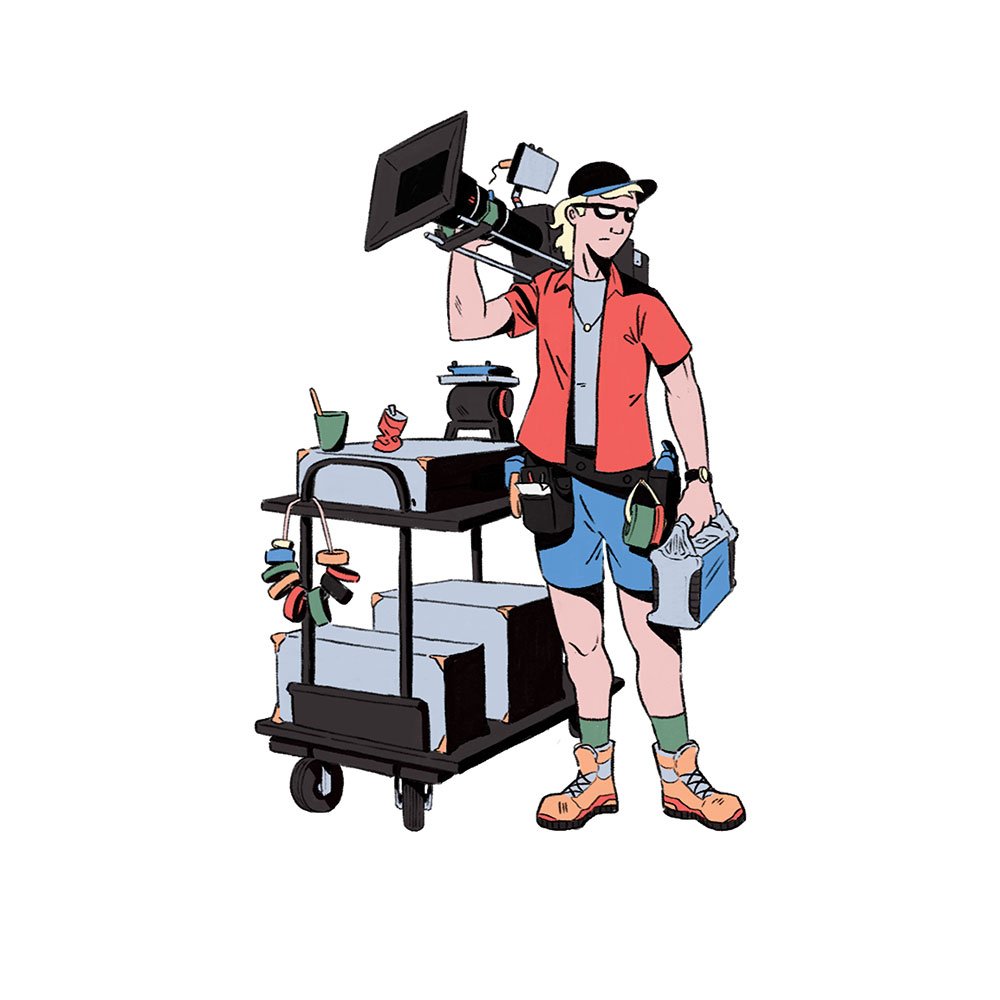

He often uses lights like Kino Flos for this, rigged by his grip team.

Shadows cast from this light will fall straight down and you’ll often get a nice, soft, low level, return light bounced back up from natural surfaces such as tables. To separate characters from dark backgrounds he’ll then use a backlight or a rim light. This is a light placed behind the character which creates an outline of light that distinguishes them from a darker background. To save some detail in the shadows he may then fill in the scene with a low level light such as Kino Flo with diffusion from a 216 gel or muslin textile in front of the light. As a final touch to bring out a ping of light and presence in the eyes he may rig a low power light like an Obie or a small LED under the mattebox.

When it comes to moving the camera he tends to prefer using more traditional gear which creates classic cinematic movement, such as a dolly, a technocrane or occasionally a Steadicam.

If the budget allows, he’ll also opt for a helicopter with a stabilised head like a Shotover, over using a drone, for more dynamic and traditionally cinematic aerial shots.

CONCLUSION

Although he admittedly doesn’t like to be boxed into a particular style, if I had to box him in a bit I’d say that Cronenweth’s photography relies on more traditional Hollywood conventions, such as stable camera movement, while pushing the envelope with bold, dark lighting.

His camerawork of course isn’t a cinematic monolith and does adapt and contour to the correct shape of the story that is being told.

In so doing he uses a technical eye and experience to summon a feeling amongst viewers using nothing but 2D images.