5 Trademark Christopher Nolan Camera Techniques

INTRODUCTION

Christopher Nolan is probably the most well known director working today. His movies use non-linear storytelling, practical effects, powerful, immersive music and impactful setpieces to tell subjective, human centred stories.

His filmography has been split by his work with two different cinematographers: his earlier films with Wally Pfister and his more recent movies with Hoyte Van Hoytema. Through these different collaborations, he, as a director, has carried a few visual techniques across most of his films.

Let’s take a look at 5 of those camera techniques today and break down how he pulls them off.

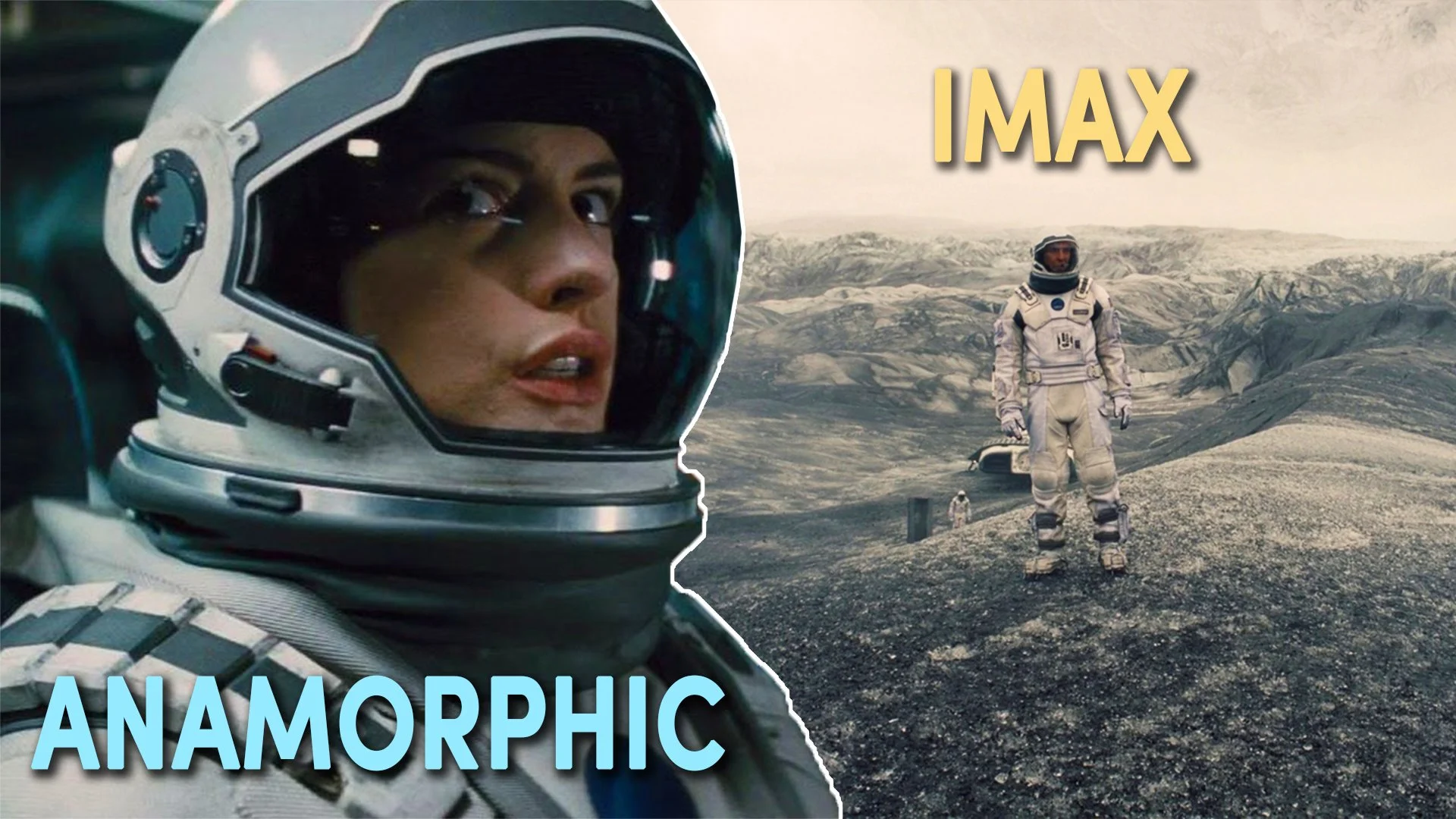

1 - ANAMORPHIC & IMAX

An important creative choice when making a movie is considering what aspect ratio, or dimensions, it should be filmed in. The two most common ratios for cinema are 1.85:1, which is pretty close to the 16:9 ratio which you’d see on YouTube, or 2.40:1 which is more of a widescreen image with black bars on the top and bottom of the frame. Although other ratios, such as 1.33, 1.66 or 2:1 also exist.

Filmmakers will almost always decide on using one aspect ratio for the entirety of the movie.

One trademark of Christopher Nolan’s films is that he often cuts to shots with two different taller or wider aspect ratios during the movie, and even, sometimes, during the same scene.

The reason he does this is because he likes to use the native aspect ratios, without cropping, from the two different camera formats he shoots on. These formats are either the wider anamorphic format, or the taller Imax format.

The anamorphic format uses specially designed lenses, which capture images with a squeezed compression that can later be de-squeezed to arrive at a highly resolved widescreen look.

Imax, on the other hand uses regular spherical lenses, however captures images on gigantic pieces of 65mm film which are 15 perforations wide - providing a taller aspect ratio and wider field of view at an unparalleled resolution quality.

“Our film tries to take you into his experience and Imax, for me, is a portal into a level of immersion that you can’t get from other formats.” - Christopher Nolan

Throughout his career Nolan has favoured wider anamorphic capture, with its oval bokeh, distortion and falloff on the edges of the frame, for capturing more traditional dialogue sequences.

Then he switched to Imax cameras to capture setpieces without dialogue, such as chase sequences, stunts, or aerial establishing shots.

Although Imax was designed to capture vistas and expansive, wide spaces with impeccable resolution, Nolan has also subverted this expectation in his recent work by also using this large format to capture intimate close ups and personal moments: trying to convert nuances in performance into a cinematic spectacle.

2 - ROLLED CAMERA

There are three different ways or axes, to position and move the camera: pan, tilt and roll. A pan - that moves the camera from side to side - and a tilt - that moves the camera up and down - are both very common and can be done with a regular tripod.

The third axis of movement, roll, is however much more unusual and infrequently used.

Usually shots are framed with a level horizon, however sometimes filmmakers decide to rotate the camera on its roll axis. Many times this is done with a 3-axis remote head - a tool that holds the camera and can roll it over and position the camera on its side by an operator who controls it wirelessly.

This remote head can also be attached to a crane or technocrane, if the shot needs to push forward or move around within a space.

He used this remote head and Technocrane setup on Inception but went a step further by even rolling the dream world of the film over on itself. This was done by constructing a set in a soundstage which could be rotated.

3 - ARM CARS & HARD MOUNTS

An aspect of his blockbuster filmmaking that Nolan is well known for are his use of vehicles in big chase or action set pieces.

When filming these sequences he’ll mainly stick to using two camera techniques. Firstly, he’ll lock off the camera in hard mounted shots attached to the vehicle. Or, secondly, he’ll use an arm car or some kind of tracking vehicle to get shots that move on the road with the picture car.

“What I wanted to do was really explore the experience of watching an action film. Try and build this big screen, very immersive experience and find a reason for an audience to watch a car chase again.” - Christopher Nolan

Hard mounts are achieved by rigging the camera directly onto the picture vehicle, whether that be a plane, a car, or a spaceship. This maintains the same frame on a character, letting us view their reactions and get inside their head while the background flies past. These shots can feel quite immersive and real, since, well, they are real.

Audiences are placed directly in the cockpit or driver’s seat and feel all the little, realistic vibrations and reflections as the vehicle moves. These little nuances are part of why Nolan pushes to shoot these stunts practically, rather than using visual effects.

To get wider shots outside which establish the vehicle and action within the world and give a visceral speed to shots, he often uses an arm car. This is a specially equipped, fast driving vehicle, which has a crane arm mounted on its roof to which a remote head is attached with the camera.

Operating this shot requires a few key crew members: one, a stunt driver who drives the car, two, a technician who moves the position of the arm, three, the DP or operator who pans, tilts or rolls the camera's position on the remote head to get the right frame, and four, the 1st AC who rolls the camera, wirelessly adjusts camera settings and controls where the focus is.

4 - KODAK FILM

Unlike most productions nowadays that opt to shoot on digital cinema cameras, Christopher Nolan has a deep love for shooting on film: whether that be 35mm or large format 65mm stock.

“Film, I think, is uniquely suited to pulling an audience into a subjective experience. Film gives you a depth to the image that I find inherently more emotionally powerful and more accessible.” - Christopher Nolan

He favours the way that the emulsion captures colour, or in the case of black and white, how it captures monochromatic hues. He’s used this on movies like Memento and Oppenheimer as a tool to delineate between the different timelines as the movies weave around their nonlinear narratives.

This black and white work has always been captured in different gauges of Eastman Double-X, from 16mm on Following, to 35mm on Memento, and even getting Kodak to specially upsize the film to 65mm for Oppenheimer.

The rest of his colour work he’s captured on Kodak Vision stocks, mainly using 50D or 250D to capture exterior scenes in natural sunlight, and 500T for darker interiors or night scenes.

Although the grain is a large part of the film look, because he normally captures in either anamorphic or Imax (which both have very low visible grain), his movies tend to have a fairly clean look, with the exception being his debut feature which he shot on the more inexpensive but grainier 16mm format.

5 - HANDHELD

A camera technique that Nolan has used in most of his work is handheld. It may have several different practical or emotional purposes depending on the context it's used in, but I’d argue that one of its key uses is as a tool to tell the story from a particular point of view.

“I’m really interested in cinema’s ability to give you different points of view and multiple points of view within a single film. I’ve always really been fascinated by that relationship between the storytelling in movies and how it works and the way it aligns you with different characters.” - Christopher Nolan

Shooting a far off aerial landscape presents the frame and establishes the space from a more detached, objective point of view. Whereas, a subtle handheld camera, shooting over a character’s shoulder, places the audience subjectively right into the shoes of the character.

Even with all the high tech toys he has available, Nolan often decides to shoot handheld in this way: moving in the steps of characters as they do, shooting over their shoulder, or framing up singles on characters with a subtle, organic looseness that aligns the audience with their point of view or places them in the same visceral moment that the character themself is experiencing.