Do Cinematographers Like Lens Flares? Textured vs Clean Images Explained

INTRO

“I can’t stand flares. I find any artefact that is on the surface of the image a distraction for me. The audience or I’m then aware that I’m looking at something that is being recorded with a camera.” - Roger Deakins, Cinematographer

“If the light shone in the lens and flared the lens that was considered a mistake.I feel particularly involved in making mistakes feel acceptable by using them. Not by mistakes or anything but by endeavour.” - Conrad Hall, Cinematographer

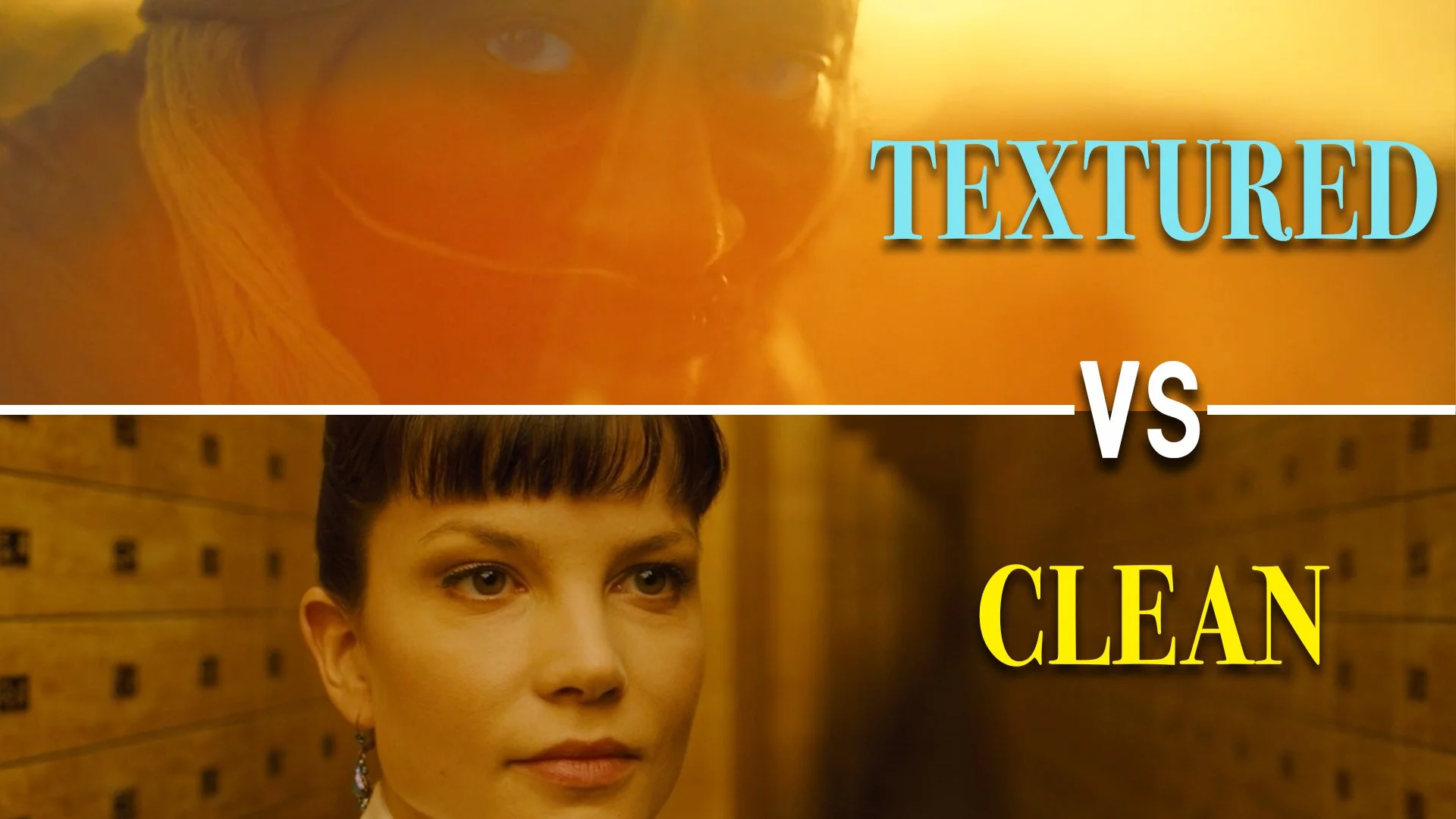

When it comes to the question of whether clean or textured images should be favoured, cinematographers are generally split into two different camps. Some see their goal as being to create the most pristine, cinematically perfect visuals possible, while others like to degrade the image and break it down with light and camera tricks.

Before we discuss the pros and cons of clean and textured images, we need to understand some of the techniques used by cinematographers that affect the quality of how an image is captured. Then I’ll get into the case that can be made for clean images and the case that can be made for textured images and see which side of the fence you land on in the debate.

WHAT MAKES AN IMAGE CLEAN OR TEXTURED

When cinematographers talk about shooting something that looks clean, they are referring to an image which has the subject in sharp focus, which is devoid from any excess optical aberrations, video noise, grain or softening of the highlights or bright parts in the frame. Some cinematographers however like to introduce different kinds of textures by deliberately ‘messing it up’.

The easiest identifiable optical imperfection is the lens flare. This happens when hard light directly enters the open glass section at the front of a lens and bounces around inside the barrel of the lens off of the different pieces of glass, which are called elements.

So to get a lens flare, cinematographers use a backlight placed directly behind a subject or at an angle that is shined straight at the lens. A common way of doing this is to use the sun as a backlight and point the camera directly at the sun.

In the past, flares were often seen as undesirable so a few tools were introduced to get rid of them. To prevent a flare you need to block the path of any hard light that hits the lens directly. A mattebox is used not only to hold filters but also to block or flag light from hitting the front element. A top flap and sides can be added to a mattebox to cut light, as can a hard matte - which clips inside the mattebox and comes in different sizes which can be swapped out depending on how wide the lens is.

If a shot is stationary and the camera doesn’t move, the lighting team can also erect a black flag on a stand to cut light from reaching the lens.

On the other hand, a trick some use to artificially introduce a flare when there isn’t a strong backlight is to take a torch or a small sourcy light like a dedo and hit the lens with it from just out of shot.

Different kinds of lenses produce different kinds of flares, which are determined by the shape of their glass elements, the number of blades that make up the aperture at the back of the lens and the way in which the glass is coated. Standard, spherical lenses have curved, circular elements that produce round flares that expand or contract as the light source changes its angle.

Anamorphic lenses are made up of regular spherical glass with an added section of concave glass that vertically squeezes the image. It is then de-squeezed to get a widescreen aspect ratio.

Because of this, anamorphic lenses produce a horizontal flare that streaks across the frame. The Panavision C-Series of anamorphic lenses are famous for producing a blue anamorphic lens streak which is associated with many high end Hollywood films.

The glass elements inside a lens have different types of coatings. Modern coatings are used to decrease artefacts and limit flooding the image with a haze when the lens flares.

As technology has improved these coatings have gotten progressively better at this and therefore more modern lenses produce a ‘cleaner’ image. One way that cinematographers who like optical texture get around this is to use vintage lenses that have older coatings that don’t limit flares as much or bloom or create a subtle angelic haze around the highlights. You even get uncoated lenses for those that really want to push that vintage look.

Another option to soften up an image a bit is to use diffusion filters. These are pieces of glass that are placed inside a mattebox and create various softening effects, such as decreasing the sharpness of the image, making the highlights bloom and softening skin tones.

Some examples of these filters include Black Pro-Mists, Glimmer Glass, Pearlescents, Black Satins, Soft FX filters - the list goes on. They come in different strengths, with lower values, such as an eighth providing a subtle softness and higher values providing a heavy diffusion.

Some cinematographers even go more extreme by using their finger to deliberately smudge or dirty up the front of a filter.

A final way of introducing texture to an image is with grain. This can be done either by shooting on a more sensitive film stock, like 500ASA and push processing it, by increasing the ISO or EI on the camera, or by adding a film grain effect during the colour grade in post production.

THE CASE FOR TEXTURED IMAGES

“What lenses? Should it be sharp? Should it have flaws? Should it have interesting flares? I always try to be open to everything.” - Linus Sandgren, Cinematographer

Now that I’ve listed all the ways that an image can be messed up by cinematographers, let’s go over some reasons why anyone would actually want to do this in the first place.

Up until about the 1960s or 1970s, the idea of intentionally degrading how an image was captured wasn’t really prevalent. However, movements like the French New Wave or New Hollywood rebelled against capturing a perfect representation of each story and intentionally used things like flares to do this.

Producing optical mistakes from a more on the ground camera created an authenticity and grittiness to the images in a similar way that many documentaries did.

In different contexts, optical aberrations, like lens flares, have been used to introduce different tonal or atmospheric ideas. For example, Conrad Hall went against the Hollywood conventions of the time and embraced flares on Cool Hand Luke to create a sense of heat from the sun and inject a physical warmth into the image that reflected the setting of the story.

Some filmmakers like deliberately using lower gauge film such as 16mm or even 8mm to produce a noisy, textured image. Often this is perceived as feeling more organic and a good fit for rougher, handheld films.

Textured images with a shallow depth of field also feel a bit dreamier, and can therefore be a good tool for representing more experimental moments in a story or to portray a moment that happened in the past as a memory.

Since the digital revolution, many DPs have taken to using diffusion filters and vintage lenses on modern digital cinema cameras - to balance out the image so that it doesn’t feel overly sharp.

Degrading the image of the Alexa by shooting at a higher EI, like 1,600, shooting on lenses from the 1970s, or using an ⅛ or a ¼ Black Pro Mist filter, are all ways of trying to get the more organic texture that naturally happened when shooting on film back into the image.

THE CASE FOR CLEAN IMAGES

“Digital cameras were able to give us a beautiful, very clean, immersive image that we were very keen on…3:13 It almost translates 100% what you are feeling when you are in the location.” - Emmanuel Lubezki, Cinematographer

On the flipside, some DPs seek a supremely clean look that pairs sharp, modern glass with high resolution digital cameras.

One reason for this is that clean images better transport the audience directly into the real world, and present images in the same way that our eyes naturally see things. Clean images are regularly paired with a vision that needs to feel realistic.

These cinematographers see any excess grain or aberrations as a distraction that pulls an audience out of a story and makes them aware that what they are seeing isn’t reality and is rather a visual construction.

When light flares across a lens it’s an indication that the image was captured by a camera and may disrupt the illusion of reality.

Sometimes filmmakers also want to lean into a clean, sharp, digital look for the story. It’s like choosing to observe the world directly, in sharp focus, rather than through a hazy, fogged up window.