Understanding Focal Length In Cinematography

When you watch a movie you’re looking through a lens that has a specific viewpoint, a specific way of interpreting depth, scale, and distance. And that viewpoint, expressed as a focal length, affects everything.

INTRODUCTION

When you watch a movie, you’re not just looking through a camera, you’re looking through a lens that has a specific viewpoint, a specific way of interpreting depth, scale, and distance. And that viewpoint, expressed as a focal length, affects everything.

Today, we’re going to explore what focal length actually is, how it works, how different formats can change the field of view, how focal lengths shape emotion, and most importantly how filmmakers can use lenses as creative tools.

WHAT IS FOCAL LENGTH?

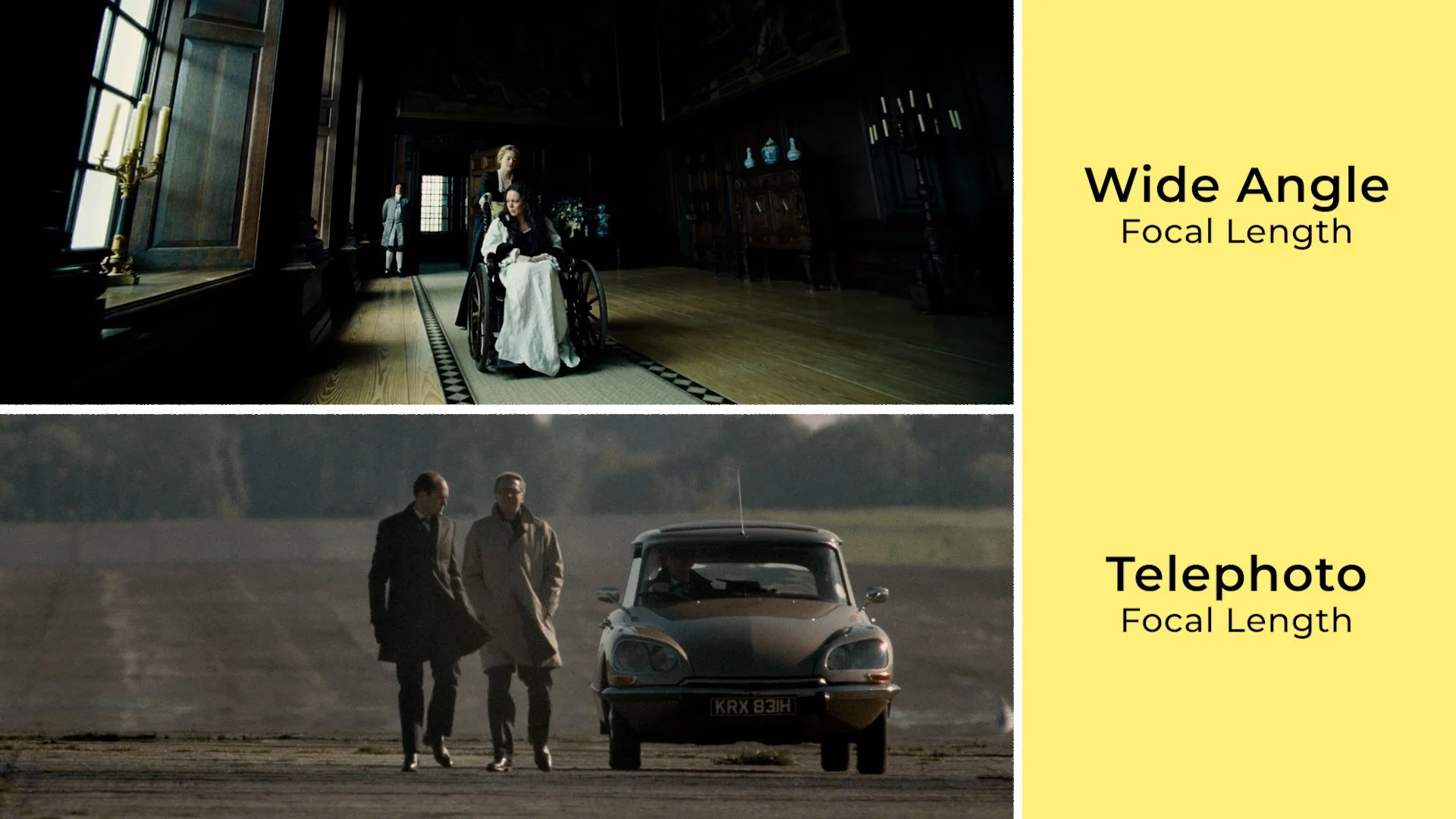

At its core, focal length is a measurement for each lens, usually written in millimetres, that affects how wide the image feels, how compressed or expanded the space is, and how connected, or distant, the audience feels from the characters.

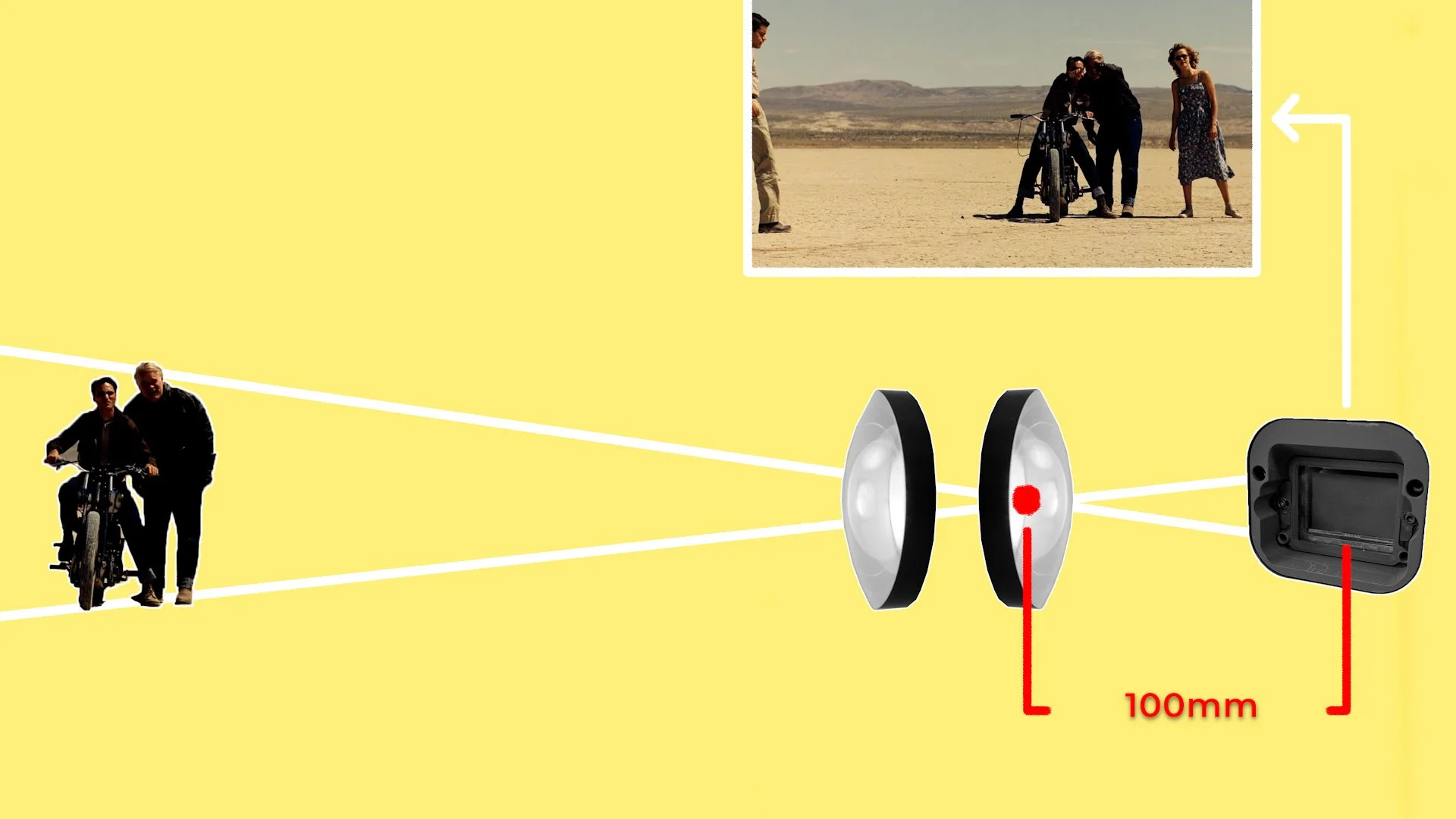

Inside every lens are glass elements that bend and converge light. When these elements bring incoming light rays to a point of focus, that point has a physical distance from the sensor.

Focal length is therefore calculated as the distance between the optical centre of a lens and the camera’s sensor or film plane when the image is in focus on objects far away at infinity.

A shorter focal length, such as 16mm, bends light more strongly, producing a wider field of view. While a longer focal length, like a 100mm, bends light less, producing a narrower field of view.

This physical behaviour becomes the foundation for the visual language of wide angle, normal, and telephoto lenses.

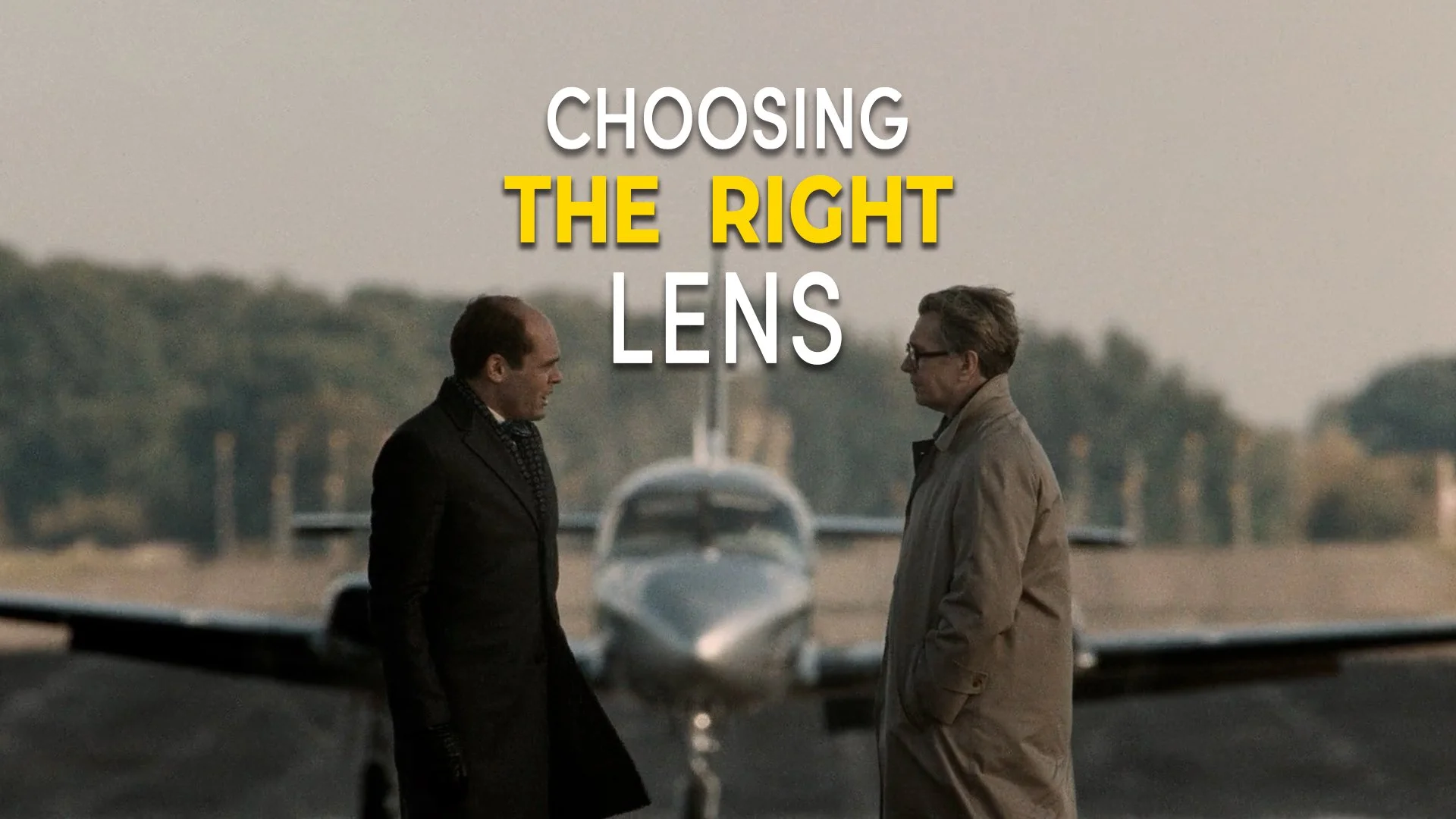

WIDE ANGLE LENSES

Wide angle lenses, all the way from a 6mm fish eye, to 18mm, 24mm, or 25mm focal lengths, capture more of the environment with a wide field of view. They stretch space, exaggerate distance, and make movement across the frame feel more dynamic and easier to track by a camera operator.

When the camera is placed physically closer to the subject, such as when getting a close up, wide lenses create a sense of immediacy. Faces feel more intimate, the world feels larger, and motion feels alive.

However, because of how these wide lenses bend light, it may also start to distort spaces or people’s faces in an unnatural, exaggerated way, especially as the lens gets closer to the subject.

MEDIUM LENSES

Lenses around 35mm to 50mm sit in a sweet spot that feels natural and what we call a medium, normal or standard focal length. They don’t distort space too much like wide angle lenses do, nor do they compress it too heavily like telephoto glass does.

A 35mm gives a slightly wider, more energetic perspective, while a 50mm often feels clean, honest, and somewhere around what we associate with the natural field of view of how our eyes see the world.

Filmmakers often use these focal lengths when they want the audience to feel like an observer rather than a participant, on wide angle lenses, or a voyeur, on telephoto lenses.

TELEPHOTO LENSES

Telephoto lenses, such as 75mm, 100mm, 135mm all the way to 200mm zooms and beyond, compress space and offer a much tighter field of view. This means that to get a similar width to the frame of a wide angle or medium lens, you’ll need to move the camera much further away from the subject.

Not only does this make the footage feel more voyeuristic, but it also establishes a more voyeuristic relationship between the person on screen and the camera operator.

This spatial relationship may not always be desirable, such as when filming a sit down interview, where you may want the person asking the questions to be closer to the subject and able to empathise and interact with them more personally and casually, rather than shouting from across the other side of the room behind a telephoto lens.

Objects captured by telephoto lenses appear closer together. So backgrounds can be made to seem much nearer to characters than they are in reality. This can be used for moments of action or to make dangerous objects or animals appear like they are right next to the actor.

Backgrounds blur into soft washes of colour, and characters feel isolated from their surroundings.

These lenses flatten depth, slow down the feeling of movement, and often create a sense of tension or emotional distance.

Focal lengths come with another practical effect. The longer the lens is, the shallower depth of field it will have. Therefore, wide angle lenses will have a less blurry background, and be much easier and more forgiving to pull focus on and keep the subject sharp. Telephoto lenses will have a much softer, more out of focus background, and are much trickier for 1st ACs to accurately keep moving subjects sharply in focus.

CREATIVE USES OF FOCAL LENGTHS

Focal length isn’t only about technical behaviour. It’s a creative choice that can be used by filmmakers to subtly support and add to the visual storytelling.

Emmanuel Lubezki is famous for his extreme use of wide-angle lenses. Often for directors like Alfonso Cuarón, Terrence Malick and Alejandro González Iñárritu. In films like The Revenant, Children Of Men, and The Tree Of Life, he often uses 12mm, 14mm, or 18mm lenses which yield an incredibly wide field of view which often leads to faces distorting when framed for close ups.

Because of this extra width, camera bumps and shakes will be less prominent and noticeable - which makes these wider lenses better for smoother, less shaky handheld footage.

By seeing more of the background, the world becomes a character. You sense the cold, the terrain, the vastness, or the cityscape. The camera can move intimately close to actors while still preserving context - partly because of the expanded view and partly because wider lenses have a deeper depth of field where the background will be less blurry and soft and still distinguishable. Wide lenses dissolve the barrier between the audience and the scene, creating an almost first-person feeling.

The purpose isn’t just to go wide. It’s to bring the viewer into the environment and make the footage feel more immersive and subjective.

This technique is certainly not bound to one cinematographer, and has been used early on by directors like Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, or later, by Wong Kar-Wai, to visually exaggerate and distort faces, spaces, motion and emotion.

Moving a little tighter to more medium focal lengths like a 35mm or a 50mm - we have filmmakers who prefer to photograph in more of an objective and natural style.

Yasujirō Ozu famously preferred the 50mm lens and would use it almost exclusively in most of his movies. To him, it was the closest approximation of how humans perceive the world: simple, respectful, and honest.

He didn’t want to impose perspective onto the audience. Instead, he wanted the camera to observe, quietly and truthfully, as life unfolded.

A 35mm has been used to create a similar naturalistic window into the world in films like Call Me By Your Name, or a similar 40mm lens on Son Of Saul.

On the furthest end, the Safdie Brothers have mainly used long telephoto lenses for a completely different emotional effect: from 75mm to 360mm anamorphics or even a ridiculously long Canon 50-1000mm zoom.

In films like Good Time, Heaven Knows What, or Uncut Gems telephoto glass creates a compressed, chaotic, almost claustrophobic world.

Characters feel boxed in. Backgrounds crowd them from all sides and are blurred so that the characters are the sole focus.

This tension becomes part of the storytelling, and feeds into the traits of the characters and fast paced trajectory of the plots. Every shot feels like it’s vibrating with nervous energy.

Michael Mann is another director who consistently uses telephoto lenses, especially in urban environments in action thrillers like Heat or Collateral. Often favouring a 75mm or longer.

These lenses compress and isolate characters and create a visually tense, voyeuristic filmmaking language which creates a feeling of surveillance, alienation, and existential pressure. Making his characters appear trapped inside dense urban grids, like they are always being watched and moving through hostile spaces.

FORMATS & FOCAL LENGTHS

A final note is that the same focal length can yield a different wider, or tighter field of view when they are used on cameras with different format sensors or film gauges.

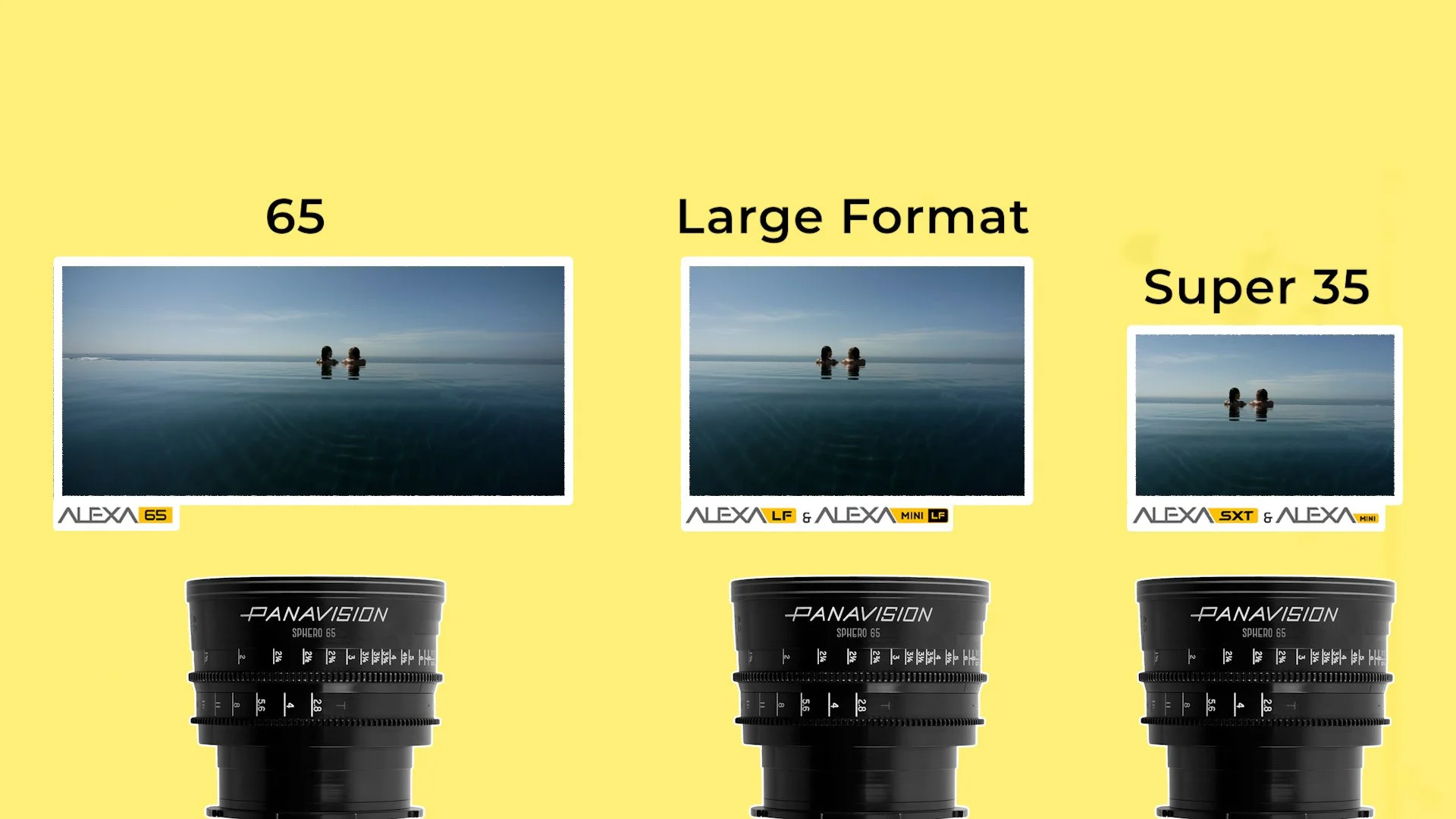

Super 35, whether on film or with cameras like the Alexa Mini or 35, is the traditional cinema standard. This format is usually what cinematographers have in mind when they think about the field of view of a focal length.

In comparison, 16mm film or similar sized sensors have a relatively small image area. Lenses therefore appear longer and images more cropped in. This gives 16mm its signature tight, intimate, energetic feel.

Full frame digital and large-format film captures a much bigger image area. Lenses therefore appear wider on these sensors. This format gives footage a sweeping, spacious feel with a very shallow depth of field, and portraits that have a sense of scale.

The focal lengths of the lenses themselves don’t change when they are put on different cameras, however smaller or larger sensors will just reveal more or less of the lenses field of view.

So, a 35mm focal length on a Super 35 camera will have approximately the same field of view as a 25mm lens on a 16mm camera, which should also be similar to a 50mm lens on a full frame sensor.

CONCLUSION

Filmmakers choose focal lengths not just to capture images, but to create unspoken meaning, to shape perspective, to draw the viewer in or push them away, to make characters feel vulnerable or powerful, connected or isolated.

The more deeply you understand focal length, the more you realise that every shot carries an emotional weight determined not just by what you point the camera at but by how you choose to see it.

What Is VistaVision?

Despite its vintage roots, VistaVision has quietly re-entered the modern filmmaking landscape through an influx of new movies shot on this 35mm film format. What is it, why did it disappear, and why is it suddenly popular again?

INTRODUCTION

Many, many decades before full frame cameras became all the rage, VistaVision emerged as the original, old school, magical, large format option. Influencing everything from camera design to the way modern cinematographers think about resolution and texture.

But despite its vintage roots, VistaVision has quietly re-entered the modern filmmaking landscape through an influx of new movies shot on this 35mm film format.

So in this video, we’re going to look at what VistaVision actually is, why it disappeared, and why it’s suddenly everywhere again.

HISTORY OF VISTA VISION

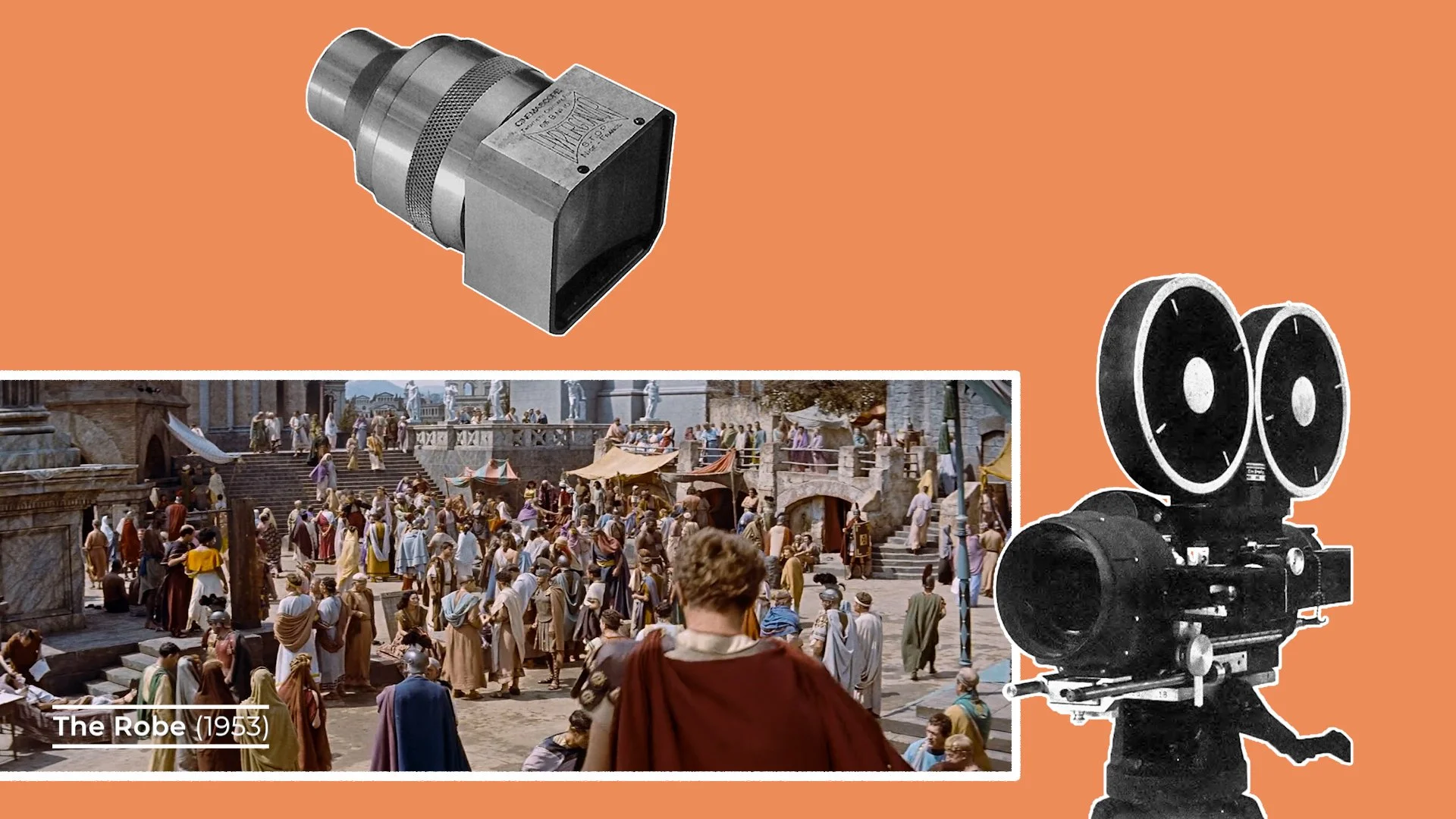

VistaVision was introduced by Paramount in the 1950s as a premium theatrical exhibition format.

At the time, Hollywood was in a technological arms race with movie studios experimenting with wider, sharper, more immersive 35mm images - on formats like Cinemascope which used anamorphic lenses to get a wider aspect ratio.

They hoped these new formats would pull audiences back into cinemas, after attendance massively declined with the invention of home viewing on TVs.

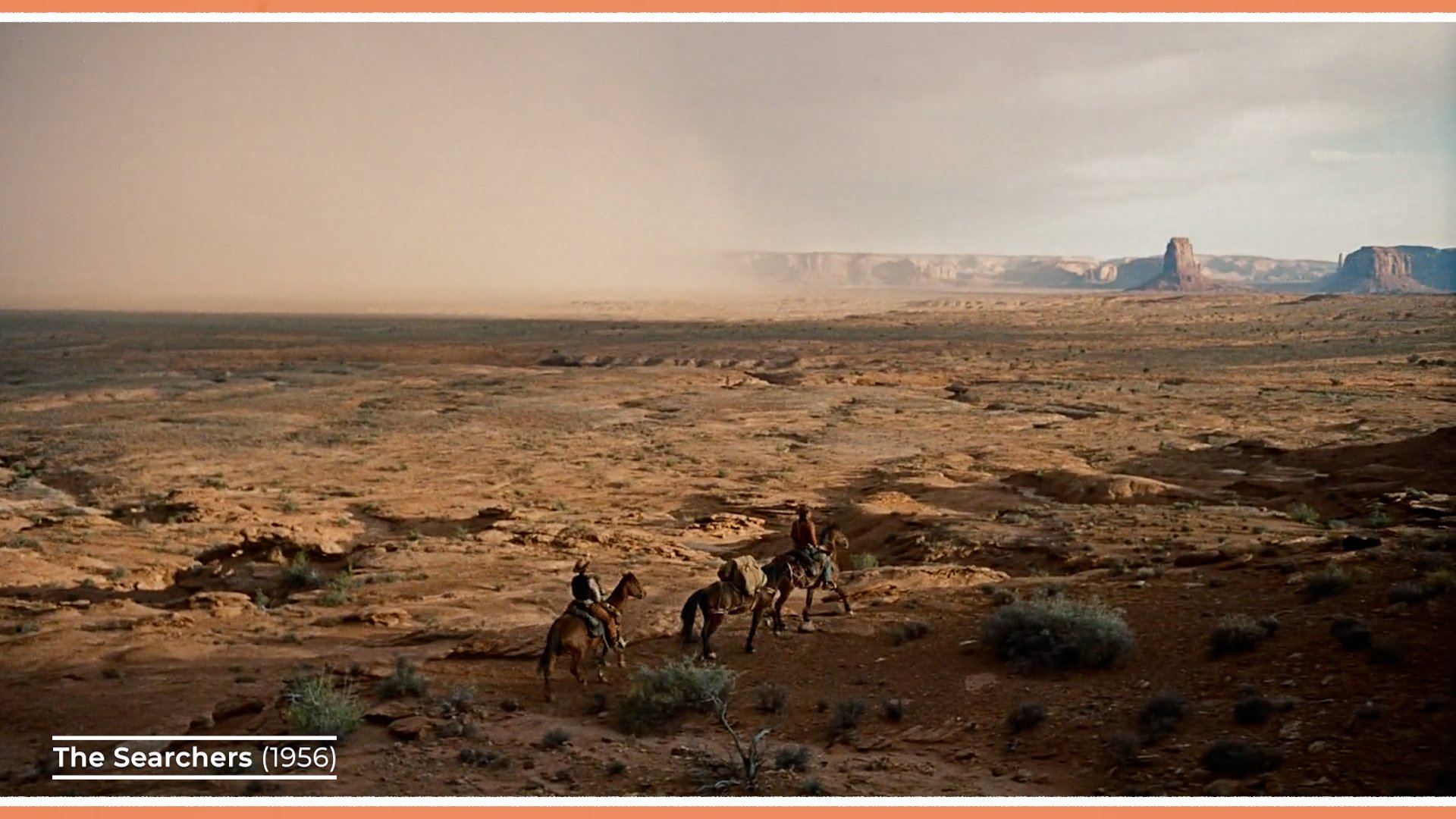

For a while, VistaVision delivered that larger than life, enticing visual experience with higher resolution, wider field of view images. Films such as Vertigo, The Ten Commandments, North By Northwest and The Searchers made full use of the format’s clarity.

But as the ’60s and ’70s arrived, VistaVision’s popularity declined. New widescreen formats, cost pressures, and the success of anamorphic 35mm meant that VistaVision workflows became too expensive and too cumbersome for most productions. And so, the format faded away.

However, I think cinema technology is kind of like fashion in that preferences for different technical gear often goes through cycles. And, much in the same way that TV in the 50s challenged cinema’s dominance, I’d argue that so too has the recent rise of streaming services forced studios and filmmakers to seek out larger than life exhibition formats and viewing experiences like Imax, or VistaVision to try to draw audiences back to the cinemas.

From 2024, VistaVision saw a small but meaningful resurgence. Films like The Brutalist, One Battle After Another, and Bugonia embraced it as a deliberate creative choice that provides those tactile qualities and large-format characteristics that are unique to VistaVision.

WHAT IS VISTA VISION

But why is VistaVision different and how does it technically work?

In order to understand this larger film format we first need to know how regular 35mm film capture works.

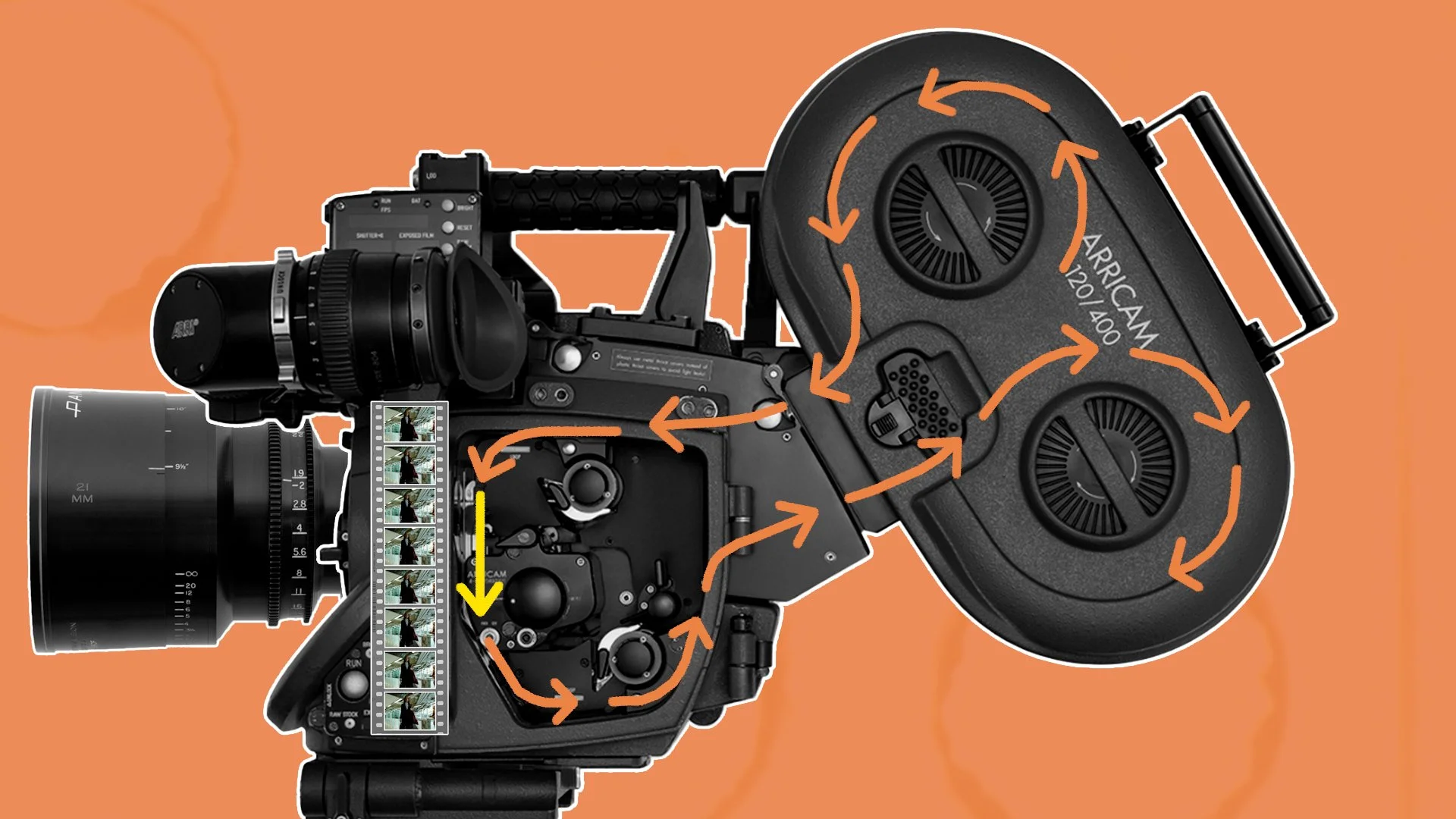

Normal 35mm cameras store film stock in what’s called a magazine. When the camera rolls, the unexposed film exits the mag, and passes vertically through a film gate where each frame is captured, before the exposed film is then stored once again in the magazine. The regular Super 35 format captures each image in a frame that is 4 sprockets or perfs tall.

VistaVision uses the same 35mm film, but captures each frame in a different way.

Instead of running the film vertically through the gate, it moves across the film plane horizontally. By feeding the film sideways, VistaVision is able to capture frames that are eight perforations long, which is roughly double the size of a standard Super 35 frame.

This is why VistaVision cameras look so distinctive. The film magazines are rotated 90 degrees compared to a typical 35mm camera, so that the magazine sits horizontally, feeding the film laterally across the gate.

That’s the essence of VistaVision: the same 35mm film - just used in a different orientation to maximize the negative size.

VISUAL CHARACTERISTICS

The appeal of VistaVision isn’t just technical: it’s mainly due to the visual traits it comes with.

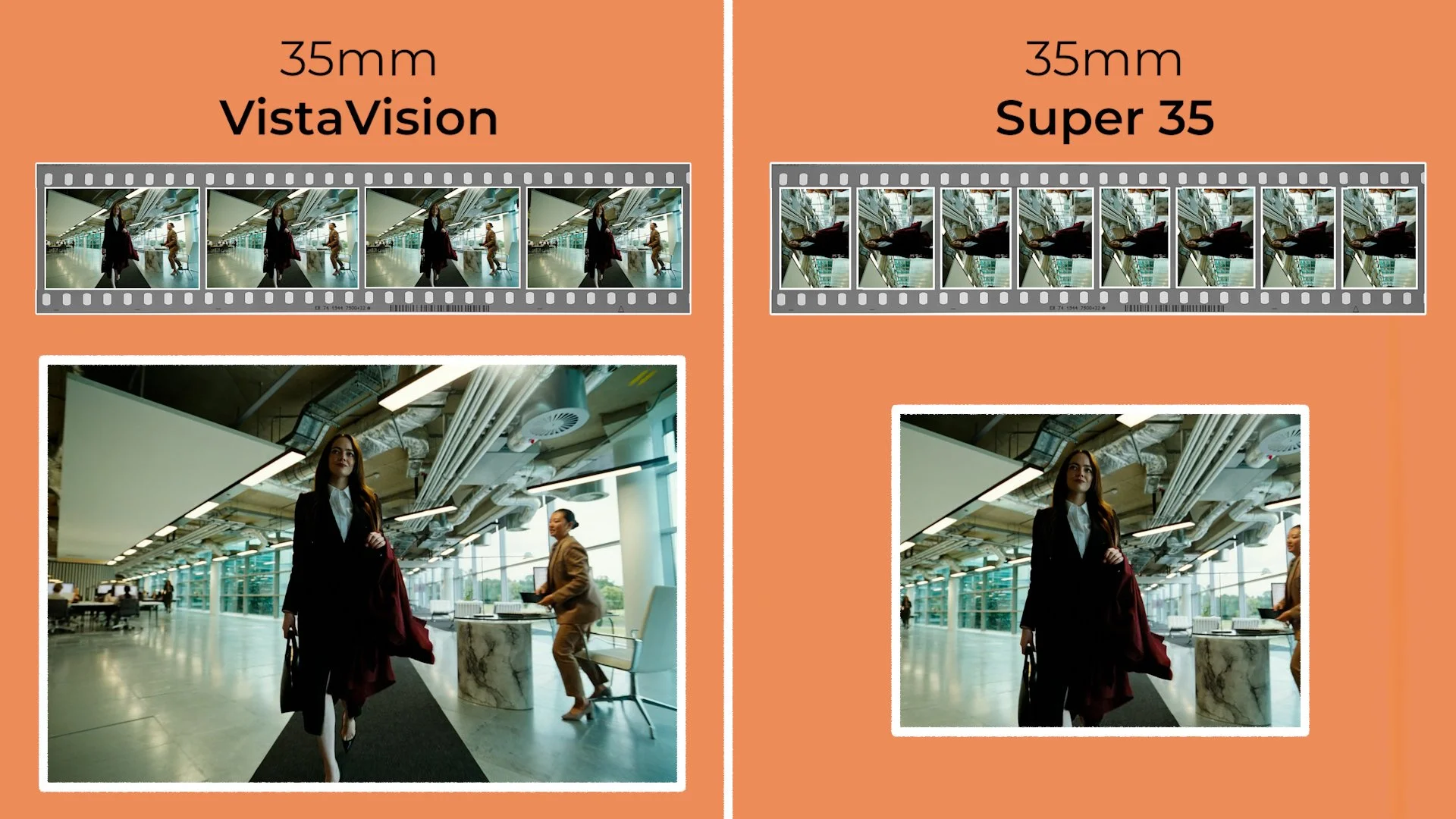

Because the negative size is physically larger than Super 35, more information is captured over a bigger area. This means that VistaVision offers exceptionally good clarity, detail and a highly resolved image.

Because of this high resolution, which helps with special effects, it was used as a specialist camera to shoot miniatures, such as on Star Wars, many decades before high resolution digital cameras were a thing.

When this high fidelity film image is scanned or projected the grain structure will appear tighter and less apparent due to the increased image area. Even high-speed stocks filmed in low light situations will have a slightly cleaner texture than Super35.

A secondary effect of this larger negative is that it yields a naturally wider field of view at equivalent focal lengths. For example, if you shoot a frame on a 50mm lens with a VistaVision camera and with a Super35 camera and place them next to each other, the Super35 frame will be about 1.5x narrower than the larger format image.

Practically this means that you can shoot on slightly longer focal length lenses and still maintain an expansive perspective, while getting the added benefit of a shallower depth of field, even in wide shots. Which many find to be quite a cinematic look.

Or, if you put a wide angle lens on a VistaVision camera, then it’ll expand the space even more. That’s part of why this format feels so immersive and dimensional.

Like a 35mm stills camera, the native VistaVision frame is closer to 1.5:1 or 3:2. Which is a slightly squarer frame with more height. Historically it was often cropped or optically printed to widescreen ratios like 1.85:1. Although occasionally some movies, like the recent Bugonia, decided to stick to the original 1.5:1 ratio of the negative.

Modern productions shooting VistaVision which will be finished with a digital post production workflow can choose almost any delivery aspect ratio while retaining the format’s inherent resolution advantages.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

For all its beauty, VistaVision comes with trade-offs.

VistaVision cameras are big - much larger than standard 35mm motion picture camera bodies. Their horizontal magazines add bulk, and the film transport mechanism requires space.

There are a couple different types of these old VistaVision cameras - like the Wilcam W-11. This camera is especially large and heavy, which means they are basically only designed to be used on a camera platform like a dolly or on a tripod.

One reason for the W-11’s bulk is that it's blimped. This means that when the motors run the film through the camera it is quiet enough to still record sync sound dialogue.

There is another slightly smaller and lighter VistaVision camera made by Beaumont. Although it’s a bit smaller than the Wilcam it’s still pretty enormous by modern digital cinema camera standards.

It is technically possible to shoot handheld or mount these Beaumont cameras to other grip rigs like a stabilised head or a car rig, yet their large size still makes it pretty impractical and challenging to do so.

A trade off for this smaller form factor is that these cameras are excessively loud, which makes it difficult if not impossible to record usable sound for dialogue scenes - especially indoors.

Another practical downside, which cinematographer Robbie Ryan spoke about, is these old cameras tend to get jams from time to time where the 1,000 feet of 35mm film flying through the camera gets stuck. If this happens it means the take will have to be aborted and started again.

The larger frame means standard Super 35mm lenses will not cover the VistaVision image area without vignetting. Cinematographers have far fewer lens options to choose as they are forced to select from glass which has sufficient coverage, often pulling from specialized large-format or vintage glass sets.

On top of tracking down the lenses, the rarity of these VistaVision cameras themselves can make them very tricky to source. Their age also means most of these cameras don’t have modern features like a good video tap - which means directors and DPs may not be able to view a clear image of what they will shoot on a monitor.

Because the VistaVision negative is twice as large, you burn through 35mm film stock at double the rate. Every take costs more and every reload is more frequent and the length of the takes you can shoot with one magazine is shorter. The budget implications can therefore be a serious consideration.

CONCLUSION

VistaVision sits at a fascinating intersection of old and new - born from mid-century innovation, abandoned for decades, and now rediscovered by modern filmmakers searching for a specific kind of cinematic texture.

It’s a reminder that film technology isn’t a straight line of progress but a series of cycles, with each generation finding new meaning in old tools. And as long as filmmakers continue exploring the expressive potential of the format, VistaVision will remain a powerful - if niche - option for creating images that feel both timeless and unmistakably tactile.

Cinematography Style: Dan Laustsen

In this video, we’re going to break down the visual language cinematographer Dan Laustsen often returns to - in his work with bold, imaginative directors like Guillermo del Toro and Chad Stahelski - and explore the technical film gear that he uses to do so.

INTRODUCTION

Dan Laustsen’s cinematography feels less like a collection of images and more like an atmosphere you step into. His work blends precision with a kind of dreamlike intensity, using bold, expressive colour palettes: rich greens, steel blue, deep ambers, and vivid contrasts that carve shape and emotion into every frame.

Paired with his preference for wider focal length lenses, which pull the viewer deeper into the environment, his images gain a sweeping, immersive quality. In this video, we’re going to break down the visual language Laustsen returns to and explore the technical film gear that he uses to do so.

BACKGROUND

Dan Laustsen’s path into filmmaking began in the 70s when he trained at the National Film School of Denmark and quickly found his footing shooting early projects with directors like Søren Kragh-Jacobsen. These films helped shape his instinct for strong visual storytelling through images that were expressive, stylised, and driven by atmosphere rather than strict realism.

As his career expanded beyond Denmark, he became known for collaborating with international directors who embraced bold, imaginative worlds, most notably Guillermo del Toro and Chad Stahelski.

Across these partnerships, Laustsen often gravitated toward elevated genre filmmaking - like action, fantasy, sci-fi or horror - where heightened visuals were expected. It’s in these spaces that his signature style thrives: rich colour, dramatic contrast, and a painterly sensibility that transforms fantastical stories into something operatic.

VISUAL STYLE

Perhaps the element in his work which most strongly stands out, is his expressive use of colour palettes. Nowhere is this more obvious than in his collaborations with Guillermo del Toro.

“Guillermo and me, we agree about the way that we like to make movies. We like the strong colours. We really love, as everyone can see, we love steel blue. We love that colour so much and we think it’s so good with the contrast with the amber and the red.”

This preference isn’t arbitrary, it’s grounded in one of the most fundamental principles of colour theory: complementary colours. On the colour wheel, blue and orange sit directly opposite each other, meaning they create the strongest natural contrast when placed together in the same frame.

This contrast isn’t just visually striking; it helps guide the viewer’s eye, define depth, and create an emotional tone that feels both heightened, fantastical and harmonious.

Laustsen uses this steel blue and amber palette often in his work, through a very deliberate approach to lighting. He often washes the majority of the environment in a cool steel-blue ambience, establishing a moody base layer that shapes the world and its atmosphere.

Then, cutting through that coolness, he introduces warm accents, such as pockets of amber or red from practicals like candles, lanterns, or lamps. These warmer sources illuminate key details, separate subjects from their surroundings, and bring a sense of visual rhythm - so that the colour in the frame doesn’t feel too monochromatic.

The push-and-pull between the dominant blue-green and the strategically placed warm highlights creates a pleasing colour separation, making the image feel both dimensional and emotionally charged.

Although Laustsen sees himself as a technician who is there to support the vision of the director, there are often some stylistic similarities to the films he shoots which extend beyond the lighting palette.

For many films that he works on, the camera takes on an almost third person, omniscient perspective, which represents the filmmaker guiding the audience’s eye around the space.

He does this by using a wider field of view which sees more of the set, rather than shooting everything in tight close ups with a shallow depth of field. This wider frame then often glides around the set, floating through the space, or following subjects like a wandering, observing, all knowing eye.

“I think that is the goal or the key. To shoot it wide and beautiful. As wide as we can.”

Whether capturing fluid, moving action sequences like in the John Wick films, or slowly tracking the walk of characters in the various Del Toro movies, he likes the camera to have lots of width and to be dynamic.

GEAR

When it comes to gear, Laustsen consistently chooses tools that support his expressive, stylised approach to cinematography. His lighting setups rarely aim for strict naturalism; instead, they embrace a heightened, almost theatrical quality.

A signature example of this is his use of strong, warm, single-source lighting. While these lights might be motivated by elements of real life, like a window catching late-day sun, their intensity, hardness, and direction often go far beyond what real sunlight would produce.

He frequently relies on large tungsten units like T24 or T12 fresnel spotlights or multi-bank fixtures like Dino lights. These have a warm colour balance, which becomes even warmer when he places ¼ CTS gels in front of them, and can be used to punch hard, sculptural beams into a room, or even to add or shape light outside into a strong beam such as simulating the sun rising.

The light will usually follow a single source approach, lighting actors from only one side and not using a counter fill light on the other side, so that the contrast remains high and the shadows are crisp and black.

He usually avoids placing film lights inside interiors, preferring to light through windows and with practicals, as it frees up the actors and the camera to move anywhere within the space that they’d like without needing to avoid capturing gear in the shot.

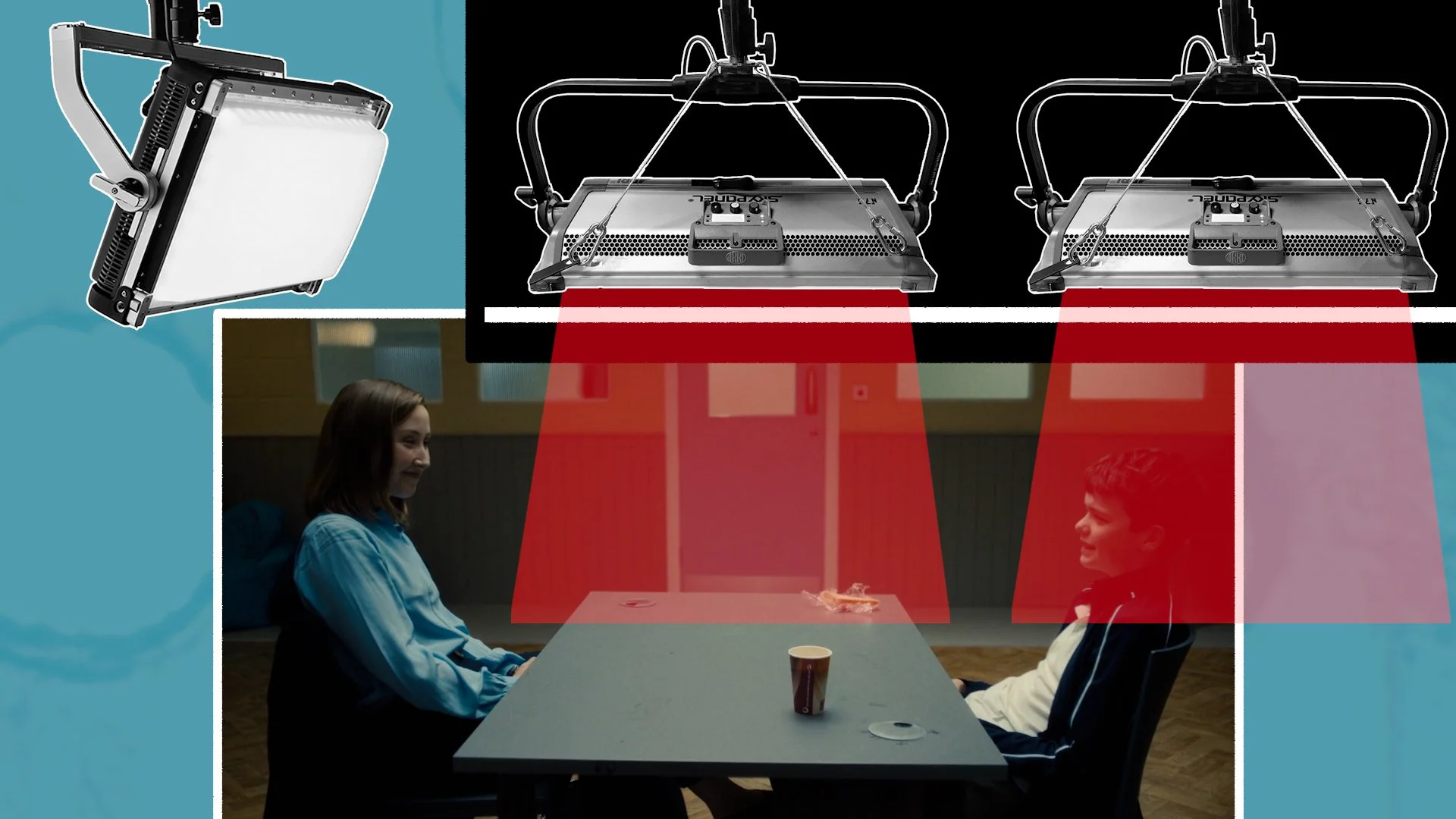

To create the warm, cool palettes in interiors or for night scenes that we mentioned before he’ll usually use LED sources, like Creamsource Vortex8s or Skypanel S60 or S360s, as they are easier to control and dim.

These lights will either get programmed with a specific RGB Steel Blue colour value, or he’ll do it the old school way with gels. For this method he’ll dial the lights in to a 3,200K temperature. A Lee #117 Steel Blue gel will then be added to the front of them. He’ll then set the white balance of his camera to 3,200K which will give scenes this pale, green tinted wash.

Next, he’ll fill in the warmer accents either with 2,800K light, or with other warm practical sources.

A method he loves to follow is to always pre-light spaces. In other words, he’ll explain the lighting setup to his gaffer or provide lighting diagrams. These will then be set up before the main technical unit and the director arrives on set to shoot.

Laustsen also shapes his images in-camera through filtration. He often uses a ¼ Pro-Mist diffusion filter, placed behind the lens, rather than the common method of mounting the filters to the front of the lens with a mattebox. This helps to avoid ghosting or filter reflections being captured while still blooming highlights just enough to soften the digital edge. This diffusion helps maintain that painterly quality without sacrificing clarity.

Lens choice plays a central role too. Laustsen gravitates toward wide-angle lenses, usually around a 24mm, 25mm or 27mm focal length, which allows him to see more of the environment when framing characters and maintain that wide, immersive look.

He’s fond of sharp lenses like the spherical large format Leitz Thalia primes, or the Super 35 Zeiss Master Primes, or crisper anamorphics like Arri ALFAs or Master Anamorphics.

Although he of course shot his earlier work on film, in recent years he’s enjoyed working with various Arri digital cinema cameras. Pairing these wider lenses with large format cameras, like the Alexa 65 or Alexa LF, gives him a grander field of view while still preserving shallow depth of field when needed. It’s a combination that expands the set and exposes the audience to more of the location.

“Nightmare Alley we shot half of the movie 65 and the rest of it on an LF camera because the Steadicam operator could not carry a 65. So this time I said to my Steadicam Operator, ‘We have to do it all the way through.’”

If the camera is not floating around on a Steadicam it’s usually moving in another way, such as on a Scorpio or Techno30 telescoping crane. His team can set down the base of this technocrane and then use the extendable arm to move the camera anywhere within the space, jibbing up or down, swinging it side to side, or wirelessly panning the stabilised remote head left or right.

This, along with other tools like a dolly or even a Spidercam allow him to execute that smooth, gliding movement that feels almost omniscient. Whether following high pace action or drifting through intricate sets, the camera often becomes a floating observer that is precise, controlled, and dynamic.

Together,this use of stylised lighting, bold colour, wide lenses, large format sensors, diffusion, and dynamic camera movement, form the technical backbone of Laustsen’s unmistakable visual style and help him to bring the director’s fantastical, thrilling, or frightful stories to life.

CONCLUSION

Dan Laustsen’s cinematography stands as a reminder that images don’t always need to realistically or naturalistically tell stories. They can also be expressive, intentional, and emotionally charged.

Whether he’s illuminating a fantastical world, shaping tension in a horror sequence, or guiding the audience through intricate action, his work shows how technical choices can assist directors to elevate storytelling far beyond the literal. And for cinematographers, his approach offers a valuable lesson: embrace the tools, understand the craft, and don’t be afraid to let the image become a world of its own.

The Imperfect Cinematography Of Paul Thomas Anderson

The photography in acclaimed director Paul Thomas Anderson's films feels alive: not because it’s perfect, but because it’s honest. In this video, we’ll look at five different techniques that he uses in his films to build emotion not through perfection, but through presence.

INTRODUCTION

The photography in acclaimed director Paul Thomas Anderson's films feels alive: not because it’s perfect, but because it’s honest. His camera moves with a kind of quiet confidence, gliding through space in long, unbroken takes that observe rather than dictate. Shot on film, often in the anamorphic format, his images carry a texture and depth that mirror the imperfections of real life.

Over the years he’s worked with different DPs, from most of his work which was shot by Robert Elswit, to The Master photographed by Mihai Mălaimare Jr., and his recent collaborations with Michael Bauman. Throughout these different relationships certain stylistic trademarks persist.

In this video, we’ll look at five different techniques that he uses in his films to build emotion not through perfection, but through presence.

1 - LONG TRACKING SHOTS

If you had to narrow down all the filmmakers which influenced Paul Thomas Anderon’s approach into a single director, especially in his earlier work, it would be Robert Altman.

“I think what happens is that it’s in my DNA. It’s that I grew up watching those movies. It’s just informed me and informed how I want to tell stories. I learned from that and hopefully can bring something new.”

One of the visual traits of both directors is not overly chopping up their edits with quick cuts to multiple shots and angles, but rather filming more considered master shots, which often track the actions of a character, and letting those breathe in drawn out takes.

More often than not they keep their films dynamic, like their characters to be moving and for the camera to track that movement by following them.

Whereas Altman would often create frame movement by zooming the lens, Paul Thomas Anderson and his team usually used two different tools to film these long tracking shots: either a Steadicam or a dolly and lots of track.

A Steadicam mounts the camera directly to an operator via a vest with an arm and a gimbal-like stabilisation system. It gives footage a smooth, floating, fluid motion and allows the camera to move anywhere that a person is able to walk.

He’s used this for long takes, where the camera navigates through doorways, turns corners, or moves around various characters.

Because Steadicams are strapped directly onto the body the movement can come with little bumps, vibrations and small imperfections. Rather than removing these imperfections from his recent work with post production stabilisation software, he opts to keep it in. This makes the camera language feel alive, living and breathing, with a subtle handmade quality to it - something which is felt in most of his work.

Sometimes he’ll play out large portions of scenes in one, long Steadicam take. Or combine it with another technique like a crane step off, where the Steadicam op, starts on a crane platform, which then jibs down to the ground, and gives them a chance to step off the platform and continue with the rest of the take on foot.

Dolly movement on the other hand tends to be a bit smoother. A dolly is a heavy camera platform with wheels which can be pushed along tracks. Unlike a Steadicam, which can move anywhere that the operator can walk, a dolly on tracks usually sticks to one straight axis of movement.

Although there are also curved dolly tracks for doing a circular or semi circular movement.

PTA’s dolly tracking shots often follow characters as they walk or run, alongside a straight line of track.

For more stationary scenes when characters are seated he’s also used a dolly to do push ins on them, moving closer and getting inside their heads.

2 - FILM FORMATS

One thread that runs through all the movies that he’s directed is that they have all been shot on film, rather than digital cinema cameras.

Of the 10 feature films he’s made, 6 were made with a widescreen aspect ratio, while the remaining 4 used a taller frame. The size of the frame that he uses to present these worlds on screen has shifted over time, with his first 5 movies using a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, and most of his later work presented in 1.85:1.

Not only is he fond of the widescreen aspect ratio, but more specifically he likes shooting in the 4-perf 35mm anamorphic format with C and E-series Panavision anamorphic lenses.

These lenses squeeze the image horizontally by a factor of 2 to fit each frame onto a piece of film that is 4 perforations tall. This creates a higher resolution but distorted frame. This image is later desqueezed by a factor of 2 to get it back to its original proportions, which gives it its widescreen aspect ratio.

This anamorphic format also comes with additional characteristics, like more stretched, oval shaped bokeh, horizontal flares which the vintage Panavision lenses render in blue, and more distortion and focus falloff around the edges of the frame.

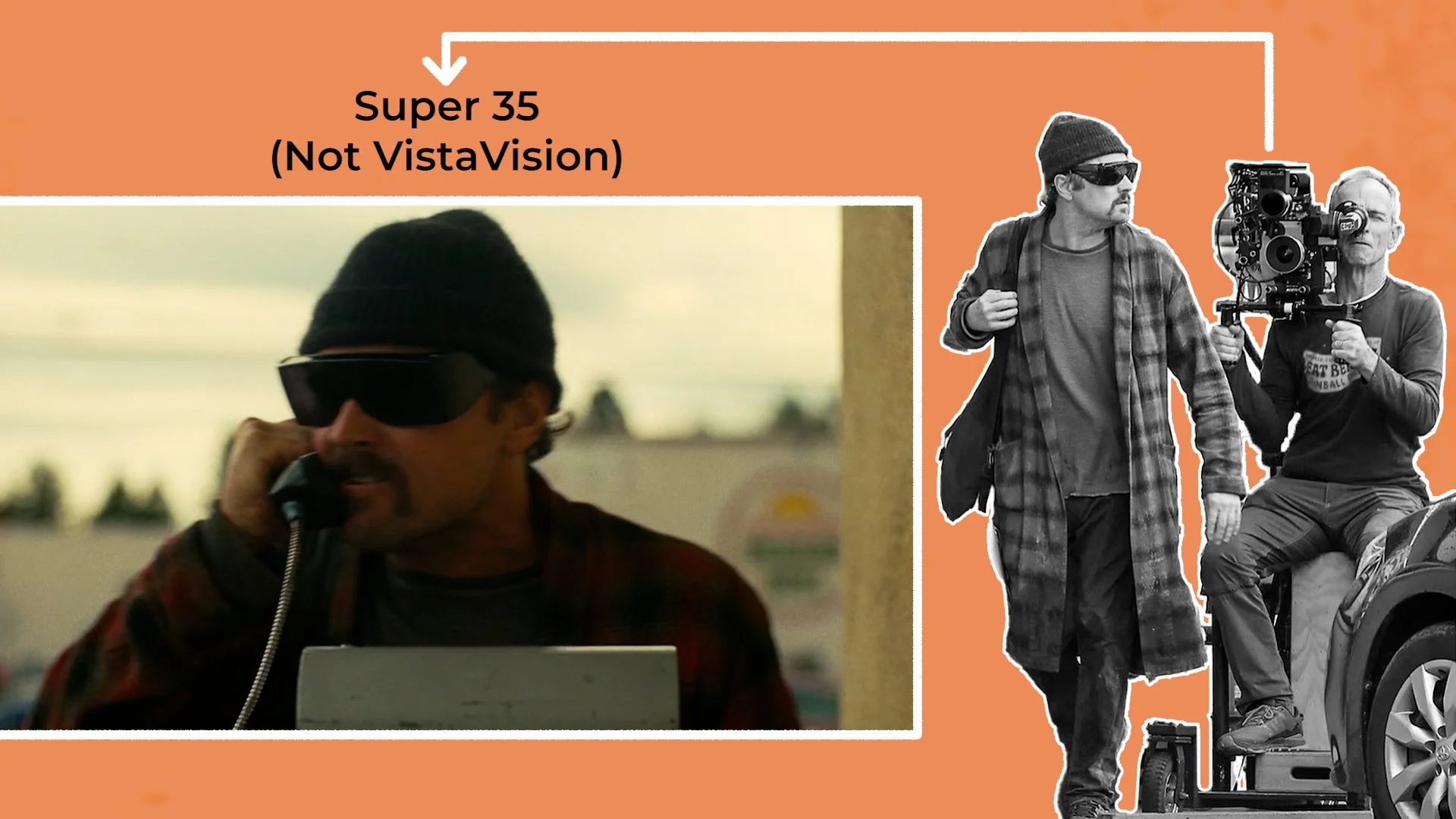

On the other hand much of his more recent work uses spherical lenses and either the Super 35 format, large format 5-perf 65mm film (in The Master), or 35mm VistaVision on his most recent One Battle After Another.

Spherical lenses create footage without an exaggerated squeeze factor, which renders images more truly, with less distortion, rounded bokeh and a squarer frame.

3 - INTIMATE FRAMING

One of the most distinctive aspects of Paul Thomas Anderson’s cinematography is how he shifts between observational wides and intimate close ups within a single sequence. His wide shots often feel detached, almost documentary-like.

When shooting in the anamorphic format he’ll often use a wider focal length for this, like a 40mm anamorphic lens, that bends the edges of the frame with distortion. This allows the viewer to observe characters in their environment to see how they occupy space and how that space defines them. But when the emotion of a scene peaks, Anderson moves in close, often with a slightly more telephoto lens, such as a 75mm, letting faces fill the frame and gestures carry weight.

This push and pull between distance and closeness reflects the emotional rhythms of his storytelling. A wide shot might hold a moment in tension, giving characters room to breathe, while a sudden close-up collapses that space, drawing us directly into their internal world.

In The Master, for instance, the switch between wide compositions, which even includes a fisheye lens shot, and tight, centered portraits of the characters, some of which were shot on a 300mm telephoto lens, creates an almost hypnotic intimacy.

4 - NATURAL, IMPERFECT LIGHTING

Paul Thomas Anderson’s approach to lighting has always leaned toward naturalism and imperfection. He’s comfortable letting the highlights from windows or even in daylight exteriors blow out, for practical bulbs to clip, and the shadows to fall away into darkness. This goes against the conventions of trying to preserve the dynamic range of what the camera captures to maintain detail in both the shadows and highlights.

Like the little vibrations and bumps in camera motion, this lighting philosophy gives his films a tactile, lived-in quality - like the images haven’t been overworked or overconstructed.

Working with cinematographers like Robert Elswit, Anderson often lights scenes using available or practical light sources like windows, candles, photographic lights, or table lamps, enhancing them subtly rather than replacing them with totally artificial setups.

Early in his career, Anderson and Elswit frequently used hard light, perhaps inspired again by some of those Robert Altman movies he grew up watching. You can see hard shadows from actors cast against walls.

Another aspect of imperfection comes from the occasional lapse in lighting continuity between shots. In There Will Be Blood, the famous oil fire sequence transitions between shots at night which were filmed after sunset lit by flames, to later shots filmed at dusk with a blue sky. There’s a similar lapse in continuity in a chase scene in his most recent work. Rather than being a negative, it’s another one of those little imperfections which gives the film its hand constructed feeling, by focusing on the chaos in the story rather than technical perfection.

5 - PRACTICAL FILMING

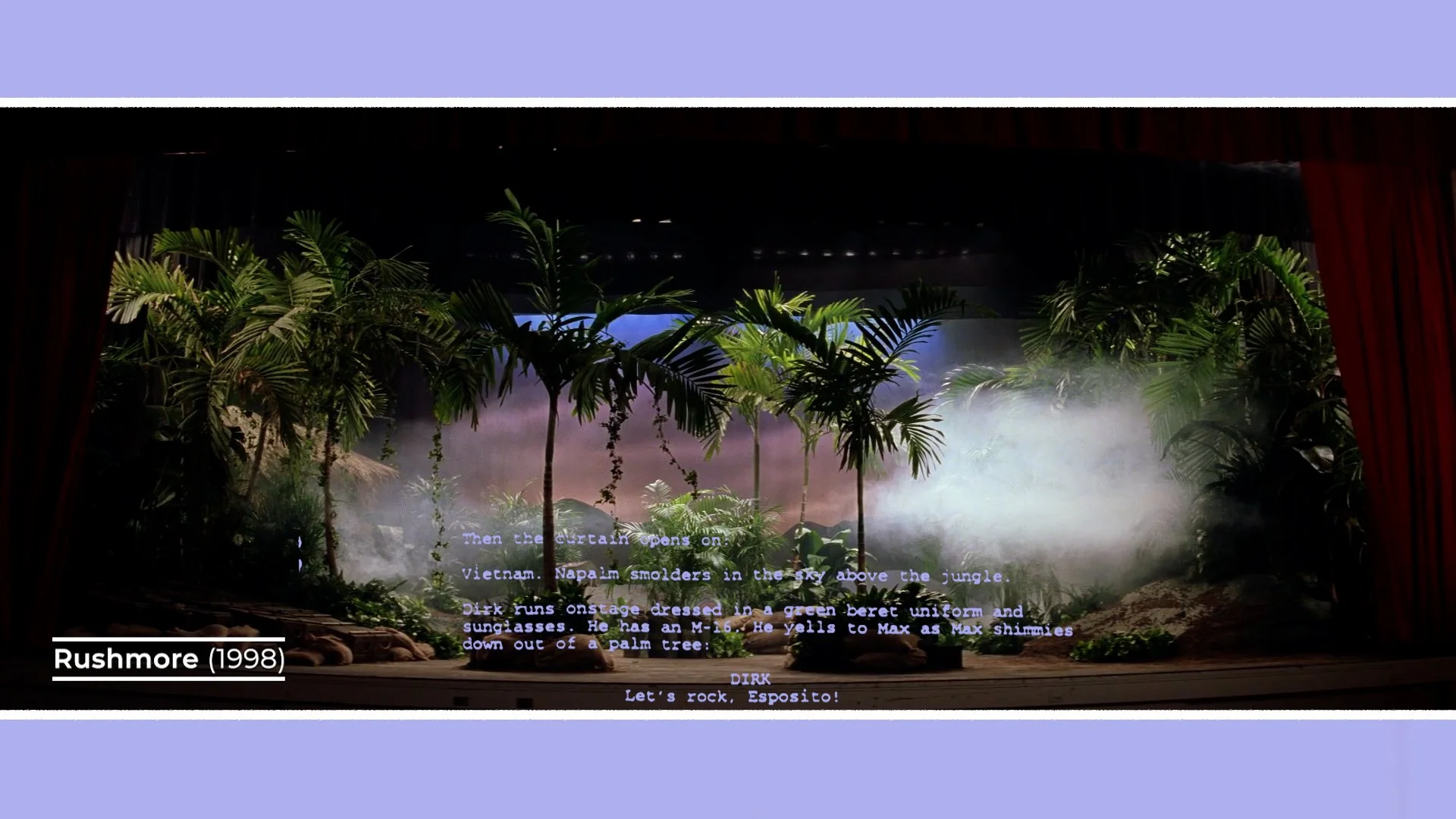

One of the most important visual aspects that gives his films their scope and sense of reality, is that he pretty much only uses real world, practical locations. He never builds sets on soundstages, well, unless the location in the script is a soundstage.

He also favors in-camera effects and practical setups over CGI, grounding even the most cinematic moments in reality. From that oil fire that we already mentioned which was shot with real flames erupting from a full-scale rig, to car crashes, stunts or confrontations. By capturing things for real, they feel real.

This preference for the tangible gives his images a sense of weight. Explosions, accidents, and even simple moments like a curtain billowing or dust hanging in the air are real phenomena happening in front of the lens. Combined with his other photographic techniques, it results in an image that feels textured, imperfect, and human - that can’t quite be replicated through digital trickery.

CONCLUSION

Paul Thomas Anderson’s cinematography is a study in controlled imperfection. His long, fluid camera moves, choice to shoot on film, clipping natural light, and his preference for practical locations and effects all point toward the same idea: that truth in cinema doesn’t come from precision, but from presence.

He builds emotion not by polishing every frame, but by allowing each one to breathe. In a time where so much of filmmaking is about control, Anderson’s images remind us that, just like in the work of his cinematic influences, beauty often lies in what’s unpredictable, fleeting, and imperfect.

How A Filmmaker’s Palette Shapes Tone

Filmmakers have three powerful colour tools at their disposal: production design, lighting, and colour grading. Each plays a distinct but interconnected role in controlling the emotional and visual tone of a story.

INTRODUCTION

If you look at footage of a scene lit by cool light and then one lit by warm light, how does each frame make you feel?

Does the whiter CCT light feel higher in clarity, more clinical, professional and emotionally distant, while in comparison the warmer light feels more comfortable, cozy and nostalgic?

The reaction each person has to colour may be highly subjective and dependent on the individual, however I think it’s safe to say that colour does have a subtle effect on how we interpret images and how we feel about them.

3 WAYS TO CONTROL COLOUR PALETTE

Filmmakers have three powerful colour tools at their disposal: production design, lighting, and colour grading. Each plays a distinct but interconnected role in controlling the emotional and visual tone of a story.

Production design establishes the foundation through the choice of sets, costumes, and props that introduce colour into the space.

Lighting then determines how those colours are perceived: whether they feel warm and inviting or cold and distant.

Finally, colour grading refines and unifies the image in post-production, determining things like saturation, contrast, and tint to create a cohesive visual identity.

1 - PRODUCTION DESIGN

The reason I list production design first is because it probably has the largest impact on the film’s palette. This is because it’s what is in front of the camera, like the colour of the walls, furniture or the props that performers interact with.

The colour of these sets can be used to support the story. Do The Right Thing positions characters against warm coloured backdrops, like red walls, or interiors full of brown and yellow wooden tones to visually amplify the scorching heat and growing tension in Brooklyn. The warm palette turns temperature into emotion as the environment itself begins to boil over with conflict.

Or, the design can lean totally the other way, in a film like Tár that uses sleek, modern interiors with cool greys, muted blues, and glass surfaces. This palette supports the titular character’s emotional detachment and need for control in a cinematic world drained of warmth and humanity.

Carefully choosing the costumes that characters wear is also an effective and sometimes more cost effective way for filmmakers to control the palette. As the actors and what they wear usually occupy a large amount of screen real estate, and it’s often easier to dress a person than an entire location.

A show that uses wardrobe colour to influence the tone and thematic interpretations of characters quite effectively is Breaking Bad. This is done by giving key characters a costume colour palette which is roughly followed throughout the series.

Walter White often wears shades of green, which perhaps hints at themes and ideas like sickness, from his cancer diagnosis, as well as his growing greed. Whereas his more reckless, dangerous, impulsive and unpredictable partner Jessie, often wears more saturated, abrasive tones, like reds and yellows.

These palettes also extend beyond wardrobe into production design, through the vehicles that they drive.

Skyler, his wife, undergoes a very subtle and gradual change in wardrobe palette throughout the series. Starting out in lighter more relaxing tones, like blue, which transitions to black in later seasons as she starts to learn more about her husband’s dark profession. I’m sure there’s also a metaphor about mourning her past life somewhere in there too.

2 - LIGHTING

Other than what is in front of the camera, another way that cinematographers can shape the colour palette is through lighting.

This is classically done by illuminating scenes with a warmer glow or with a cooler light. They can use a sliding scale of light which measures the CCT colour temperature of sources in Kelvin.

At the warm end there are light sources like candles with a reading of somewhere around 2,000 Kelvin. Or tungsten incandescent sources around 3,200K. This light can feel more romantic, nostalgic or comfortable.

Then there are more neutral 4,300K lights, like fluorescent office tubes, all the way to cooler, 5,600K daylight HMIs, cooler LED sources, or natural light at dusk. Neutral light generally feels a bit more clinical, and appropriate for professional settings like offices, or hospitals, while the cooler we go the more emotionally detached, or even lonely the tone may feel.

Although of course these emotional interpretations are highly reliant on the subject of the story and mindset of the character. Sometimes specific interpretations of colour theory can remain ambiguous and rather create an overall feeling or tone that runs throughout the film as a whole.

For example, Euphoria is lit with vivid palettes which tend to use either lighting on the more extreme sides of the CCT spectrum or colourful RGB light. These support the emotionally elevated states of the teenage characters. Every part of their young adulthood is intensely and passionately experienced in a heightened way.

Similarly, Ballad Of A Small Player was lit with a vivid neon palette that mixed different types of light sources of different colours: from steely, saturated teal, to warm tungsten practicals and real world RGB signage of all colours.

Pushing the lighting into saturated RGB tints and away from the regular CCT spectrum of light, visually supported the explosive, manic, panic induced mindset of the gambling addict protagonist.

Contrast this with the character in I, Daniel Blake, whose plain life, drained of glamour, is depicted though far more realistic, neutral lighting with evenly balanced colour temperatures that don’t push an unnatural spectrum of colour.

3 - GRADING

After filmmakers have dressed their location, lit and shot it, the final step where they can determine the direction of the palette is during the colour grade.

Although the famous tongue in cheek saying goes, ‘just fix it in post’ it’s normally not advised to stretch the look too far beyond what has been recorded. This is because by this stage the palette of the lighting and set are of course burned into the image.

However, there’s certainly still room at this stage to subtly push the look of the colour in different directions.

The Matrix did this by colour timing scenes that took place in the undesirable digital world in the most unappealing colour they could think of. They added a green tint, especially in the mid tones, to all the scenes that took place in the Matrix world and also digitally enhanced the skies to make them more artificial and white, removing blue.

These little tweaks moved the palette in this artificial world away from a real colour space, giving images the feeling that something was slightly off, a bit grimy, unnatural and unpleasant.

Then, when cutting to scenes that took place in the real world, filled with a dark reality, they kept the colour correction and tints neutral, with a subtly cooler, shadow laden look.

Grading software also has other tools beyond adding a colour tint. For example, a key decision during the post production process is deciding on the level of saturation and contrast - which determines how vivid or washed out the colour feels.

We mentioned the lighting of Ballad Of A Small Player, well part of what supports this is how the footage was treated during the grade. They pushed the contrast and saturation to the extreme. This led to highlights clipping, shadows getting crushed and skin tones that were at times overly saturated and right on the edge of breaking apart altogether.

If you bring down the saturation and contrast it loses some of its manic visual tone and tense emotion.

When it comes to grading, a trick that cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto used when working with colourist Yvan Lucas in Baselight grading software is to create different LUTs, looks with different colour, contrast and saturation levels, that were based on actual photochemical filmic techniques.

For example a Technicolor ENR-process look that is contrasty with particularly rich blacks but subdued colors, a look that replicates Kodak film negative printed on Kodak print stock - which has more saturated, natural tones, or a vintage Autochrome look which is less saturated with colours emulationing the early film stock.

They then apply these different looks to different scenes depending on their emotional content and what is happening in the story.

Such as using the more saturated Kodak look for a magical, transcendental moment, then cutting back to reality on the same angle but with a more desaturated look. Or for a pivotal scene wrought with destruction, guilt, shock and confusion, applying the ENR look that is contrasty with heavy shadows but desaturated colors.

Prieto used this same idea on Barbie, using a more saturated, three-strip Technicolor style LUT for more playful scenes in her larger than life, fantastical world, and using a desaturated look with less vibrant colour and skin tones for the more depressing, less spectacular real world which was stripped of magic and joy.

CONCLUSION

Colour isn’t just something we see, it’s something we feel. Whether it’s through the sets and costumes that shape the world in front of the camera, the lighting that determines how those colours come to life, or the final grade that unifies it all, filmmakers use colour as a quiet language of emotion.

A shift from warm to cool light can turn comfort into isolation. A change in wardrobe can track a character’s internal decay. And a subtle tint in the grade can transport us into an entirely different dystopian world.

What’s remarkable is that these changes often work subconsciously, without us being aware that the filmmakers are subtly manipulating how we feel about the story. We don’t have to notice the hue of a wall, the colour of a costume or the tint of a light to feel their effect.

Because when colour is used with intention, it doesn’t just decorate the frame it deepens our connection to the story. And that’s the real power of a film’s palette: to shape not just what we see, but how we experience the world on screen.

Cinematography Style: Philipe Le Sourd

In this episode of Cinematography Style, we’ll explore the visual language of the French DP and the filmmaking gear and techniques he selects to make it happen. Examining how his use of texture, light, and composition creates a cinematic world that’s both romantic, natural and restrained.

INTRODUCTION

In the world of cinematography, Philippe Le Sourd’s images feel like paintings in motion that are elegant, deliberate, and deeply atmospheric. From the soft, desaturated candlelight of The Beguiled to the poetic grandeur of The Grandmaster, his work captures not just how a scene looks, but how it feels.

In this episode of Cinematography Style, we’ll explore the visual language of the French DP and the filmmaking gear and techniques he selects to make it happen. Examining how his use of texture, light, and composition creates a cinematic world that’s both romantic, natural and restrained.

BACKGROUND

Le Sourd has been working as a director of photography since the 90s. While he began his career shooting for French filmmakers in his home country, he has since collaborated with a wide range of international directors. From Ridley Scott to Wong Kar-Wai - which earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography - and more recently through his ongoing collaborations with Sofia Coppola.

PHILOSOPHY

Before thinking about the technical side of filmmaking, like camera gear, the first point of departure between a director and a cinematographer is usually to begin building an idea or imagining of the visual language for the film.

This could be a singular visual idea, such as needing the overall palette to feel more neutral or desaturated throughout the movie, or, more often than not, a collection of different visual vocabularies that become a language, like choosing an aspect ratio, a style of lighting, a softer texture to the lensing, an approach to the framing, or a cool-warm palette duality.

Le Sourd acknowledges that the process for developing this visual language changes depending on the director he’s working with.

For his collaborations with Sofia Coppola - the script and underlying emotions that the characters are experiencing are the first points of reference.

“She doesn’t want to have the image too strong compared to the emotion. So, you try to match very closely what could be the emotion and what the format should be for the film.”

They’ll build this look and tone using research, references and camera tests. He’ll start by doing research, such as looking at examples of Civil War imagery on The Beguiled.

They’ll then go over some more specific visual references, which are often from photographers, such as a still from Saul Leiter with a bright, blowing background that influenced the look of Priscilla’s interiors, or the portraits of Julia Margeret Cameron with their washed out tonality of grey which informed The Beguiled.

Based on this idea he’ll then usually conduct more technical gear tests of lenses, cameras and filmstocks to arrive at the look ahead of shooting.

Since Coppola writes her own screenplays, which often means living with the material for years before it is shot, she’ll usually have a broad idea of how to represent each scene, such as whether the camera is further or closer to characters, or whether it plays out in a single shot.

For more complex scenes with a greater number of characters they’ll work together to create a list of shots on set based on the blocking. They like to do this by using a still camera to take photos from different angles during the rehearsal, then decide on which of those shots are needed. Trying to visually simplify things by not overshooting too much coverage.

Other directors, like Ridley Scott, work differently with a more straightforward, production oriented approach and a producer’s eye.

“I don’t think he’s the type of director who has a discussion about the visual language. I think he’s about setting it up, the number of shots and schedule. He will tell you very directly if he likes it or not.”

They didn’t decide on a visual style going in and rather let the film’s design be determined by the locations he selected around the south of France - which built in a large part of the look. With warmer, earthy exteriors lit by natural, dappled light under oak trees.

Working with Wong Kar-Wai presented yet another different collaborative relationship. In a highly unusual working style, they went into production without having a fully written screenplay. Instead, Kar-Wai would work things out as he went along. Writing a few pages based on a character, a location, or a story idea - which Le Sourd would then shoot. The director would then review the rushes and either write a few new pages, or reshoot the scene they had already shot, but this time perhaps with a new narrative idea, a different actor, or with a freshly dressed set.

“It’s really step by step and you never know where you will go. You have no idea. About the script, the cinematography and the actor.”

The challenge of creating the visual language became largely about how to maintain continuity over a production timeline that eventually lasted around 3 years. To create a coherent look he’d keep extensive notes about all the gear he used, and how he set it up and positioned it for each scene. So if he needed to come back to a space he could recreate a look.

In this way, they cobbled The Grandmaster together by slowly adding different segments until they finally reached a product with a complete story.

All of these different approaches for the various directors he worked for meant he needed a range of technical tools and techniques which he could use to create each movie’s visual language.

GEAR

Although as we’ve seen Le Sourd’s work doesn’t fall neatly into one style, but is rather created afresh based on each script and director he works with, there are a few characteristics which he carries through.

He tries to not do too much with the camera by creating a language which is naturalistic, yet is slightly elevated for cinema, with often underexposed, darker lit, shadowy interiors.

I’ve also noticed that the movies he shoots often push one of two looks.

Either, one, a cool and warm colour palette with a good level of filmic saturation. Or, two, a more desaturated look which maintains contrast with large amounts of dark shadow.

This first look can be seen in films like A Good Year, Seven Pounds, The Grandmaster and On The Rocks.

He creates this cool-warm look partly by using lights with different colour temperatures. If we look at a few examples of this lighting style you can see a common theme emerge - most of the palette is cool, with a few accents of warmth.

The first step to this look is shooting with a cool white balance. Since almost all of his work was shot on film, he’d usually select a tungsten balanced film stock for these interiors - such as Kodak 500T.

These stocks have a colour temperature of approximately 3,200K - which is what you could set the camera to if shooting digitally.

Next, he'd use lights to create a level of ambience - which is like an overall soft fill that envelops the location. This is done with cooler light set to somewhere around 4,300K or 5,600K.

He then uses practical sources that can be seen in the shot, like candles or lamps with incandescent bulbs with a warm colour temperature, such as 2,800K. Creating little warm hotspots that offset the cool look and create a colour contrast.

Sometimes, instead of it being a practical, the warmth comes from using a warmer key light on the actors’ faces while keeping the background ambience lit by a cooler source.

With the capabilities of grading software like Baselight, he can combine old school 35mm film capture with new school colour manipulation. Pushing more of a cyan look into the cooler tones.

He also likes pushing a warm look for exteriors - which is probably mostly done in the grade. And, especially in films like The Grandmaster, giving interiors an overall warmer palette, by only lighting with warm, probably tungsten, sources - and removing his cool ambient fill source.

Remember we mentioned he likes shooting camera tests ahead of production. Well, a colour workflow he has used is to give those tests to a colourist, who will then build a custom show LUT. This LUT can be applied to dailies - which Le Sourd views on an iPad on the Copra app. He can use this app to make grading notes or corrections which his colourist can then implement.

The second more desaturated look which I mentioned he’s pushed mainly on his more recent work on period dramas with Sofia Coppola, like The Beguiled and Priscilla.

A technique he likes to use is pull processing film by one stop. This is where you overexpose the film. So if he’s shooting 500T, a 500ASA film, he’ll rate it at 320ASA, a stop brighter.

When the overexposed film is processed it is then underdeveloped in the lab to get it back to its correct exposure. Pull processing is done to retain more detail in the shadows and in the highlights and reduce the film grain. It also decreases the saturation - which created less vibrant colours in The Beguiled.

He created a similar desaturated look on Priscilla - however this was done digitally in post production rather than photochemically.

Le Sourd almost only shoots features on 35mm film - with the one exception being Priscilla - which for budgetary reasons was shot digitally on the Alexa 35. Opting for the more classically traditional Super 35 format over using large format cameras.

Unlike the trend of using wide angle lenses for everything, Le Sourd prefers to select more medium focal length lenses - most commonly a 40mm, 50mm, or 75mm. He also shies away from anamorphic lenses, preferring to shoot with spherical, Super 35 glass and then crop to widescreen aspect ratios if they’re required.

Most of his films are serviced by Panavision, on their spherical prime lenses. From the Primos, to the PVintage, or the Super Speed or Ultra Speeds.

Although on The Grandmaster he selected Cooke S4s and used an Angenieux Optimo zoom for some of the telephoto shots.

CONCLUSION

Le Sourd’s cinematography is a study in restraint: a reminder that visual beauty often lies in what’s left unsaid. Whether working within Coppola’s delicate emotional worlds or Wong Kar-Wai’s improvisational chaos, he adapts his craft to serve story and tone above all else.

His images feel timeless not because of flashy technique, but because of how quietly they observe character and emotion.

How Sofia Coppola Shoots A Film At 3 Budget Levels

Let’s take a look at Lost In Translation ($4 million), Priscilla ($20 million) and Marie Antoinette ($40 million) to see how Sofia Coppola used the resources she had to tell powerful stories about women protagonists framed by desaturated, pastel palettes, a mature restraint, and an almost musical sense of stillness.

INTRODUCTION

Sofia Coppola’s films feel like quiet daydreams. With worlds of isolation, luxury and honest human relationships, captured through a lens of melancholic beauty.

Throughout her career she’s directed films at various budgets, from the indie level, semi-gun and gun Lost In Translation, to the larger scope but time pressed Priscilla, all the way to the luxury-laden high budget Marie Antoinette.

Let’s take a deeper look at each of these three productions to see how Sofia Coppola used the resources she had to tell powerful stories about women protagonists framed by desaturated, pastel palettes, a mature restraint, and an almost musical sense of stillness.

LOST IN TRANSLATION - $4 MILLION

A core component of Coppola’s work is that not only is she a director but also a writer. Having written the screenplays of all of the features that she had directed.

While traveling and spending long stretches in hotels, Sofia Coppola began imagining a story about two lonely Americans adrift in Tokyo - which stood as a microcosm of a relationship.

She wrote the Lost in Translation screenplay over six months: a quiet exploration of disconnection, misunderstanding, the camaraderie between foreigners, fleeting moments of intimacy and everything lost between the lines.

To get the approximately $4 million production budget, Coppola and her team pursued more of an independent model of financing than a studio style one - where a single company buys and owns the film. In this approach, the filmmaker sells distribution rights separately across different international territories, using those presales to finance the film.

Because the film was not controlled by a single studio or U.S. distributor it allowed her more creative control and gave her the final cut.

The relatively low budget allowed them to shoot the short length, approximately 70 page feature script over 27 days. It also meant they had to use a smaller technical crew and a more compact gear package.

Coppola and her DP Lance Acord embraced these technical limitations by adapting a production style characterised by working with the real world environments which are available - rather than trying too hard to construct a world which isn’t real though built sets, or supreme control of lighting.

They felt they could create a visual middleground by embracing a similar approach to other movies with this real world feel like Festen or The Anniversary Party that were shot on the digital video format which was still in its infancy, but elevate this look by instead shooting on 35mm film and subtly supplementing light in these real world environments when needed.

Since their low budget meant it wasn’t possible to lock off large sections of the city, they filmed most of the Tokyo exteriors in a run and gun, semi-documentary style (allegedly without a shooting permit). This allowed them to get incredible shots of the actors walking around at iconic locations like Shibuya crossing - with real people as extras in the background.

To get away with filming in this style they shot handheld with a lightweight 35mm camera, and a skeleton crew of Acrord, Coppola and his 1st AC Mark Williams, pulling on an old school manual follow focus judging distance by eye - without any monitors in sight.

They used two camera bodies on the production - mostly the small 35mm Aaton 35-III which was used for handheld or other scenes, or the larger Moviecam Compact which was needed for close quarter applications like shooting in hotel rooms or bathrooms where the Aaton made too much noise.

He paired these cameras with a set of Zeiss T/1.3 Superspeed primes - mostly shooting on the 35mm focal length, which gave the same perspective as that of a tourist’s point and shoot camera.

They also carried a long Angenieux Optimo zoom for picking actors up in public spaces from far away with the more compressed telephoto lens.

Even for locations which they did have more control over, like the solo hotel room scenes with Johansson, they employed a similar, technically minimalist approach. Only Coppola, Acord and Johansson were allowed in the room - with occasionally the wardrobe, make-up and AC allowed in to check all was going well. Acord would operate and pull focus, often without even rolling sound, to give these scenes a handheld, intimate feel.

Although much of the framing and shot selection was worked out in the space, they did on occasion jot down some notes detailing character movement and shots, especially for sequences which involved more complex movement.

True to this real world approach Acord used lots of natural light. He shot all night exteriors using only the real available mixed light sources in the city, like sodium vapour, neon and lanterns, without adding any additional film lights. To do this he shot night exteriors on Kodak’s high speed, lower contrast 500T film stock 5263. While he used a 320T 5277 stock for daylight scenes or interiors.

The fast Superspeeds allowed him to shoot wide open or at T/2 to have enough light for some of these night exteriors. However, in the more populated and brightly lit areas like Shibuya he’d actually stop down to around T/4 or T/5.6 and underexposed to keep a low contrast, low saturation look.

For some interiors, like the subway or arcade they’d rely mostly on the location’s available fluorescent tube lighting. However, Acord did get his team to supplement the arcade scene with a few 4 foot 4-bank Kino Flos, with cool daylight bulbs.

Or the hotel bar, which was mainly lit by warm practical lamps, supplemented by some added film lanterns that were the same colour temperature.

Instead of cutting and shaping light with large 4x4 floppies, diffusion frames or black flags and lots of c-stands, which may happen on a traditional industry set, his electricians would just use little off-cuts from diffusion gels and black wrap, which they’d rig on the light with croc clips. Which is much faster and leaves a minimal gear footprint.

Coppola was able to pull off this beautiful film on its relatively low budget, by writing a shorter screenplay that focused mainly on two actors, which largely took place in one controllable hotel location. And then shooting most of the exterior scenes which would’ve usually needed more control, permissions and budget, in a run-and-gun style with a skeleton crew, to give the story its feeling of authenticity and scope.

PRISCILLA - $20 MILLION

Lost In Translation’s 70 page script was made for $4 million. So when you hear that Priscilla’s 80 page script was budgeted at $20 million - you may imagine that this would come with much more time and control for Coppola.

However, since it was a period drama, based on IP, with a larger art department and wardrobe scope, they were actually only able to get 30 shoot days out of the budget.

Also, if you factor in inflation that $20 million would be roughly the equivalent of a $12 million budget at the time when Lost In Translation was shot.

Coppola wrote the screenplay about Priscilla Presley’s life between the ages of 15 to 27, based on her memoir Elvis and Me. The film plays out through Priscilla’s eyes and chronicled the ups and downs of navigating a complex relationship - with both its dark and lighter side.

Before production started, she had to cut out 15 pages from the initial script in order to limit shoot days and make the budget work.

Funding was sourced by Italian producer Lorenzo Mieli through the shareholders at Fremantle, under the name of a production company called The Apartment Pictures.

To keep costs down and best utilise the budget they shot in Toronto and built sets on soundstages for the Graceland interiors.

Coppola teamed up with one of her regular cinematographers Phillipe Le Sourd to create the film’s visual tone. They stayed away from recreating iconic historical moments in a photocopy style, and rather created a language that felt like a memory that was specific to the film and Priscilla’s point of view.

A reference that informed this was a backlit, black and white photograph of a woman in silhouette by Saul Leiter. Many frames lean into this look, framing characters against a strong, single source backlight such as a window which blew out with overexposure. This backlight often washed out the shadows and gave images a lower contrast - which Coppola has always been a fan of.

Another budget compromise they had to make was gear related. Le Sourd, who had only ever worked on film, was forced to select a digital cinema camera. He chose an Alexa 35 with Panavision Ultra Speed and Super Speed lenses.

Although they did use little snippets of 16mm 250D stock shot on a Bolex H-16 and Super 8mm 50D or Ektachrome 100D to create period appropriate home video style footage.

Coppola and Le Sourd found ways to push the tone with the cinematography. A long, slow zoom out on an Angenieux HR 25-250mm lens created a sombre feeling of alienation.

They used a handheld camera for emotionally heightened moments.

A shifting orange, red neon lighting from Skypanel S360s and other LEDs inside the room gave the scene a feeling of love, living, blood and hurt.

Overall, Coppola used Priscilla’s budget to tell an intimate portrait of a relationship through the experiences of its protagonist.

The period setting required larger art department set builds and greater scope production design, a larger cast and greater control over technical setups and locations - with no room for run and gun shooting.

MARIE ANTOINETTE - $40 MILLION

In a similar vein to Priscilla, Marie Anoitnette was Coppola’s first big introduction to making a period film about a well known figure in history.

She based the script on the book Marie Antoinette: The Journey by Antonia Fraser - which chronicled her life leading up to the French Revolution. Coppola sought to create an impressionistic interpretation of Marie Antoinette which would let the audience get lost in her luxurious world and imagine what it would be like to experience life in Versailles during that time.

To create this larger than life scale portrayal that was full of visual set pieces, an enormous wardrobe department and meticulous, audacious production design - required a larger budget of approximately $40 million (somewhere around $65 million when adjusted for inflation).

To raise so much capital required backing from one of the big studios: Columbia Pictures.

All it takes is watching the film to see where some of that spend ended up. The film is laden with a large cast and loads of extras all kitted out in truck loads of fabulous wardrobe, set against opulently designed sets and locations which included access to the real Palace of Versailles.

All of this takes lots of planning, crew, resources and time. They were therefore able to shoot from January to April, far longer than the approximately 30 days she had for her other productions.

Again, she worked with DP Lance Acord to develop a visual approach. Coppola didn’t want to fall into the conventions of period filmmaking being dark, cold, and neutral. Instead they wanted to reflect her luxury environment by making it brighter and more pop with a colourful, pastel palette.

Another convention they pushed back against was a widescreen aspect ratio. Instead opting to shoot the film in the taller 1.85:1. This gave frames more height and meant wides could capture more of the architecture and high ceilings.

Lighting these large spaces in a more high-key style required a larger team of technicians and more gear. For example, for day scenes his team built a lighting platform outside the windows, or used crane lifts, and pushed through rows of 12K HMIs. The windowpanels out of the frame were covered with a thick diffusion. This created giant, soft panels of light.

Unlike the electrical team on Lost In Translation who would use natural light, black wrap and offcuts of diffusion, the lighting in Marie Antoinette was much more traditional and larger in scale with a full collection of frames, flags and lights.

For night interiors Acord tried to create a candlelit look using film lights. His team built different strings of bulbs - with either 60 watt or smaller 15 watt bulbs - that had a colour temperature of 2,800K.

Some of these lines were rigged onto or around styrofoam balls, or 4x4 or 8x8 frames with diffusion. They also used rope lights, placed on tables or actors' laps to give soft light from below.

These cast a soft ambient glow across the spaces and gave enough exposure to be able to shoot on the 500T 35mm film stock used for interior and night scenes. This had a slightly softer contrast than the Kodak 250D stock that they used for exteriors which was more vibrant and saturated.

Like on Lost In Translation his camera package consisted of a lightweight Aaton which he paired with an Arricam.

He used old Cooke Speed Panchros from the 50s and 60s which were rehoused by Van Diemen. This vintage glass gave a soft diffusive quality to images - which complemented the pastel look, and lowered the contrast with a veil effect when they were shot against a bright backlight.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, the size of a film’s budget shapes everything: from the scope of production design, costume and locations, the size and notoriety of the cast, to the crew size and gear choices, and, perhaps most importantly, the time and level of control you have on set.

As Coppola’s work shows, working within those limits isn’t just about money; it’s about adapting your approach to tell the best story with the resources you have.

What A Production Designer Does On Set: Crew Breakdown

In this video, we’ll break down what a Production Designer does on set to bring a film’s visual language to life.

INTRODUCTION

Every frame tells a story. Not just through the actors, lighting, or camera movement, but through the world those elements exist in: the color of the walls, the texture of the furniture, or the objects which actors hold. The look of the space shapes how we feel about the story unfolding before us. Behind that world is one key creative: the Production Designer.

In this video, we’ll break down what a Production Designer actually does on set, how they collaborate with the director and cinematographer to bring a film’s visual language to life, and why their work begins long before the camera ever rolls.

ROLE

Production design is the backbone of what filmmakers call mise-en-scène. The phrase comes from theatre (literally meaning “putting on stage”) and describes everything that appears within the frame and how it’s arranged. For example, how the set or location looks and what objects or props are placed in that space.

It’s the job of the Production Designer to create mise-en-scène which transforms abstract ideas or places described in the script into physical reality, giving the audience something to see and feel.

They do this, as head of the Art Department, by translating the director’s vision, into the film’s tangible shooting environments.

Since there’s an expectation that these sets will be mostly ready to shoot by the time the crew arrives at each location - the Production Designer and their team will need to put in a lot of work in pre-production.

They’ll start by reading the script, researching, talking to the director, cinematographer and costume designer and conceptualising the film’s main environments. Often creating a mood board, sketches, or some kind of pre-visualisation document that depicts the overall style, color palette, and aesthetic influences.

The design required could change vastly depending on the subject matter or tone the director wants. Is the tone of the film whimsical, comedic, light, neat, symmetrical and theatrical, or does the movie need a realistic, darker, neutral, historically accurate set?

Some scenes may want to adhere to a strictly limited colour palette which feels almost cartoonish. Others may want a more tonally subdued or neutral environment, a space which is bright and saturated, or to create a subtle feeling of unease and sickness by dressing in objects which are off green or have a yellow tinge.

Another idea is to lean thematically towards either a warmer, homely space, with wood, warmer colours and softer textures, or create a cooler set, with hard edges and glass, which is more sparsely dressed.

As well as creating a feeling or tone, production design can also be used to more literally inform the audience or tell the story. This could be done by creating a realistic environment of an historically accurate and researched space. Or by adding details which hints at the character’s life, such as a photo of their family, or a placard that signifies their job title.

Often this will be explicitly described in the script, however these ideas may also be put forward by the Designer.

With these concepts in mind they’ll liaise with the production team, the director, location scout, cinematographer and sometimes other crew, to come up with physical spaces which work on an aesthetic, budget and practical level.

This will usually be a real world location, but in some instances may have to be a set built on a soundstage.

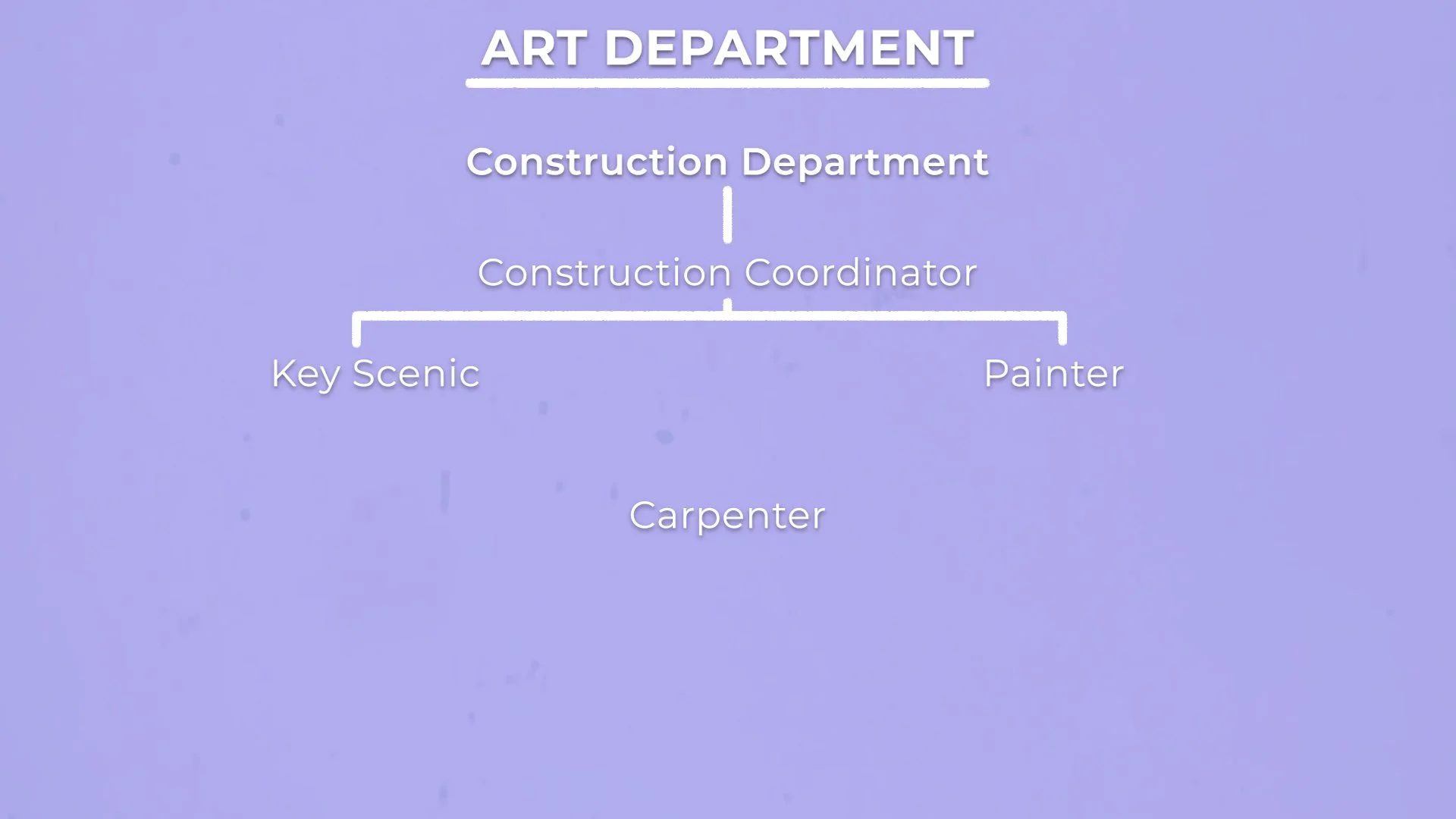

The design of the film is usually broken into a couple of elements. One, set design, which is dressing the physical location, such as painting walls or selecting furniture. Two, props, which are key objects on the set integral to the story, or which the actors interact with.